Aluminum, The Dow Jones, The Austro-Hungarian Empire and a Talk Trainer.

March 24, 2025 Volume 5 # 41

Aluminum and Aircraft

Seventy per cent of a Boeing aircraft is made of aluminum. But Boeing says the raw material makes up only two per cent of the total cost of the finished aircraft.

This is the Boeing assembly line in Renton, Washington. So far the company says it is not worried about the 25% tariffs on aluminum. Boeing hedged and stockpiled supplies ahead of President Trump’s announcement, according to Brian West, the Chief Financial Officer and Executive Vice President of Boeing, speaking on March 19. “It is also important to understand that 80% of our commercial spending and over 90% of our defense spending in our supply chain is US-based.”

He did not specify just how much aluminum is `US-based’.

Canada is the main supplier of aluminum to the United States, from smelters in Quebec. and British Columbia. The chart from the Federal Government.

“In 2023, Canada produced an estimated 3.3 million tonnes of primary aluminum. Canada is the world’s fourth-largest primary aluminum producer, following China, India, and Russia. Canadian aluminum producers have the lowest carbon footprint among major producers, thanks largely to their reliance on hydroelectricity and cutting-edge technologies,” says the government website. The United States takes almost all — 3-million tonnes- of Canada’s aluminum production.

Aluminum uses massive amounts of electricity— in Canada’s case hydroelectricity- to convert alumina— which in turn is made from bauxite— into aluminum.

Rio Tinto, which owns the company once known as Alcan, may have to find new markets for its aluminum. Then American customers may have no choice but to buy it anyway and pass the extra costs on to people making cars, planes and soft drink cans.

