A Explosive Element, Passports, Truck Routes and a Hungarian Success Story

December 16 2024, Volume 5 # 26

A is For Antimony, S is For Shortage

It is something most of us have never heard of or forgotten from high school chemistry. Antimony. Alphabetically it is number five on the list of elements, between aluminum and argon, though related to neither.

We use antimony every day, in batteries, semiconductors in phones and computers. “From electronics to renewable energy, the modern world runs on antimony,” says an article this month in Oilprice.com. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, American Manufacturers use over 50 million pounds of antimony every year. Trouble is, China produces 80% of the stuff.

With tariff threats from Donald Trump, China has already restricted exports.

And along with all that high tech stuff Antinomy is used to make bullets and explosives, to say nothing of the chips for drones and other military paraphenalia. The Pentagon is panic stricken and is looking for other sources. One is Slovakia, another is in West Gore, Nova Scotia. The now closed mine supplied antimony in both World Wars. The company involved says it is working to “unlock future value.” It is one of the only sources of antimony in North America. I think it is a safe bet that if they get the mine running there will be no tariffs on antimony from Nova Scotia.

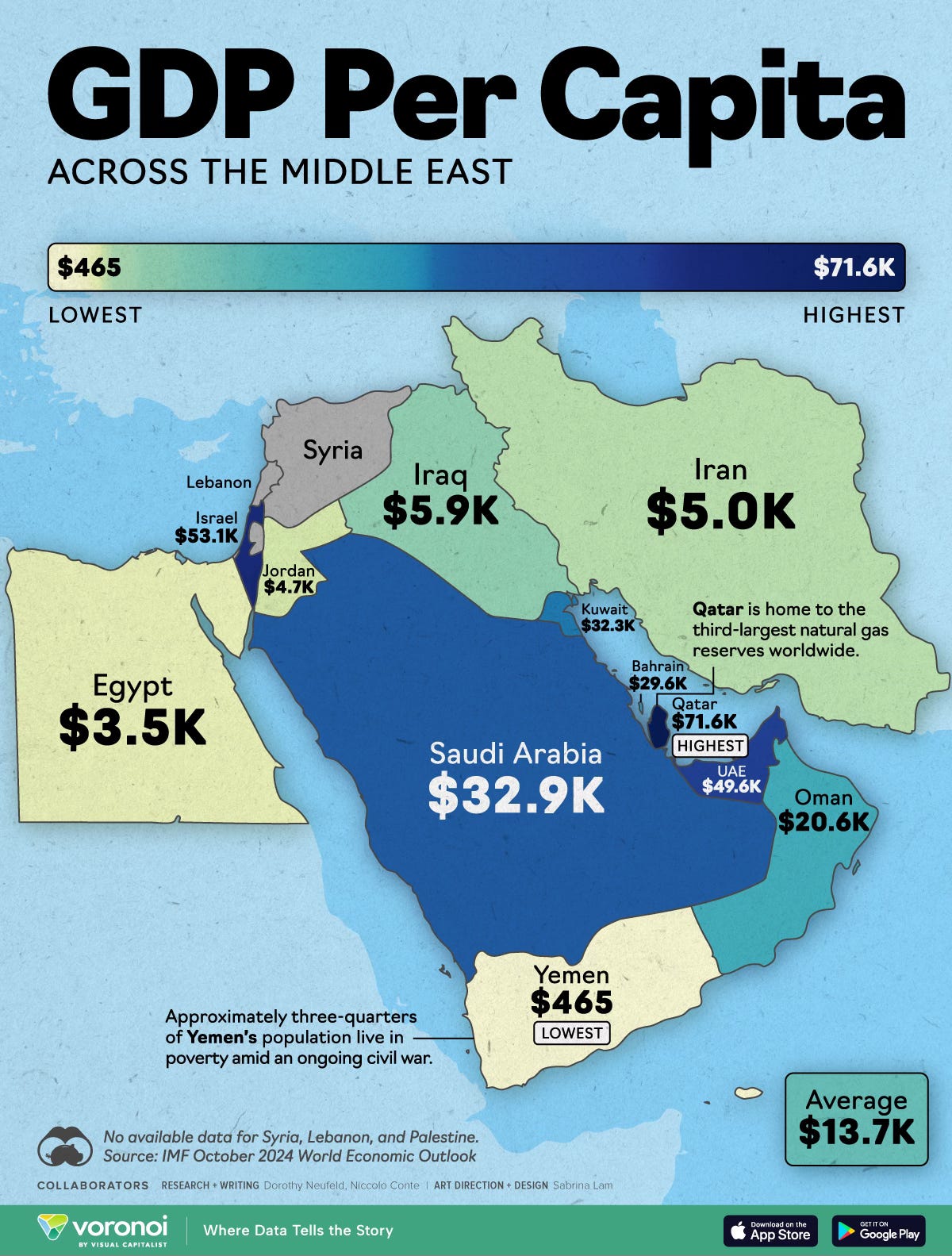

Rich Gulf, Poor Gulf

Qatar is the richest of the Gulf states and the richest place in the Middle East, thanks to huge natural gas reserves on its tiny patch of the Earth.

It spends its money on spectacular buildings and things like the 2022 World Cup.

The business of poor Yemen is war. A proxy war fought for Iran and Saudi Arabia.