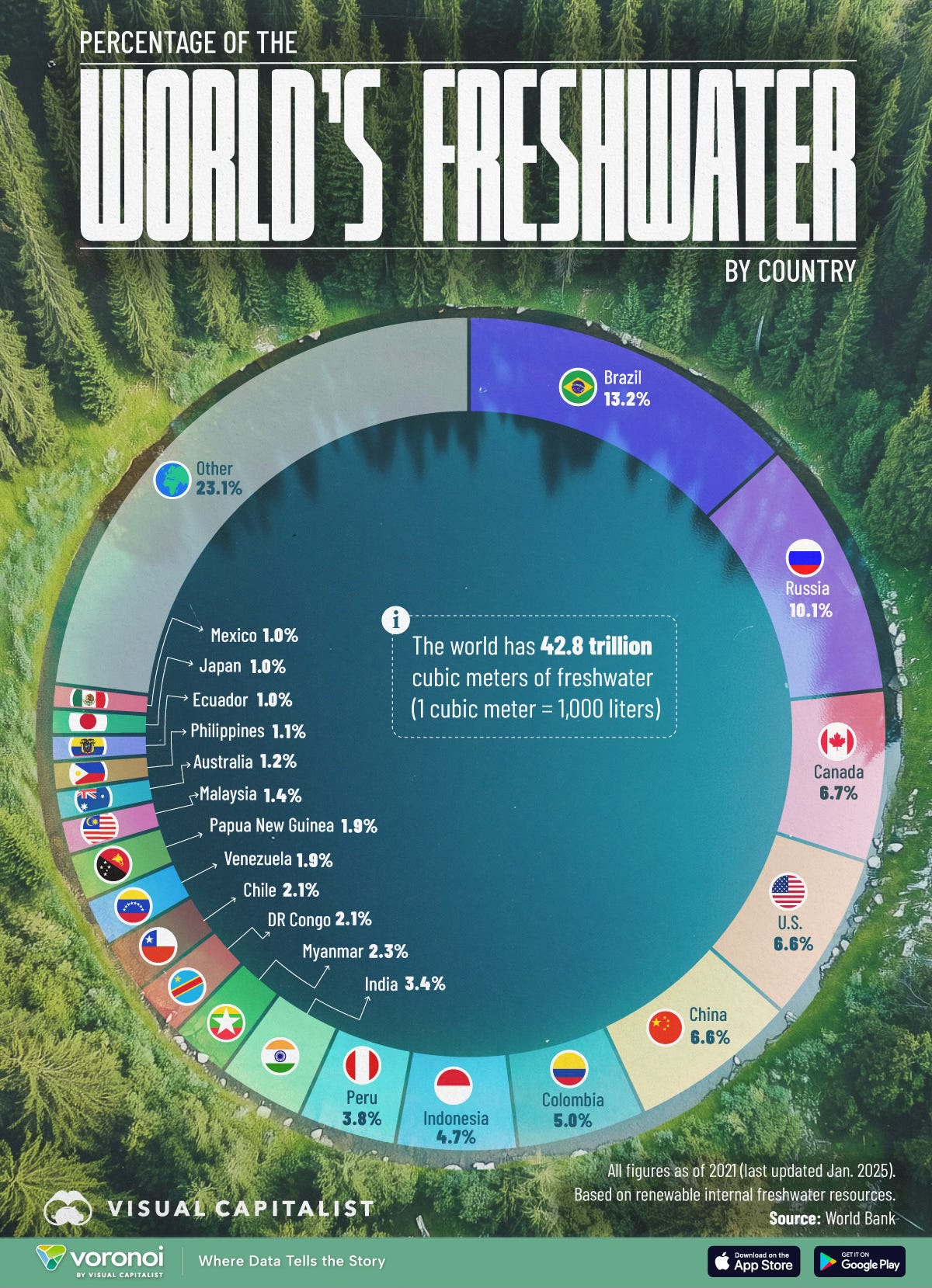

Another Issue: Water

President Trump muses about water from Canada. There is a lot of it.