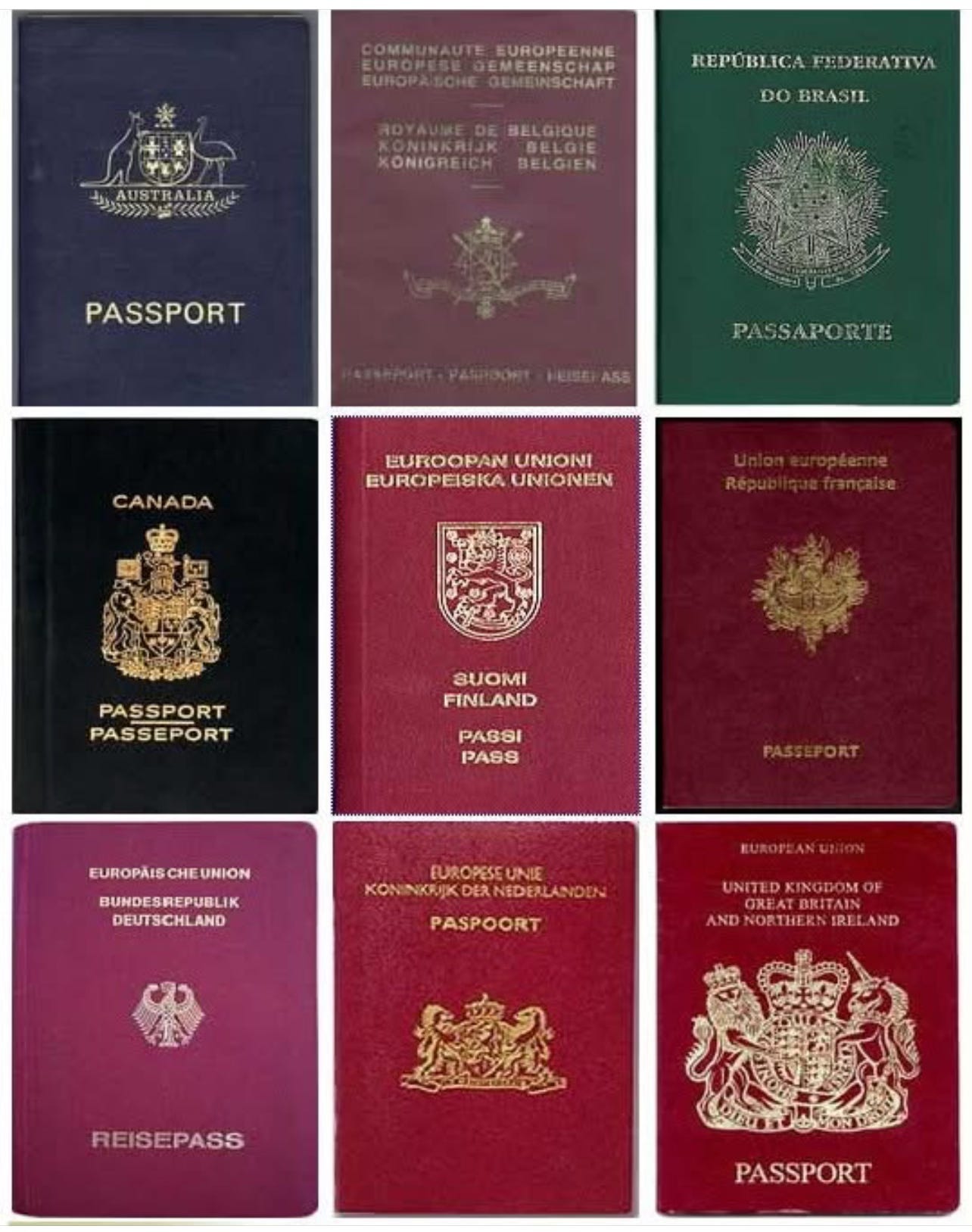

Powerful Passports

They are passports from selected countries from the European Union, Australia, Canada and the United Kingdom and Japan, not pictured here. The list is compiled by Henley & Partners, who I had never heard of until some algorithm sent this info my way. The top passports — Japan, Singapore, France, Germany, Italy and Spain— allow travel without visas to 194 locations out of 227 `global locales’. Canada, South Korea and the passport pictured below are just a few visas shy of the top.

The United States, let’s face it probably the most coveted passport, is down the list with non visa travel to 188 locations. Ten years ago the US was number one.

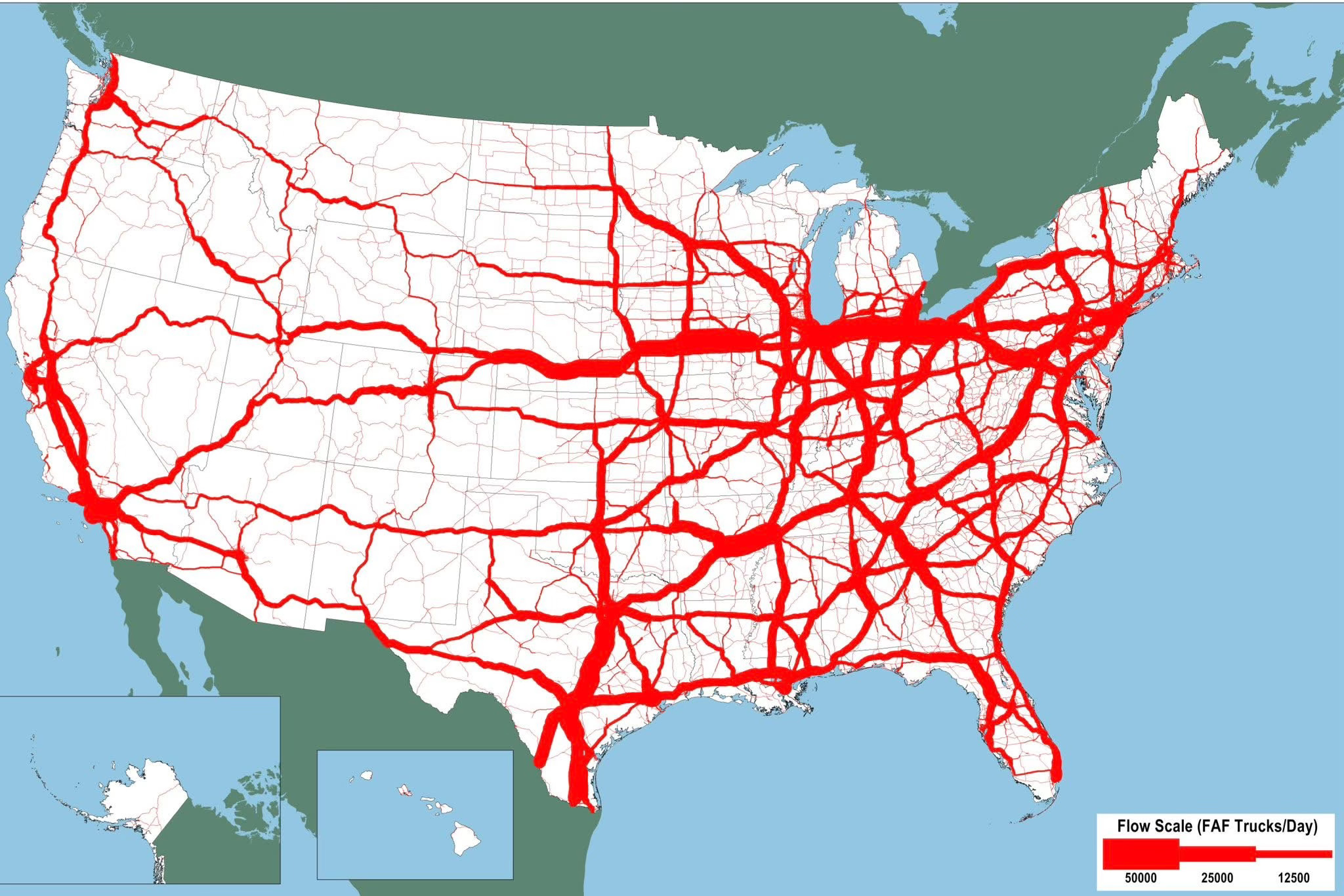

One Day’s Truck Traffic in the USA

The thicker the red line the more truck traffic. An easy way to see how the economies of Canada, the United States and Mexico are linked by the US Interstate Highway system.

The heaviest traffic into and out of Mexico is north of the big manufacturing areas around Monterrey. The thickest red line going into Canada is at the Detroit-Windsor crossing, and then near Niagara Falls, both heading into the densest manufacturing areas of Canada, auto assembly plants and the factories that feed them.