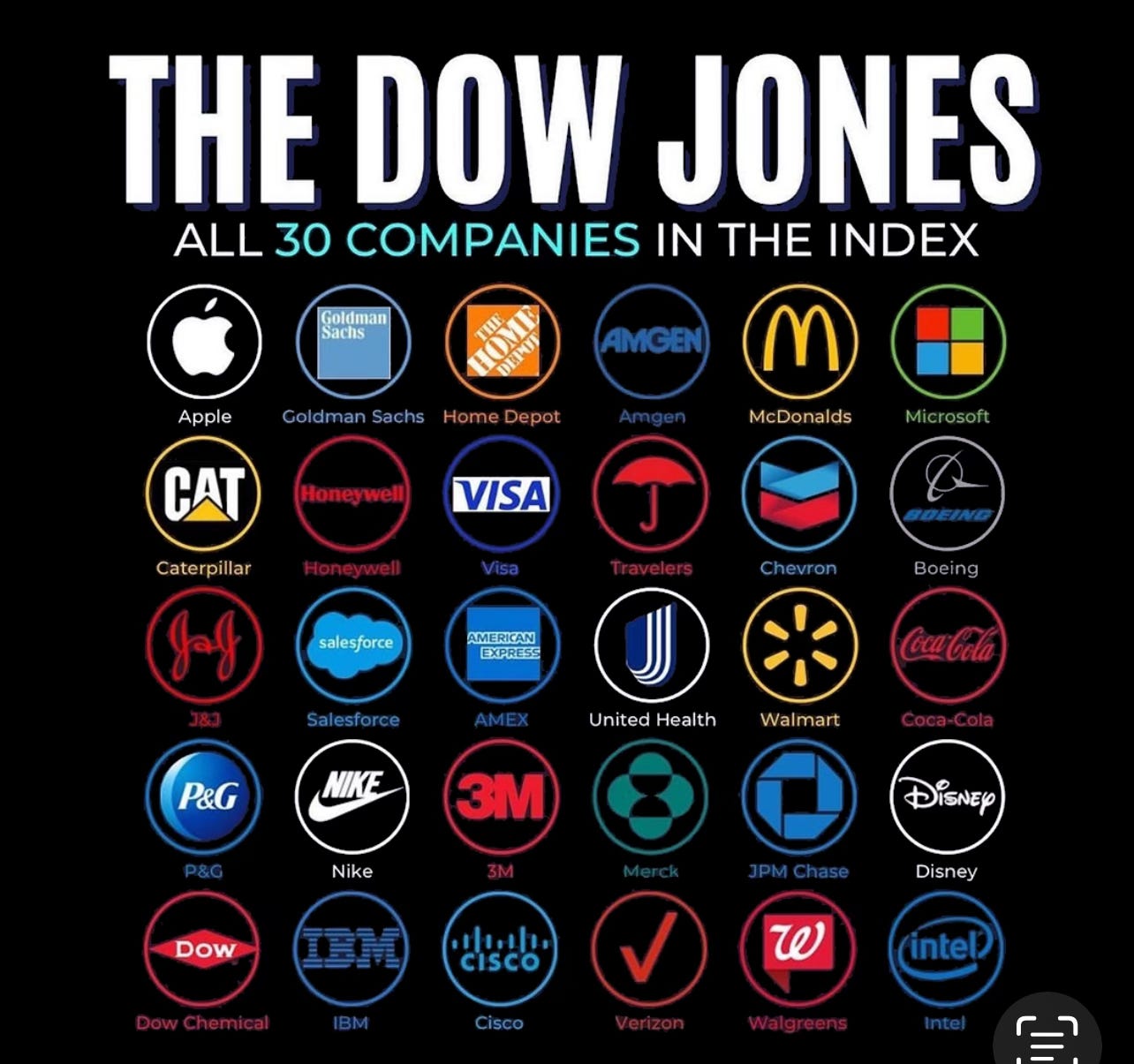

The 30 Names of the Dow Jones Industrial Index

The Dow Jones is the most talked about stock market index, though the S&P 500 is a more accurate reflection of what the market is doing.

The Dow Jones Industrial Index was created in 1986 by Charles Dow who founded the Wall Street Journal with his partner Edward Jones. None of the original companies are on the list today. Big companies come and go. Original names included the American Tobacco Company, United States Rubber Company and General Electric which was only booted off the index in 2018. 3M is the oldest name on the Dow and the sticky note maker has been a Dow stock since 1976. The newest addition is Amazon, which was added in 2024.