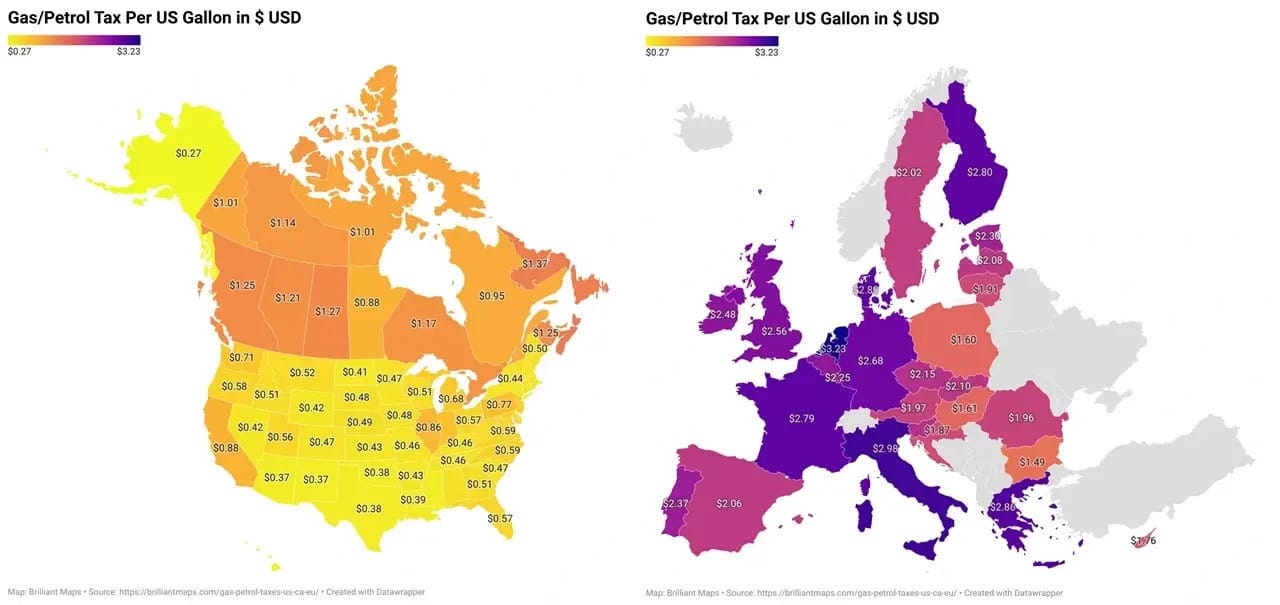

A Mirror Image of European Cities

If Moscow were in the middle of Manitoba it would be colder than Ottawa, which is said to be the coldest capital in the world. The temperature in Edmonton, Alberta, was -9 on Sunday; in its mirror city Hamburg it was +9.

Mirror Gasoline/ Petrol Taxes

In the United States a rise in gasoline prices can bring down a government. In Canada the carbon tax could be the biggest issue in the next election. In Europe taxes are high to discourage driving.

But They Drive Anyway

I think it’s called Elasticity of Demand, or who cares about prices, I want my car.

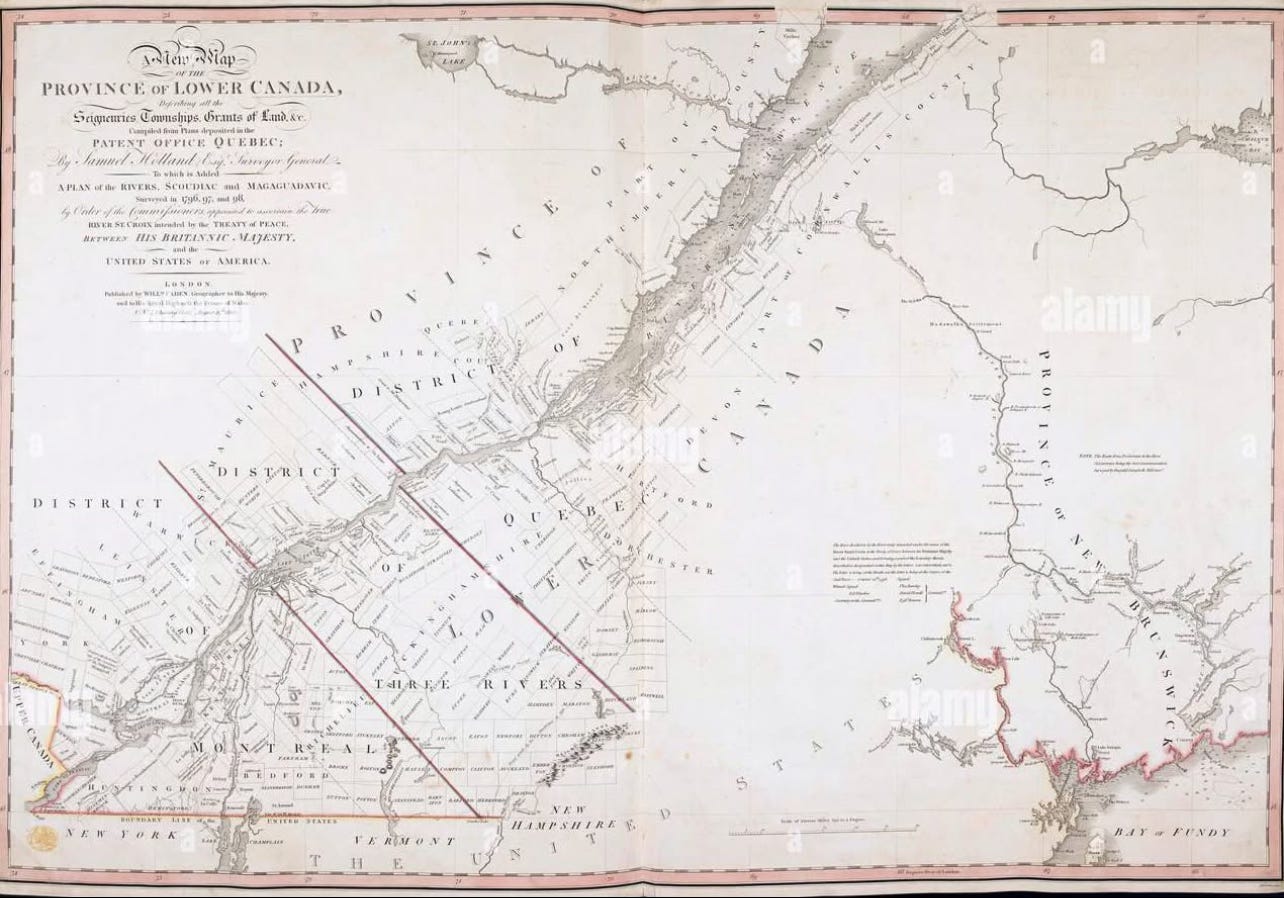

A Map For My Tribe

A map from around 1800. A local will spot names that still exist. Land settled by the French is measured in arpents, and still is in some cases; British and American settlers used acres. Arpent is the measure of land used in France and its colonies before the 1789 Revolution. It is about .91 of an acre. A land surveyor in Quebec is still known as an Arpenteur-géomètre, a beautiful phrase.