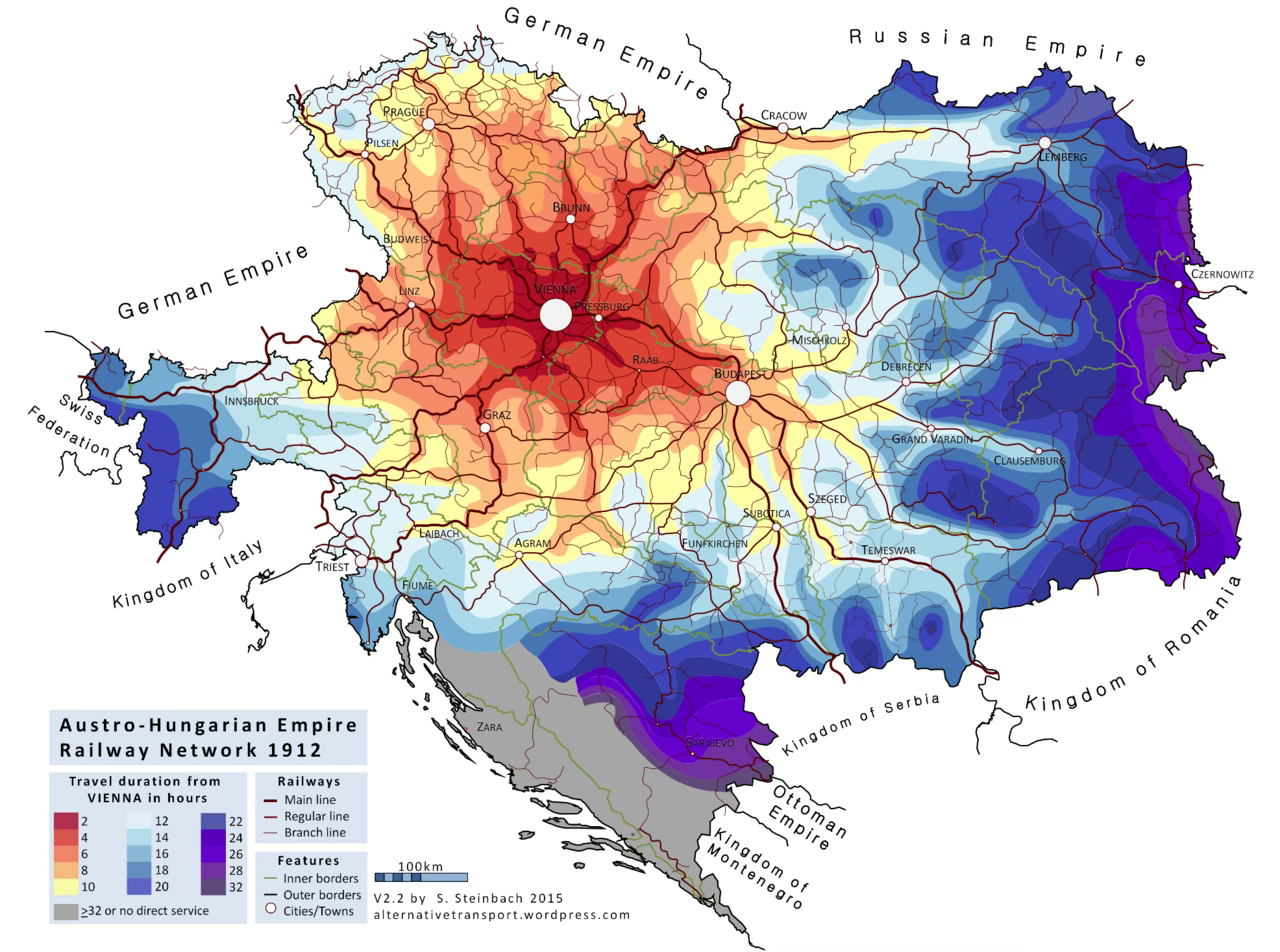

The Forgotten Empire

All railroads lead to Vienna, though some go to Budapest first.

The railway network of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, two years before the assassination of the Archduke Ferdinand and his wife in Sarajevo, the incident that sparked the Great War. Austro-Hungary would not exist by the end of the war, and neither would the other empires that surrounded it, the Ottoman Empire, the German Empire, the Russsian Empire, and kingdoms of Serbia and Montenegro.

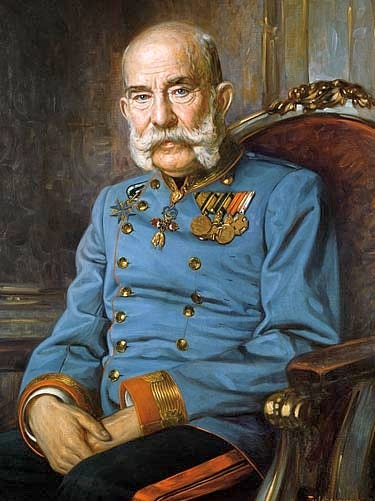

Emperor Franz Joseph ruled from 1848 until his death in 1916.

Here is what the Austro-Hungarian Empire looks like today, divided into ten countries, many of which didn’t exist in 1914.

Austria, and especially Hungary, were the big territorial losers of the First World War, Romania taking a huge slice of Hungary. That came from the Treaty of Trianon, a subset of the Treaty of Versailles. Its anniversary is like a day of mourning in Hungary.

Queen Marie of Romania, a grandaughter of Queen Victoria, and raised in England worked the room at the Paris talks.

She convinced the likes of Presidents Wilson of the the USA and Clemenceau of France that Romania faced a violent Bolshevik revolution unless it was given Transylvania, Besserabia and other territories. She won, Hungary lost.

The Tower of Babel

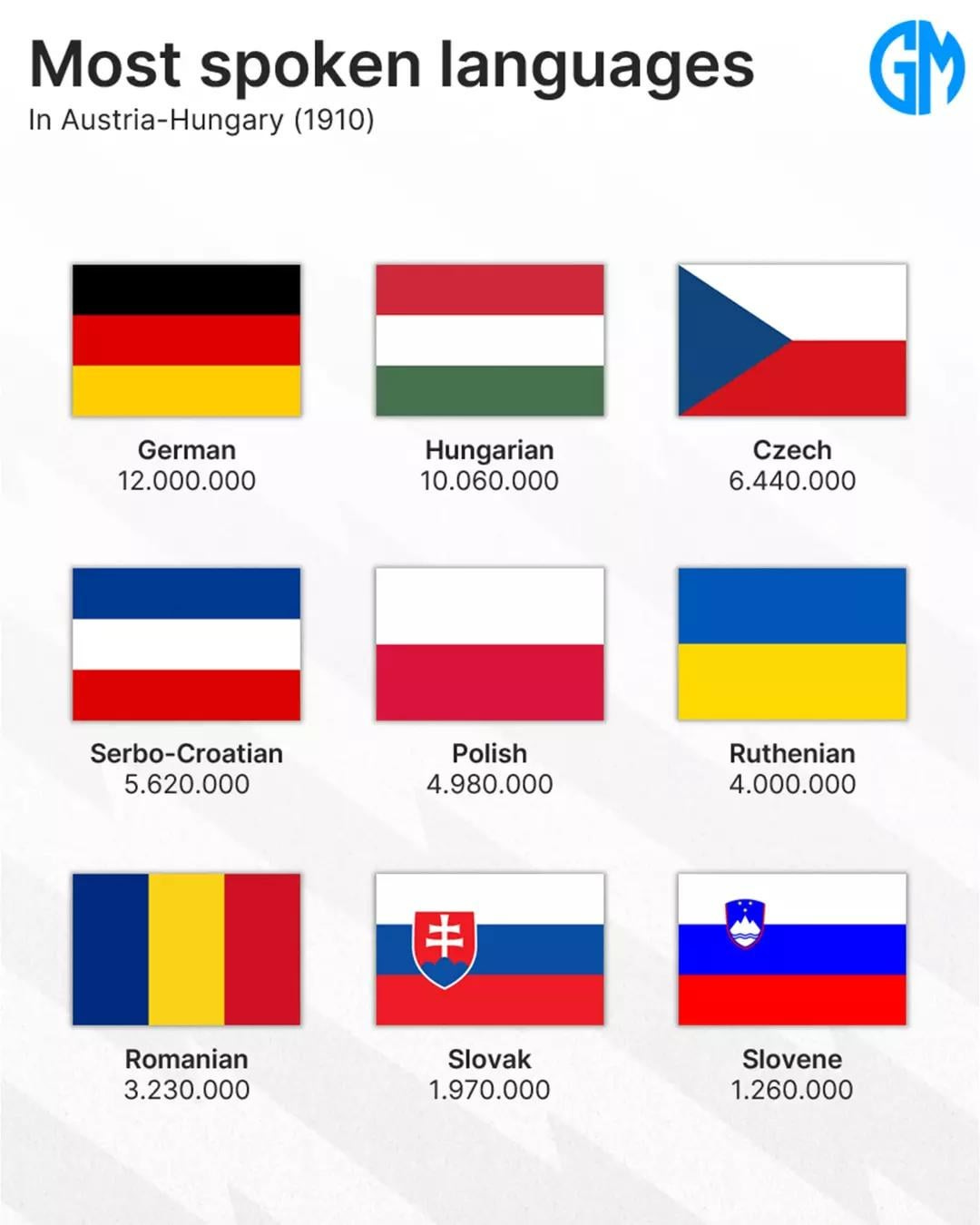

There were at least 23 languages spoken in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, from Italian to Yiddish. Speaking of Italian, a large slice of Austria was ceded to Italy.

Essay of the Week

A Man of the Spoken Word.

David Candow trained thousands of radio reporters and announcers in eight countries how to sound more natural on the air. His formula was simple enough: speak on radio the same way you would in a conversation and keep your sentences short and to the point.

He started working with announcers and program hosts at the CBC. For many years one of his courses was often the first thing a new hire would go through.

Shelagh Rogers said when she started at the CBC in 1980 one of the first things she did was attend a course given by three people. One of them, Gloria Bishop, who went on to be her producer at Morningside, suggested she might do better as a researcher than an announcer. David Candow was kinder.

“He told me to stop trying to sound like Barbara Frum (the host of As it Happens at the time). He put an arm around my shoulder and said: “Look, what I’m telling you is just be yourself. You don’t have to sound like everyone else or anyone else.”

David Winston Candow was born in the small town of Curling just outside Corner Brook Newfoundland in July of 1940. He was the ninth, and last, child of James and Annie Candow and was 20 years younger than his oldest sibling. Two of his brothers went off to war and he didn’t meet them until he was six years old. David’s middle name was in honour of Winston Churchill, the British wartime prime minister.

His father joined the U.S. Army corps of Engineers during the First World War, building timber bridges in the Pacific Northwest. In 1928 he started working as a master carpenter at Bowater’s paper mill at Corner Brook and worked there until his retirement at 65 in 1957.