Essay of the Week

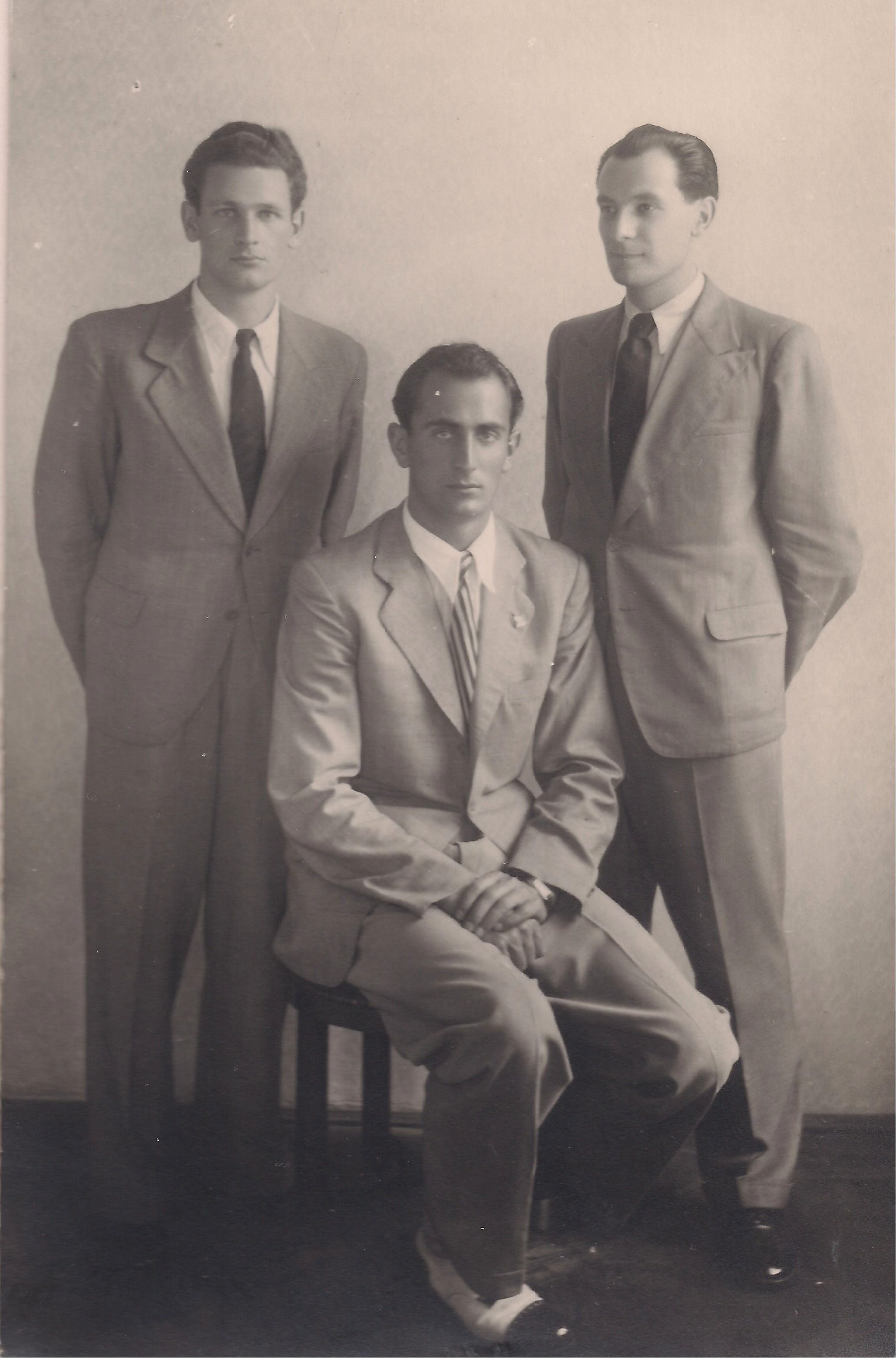

Not only did I write this man’s obituary, I wrote his biography.

***

George Lengvari arrived in Canada in 1951 as a penniless Hungarian immigrant and went on to become one of Canada’s most successful life insurance brokers. It was a profession he came to relatively late in life, starting when he was almost 40 after spending the post war years in refugee camps in Europe and in menial jobs first in Britain and then in Canada.

The wars of the 20th century shaped George Lengvari’s life. His father was killed in the opening months of World War One. George was born five months later in April of 1915, the third of three sons. In an effort to help out a war widow, his uncle adopted his brother Ferenc who took his family name, Csik. That brother, Ferenc Csik, went on to become a national hero in Hungary when he won a surprise gold medal in the 1936 Olympics in Berlin.

All three brothers excelled at school. The oldest brother Akos became a lawyer, Ferenc Csik a medical doctor and George earned a doctorate in political science and law. Mr. Lengvari worked for a bank in Budapest quickly becoming a vice-president. He dealt with lumber trade to Finland, a specialty that helped him during the war when he was moved from the eastern front back to Hungary to help with forestry problems.

George Lengvari was the only brother to survive the war. Akos was killed in Russia and Ferenc died in Hungary in the final months of war where he was serving in a military hospital. George tried to convince his brother to join him in an escape to the American zone in Austria but he chose to stay with the hospital.