“Our father worked in Argentia during World War Two in the 1940's building the U.S. Naval Base,” said Mr. Candow’s older sister Dorothy.

David grew up in the house his father built and went to high school in Corner Brook and then to Memorial University in St. John’s. He stumbled into broadcasting because of his hobby, performing in amateur theatre productions. The regional director of the CBC at the time was also chairman of the local drama society. He was looking for an assistant program organizer for the Schools and Youth department and Mr. Candow fit the bill. That was 1964 and David Candow would work at the CBC for more than 30 years.

When David Candow started at the CBC there was a style guide that gave those types of hints about how to write for broadcast and how to speak on air. There were certain sentences that read like chalk scratching on a blackboard. “Harry and Mary went to Barrie in a car,” was not to be said on air as “Herrie and Merry went to Berry in a kar.”

Chief announcers weren’t always right, but they did try to correct such clangers as `pitcher’ for picture, and `meer’ for mirror. David Candow taught more subtle skills, the art of being yourself on radio.

For a man who taught on air performance, David Candow never worked on air. But he knew how he wanted the program he produced to sound. Scripts should be written in short declarative sentences; words should be spoken as they are in real life conversations. Here are some of his guidelines for broadcasters:

Write for the ear, not the page.

You’re not an actor. Try to improve on the real you.

Forget the audience might be millions, imagine you’re speaking to a

friend.

Use plain words; avoid long pretentious words that appear in print and never in conversation.

Mr. Candow first took up training part time while he worked as a producer and program executive in CBC Radio in various parts of the country, finally settling in Toronto. In the mid 80s he took up training full time. The CBC had relationships with other broadcasters and he taught broadcast skills to the English language service of Dutch and German radio.

“He went to South Africa just before Nelson Mandela was released,” recalled his wife Catharine Haynes. “His job was to teach them how to broadcast in a post apartheid world.”

He also worked training broadcasters in Indonesia and Malawi, one of the poorest countries in Africa. But it was after he retired from the CBC that picked up one of his biggest training assignments at National Public Radio in the United States.

Jeffrey Dvorkin, who had run CBC Radio News, was hired as vice-president of News at National Public Radio in 1997. He was surprised that there was no training program to polish the skills of the hosts, reporters and writers on the national NPR network. He knew David Candow had left the CBC and he decided to bring him down to Washington.

“There was a lot of resistance. The announcers were nervous and insulted. Some hosts were furious. Like a lot of on air people they thought that everything that came out of their mouths was golden,” said Mr. Dvorkin, who now teaches journalism at the University of Toronto, Scarborough.

David Candow knew he was entering an ego charged atmosphere when he arrived at NPR’s offices in Washington. He had seen it all before at CBC training sessions across Canada. It took him just a morning to win over almost all of the on air staff he met.

“One of them came out and said `Why didn’t you tell us he was so brilliant?’” remembered Mr. Dvorkin.

David Candow’s nickname at NPR was the Host Whisperer. It described what the Canadian broadcaster did: train the on-air hosts to speak and write in plain, conversational English. Linda Wertheimer, co-host of All Things Considered, gave him the name Host Whisperer. She admitted she and her fellow host, Bob Edwards, were irked at being sent to training school.

“We were very annoyed that anyone would think we were not perfect,” said Ms Wertheimer from NPR’s studio in Washington. “The people David really helped were those making the transition from radio reporters working in the field to being on air hosts.”

She pointed out the technique for a long radio interview is much different from looking for clips for a short news item.

David Candow spoke with the Newfoundland accent of his birth. He had nothing against accents, as long as the speech was natural. When the Washington Post wrote a piece about him in 2008, the writer mistook his Newfoundland accent for what he described as “ the blunt working-class Canadian accent,, with its elongated and flattened o’s, and d’s that stand in for `th’ (“dare” for “there”).” Obviously a man who had never visited Newfoundland.

It was in his post retirement period that he picked up one of the oddest assignments. The BBC asked him to go to the United States to train one of its broadcasters stationed there. That was the eighth national broadcaster on his list.

David Candow was born on July 17, 1940. He died of a massive heart attack on September 18, 2014. He was scheduled to do a training session in Washington DC in late September, helping a bright political journalist who was starting in an air job on National Public Radio.