The Lengvari family, George, his wife Trude and three year old son George Jr. lived in refugee camps in Austria for three years, moving from the American zone to the British Zone. They worked as translators for the British Army and the British Red Cross and through that connection were able to leave the camps. They moved to Scotland in 1948 where George worked as a gardener and Trude as a housekeeper on a highland estate in Ross and Cromarty.

One of Mr. Lengvari’s duties was taking care of beehives on the estate and he lost himself in his new work. He passed two examinations by the Scottish Beekeepers Association, earning an Expert Bee Master’s Certificate. Later in life the certificate hung on the wall of his office first in Montreal, then in Vancouver.

George decided to move to Canada in the summer of 1951. The Lengvari family, which now included three-month old Christine-- flew on a TransCanada Airlines Northstar, a four engine propeller aircraft that took 12 hours and two stops—one in Ireland, another in Newfoundland—on the trip from London to Montreal.

The family moved into a one-room basement apartment near McGill University. George imagined that with his doctorate there might be some academic work at McGill. There was not.

“They handed me a mop and a pail,” said George many years later. He worked as a janitor for 45 cents an hour, which would be $4.10 an hour in 2012 dollars according to the Bank of Canada’s inflation calculator.

He answered an ad to sell vacuum cleaners door to door and was soon their top salesman, though it was a hard slog with many doors slammed in the face of the immigrant with an odd accent. He was always upbeat and once when he and his wife were out for an after dinner walk in downtown Montreal he looked up at the Sun Life Building, then the tallest in Canada, and said think of how many vacuum cleaners all those people need.

A little later he decided he needed life insurance and walked into the offices of Excelsior Life on St. Catherine Street. It was odd for someone to come in off the street to buy insurance so the manager said, “If you like insurance so much, maybe you’d like to sell it.”

Mr. Lengvari started right away. At first his clients were other Hungarian immigrants, but he soon expanded. His wife Trude managed the business side of things: the paperwork, bookkeeping and chasing down clients for monthly premiums. By 1956 the Lengvari family moved from the series of small apartments they had lived in to a comfortable house in the inner suburb of Montreal West, next door to Sam Etcheverry, quarterback of the Montreal Alouettes and Danny Gallivan, the play by play announcer for the Montreal Canadiens.

Late in 1956 The Soviet Union invaded Hungary and George Lengvari led the Hungarian community’s protests in Montreal. He spoke at rallies in Dominion Square sharing the podium with Mayor Jean Drapeau and federal politicians. As president of the Quebec division of the Canadian-Hungarian Federation, he exchanged telegrams with Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent.

“One result of the sad events of the past few months has been to reveal to the world the mettle of the Hungarian people and I have no doubt but that Canada will greatly profit by the contribution of the new citizens she has warmly received in their hour of need. Yours sincerely, Louis St-Laurent,” read part of Mr. St. Laurent’s second telegram.

Frank Csik, the 16-year-old son of the Olympic champion and Mr. Lengvari’s nephew, was one of the thousands of Hungarians who escaped to the West when the border to Austria was open for a short time during the Hungarian Revolution. He made his way first to Vienna then to a camp in New Jersey. Eventually he contacted his uncle in Montreal and was driven there. Frank Csik moved in with the Lengvari family and was treated as a son.

In November of 1963 Mr. Lengvari started a partnership with Robert Faust, a man he had met at Excelsior Insurance. The two set up an independent insurance brokerage, Lengvari and Faust, and were among the first tenants of Place Ville Marie, by this time the tallest building in Canada.

Mr. Lengvari came up with new insurance products that he pitched to insurance companies. Mr. Lengvari’s big idea, which he continued to modify all this life, was to come up with policies that made life insurance attractive to business executives and in particular owners of family businesses whose concern was saving taxes when passing on wealth to the next generation.

He worked as an independent agent representing many insurance firms but his favourite was Manulife Financial of Toronto. In 1995 Manulife had more than 6,000 agents in 17 countries selling various types of life insurance policies. That year Mr. Lengvari was the top producer for Manulife worldwide.

“Guys like George have more innate entrepreneurial spirit than the average person. You mention George anywhere in the insurance space in Canada and people will know who you are speaking about,” said Dominic D’Alessandro, who was president and CEO of Manulife Financial at the time. “The percentage of people who can make a career in insurance is so low because the failure rate is very, very high. Everyone can survive the first year selling to their aunts and uncles but to sustain a livelihood takes a very special personality, a person who is immensely confident and positive. You are constantly being told ‘no’ and it’s very bruising to the ego.”

In 1995 Mr. Lengvari was 80, an age when most men had been collecting the old age pension for 15 years. That year he took 110 flights, most of them in Canada. A naturally frugal man he flew economy until his son convinced him he could afford to fly business class.

At this stage Mr. Lengvari sold insurance across Canada through referrals from other agents and chartered accountants who had a roster of small and medium sized business clients, many in Western Canada. He kept an apartment in Montreal but increasingly lived in Vancouver.

Mr. Lengvari was a keen athlete. As a young man he and his brothers competed in swim meets across Europe and was a competitive rower. He swam all his life and set a Canadian record in the 200-metre relay when he was 82. In Canada he took up golf and found it a great way to exercise and talk business at the same time. When he was 88 he shot a round of 44 on the front nine at Stowe, Vermont, where his son George and daughter Christine both play.

George Lengvari died at home in Vancouver on March 19. 2012. His wife Trude pre-deceased him. He is survived by his son and daughter and his nephew Frank.