Cheap Canadian Oil, Royal Warrants, A Digital Busker, and Bill Marshall DFC Continued.

January 27, 2025 Volume 5 # 32

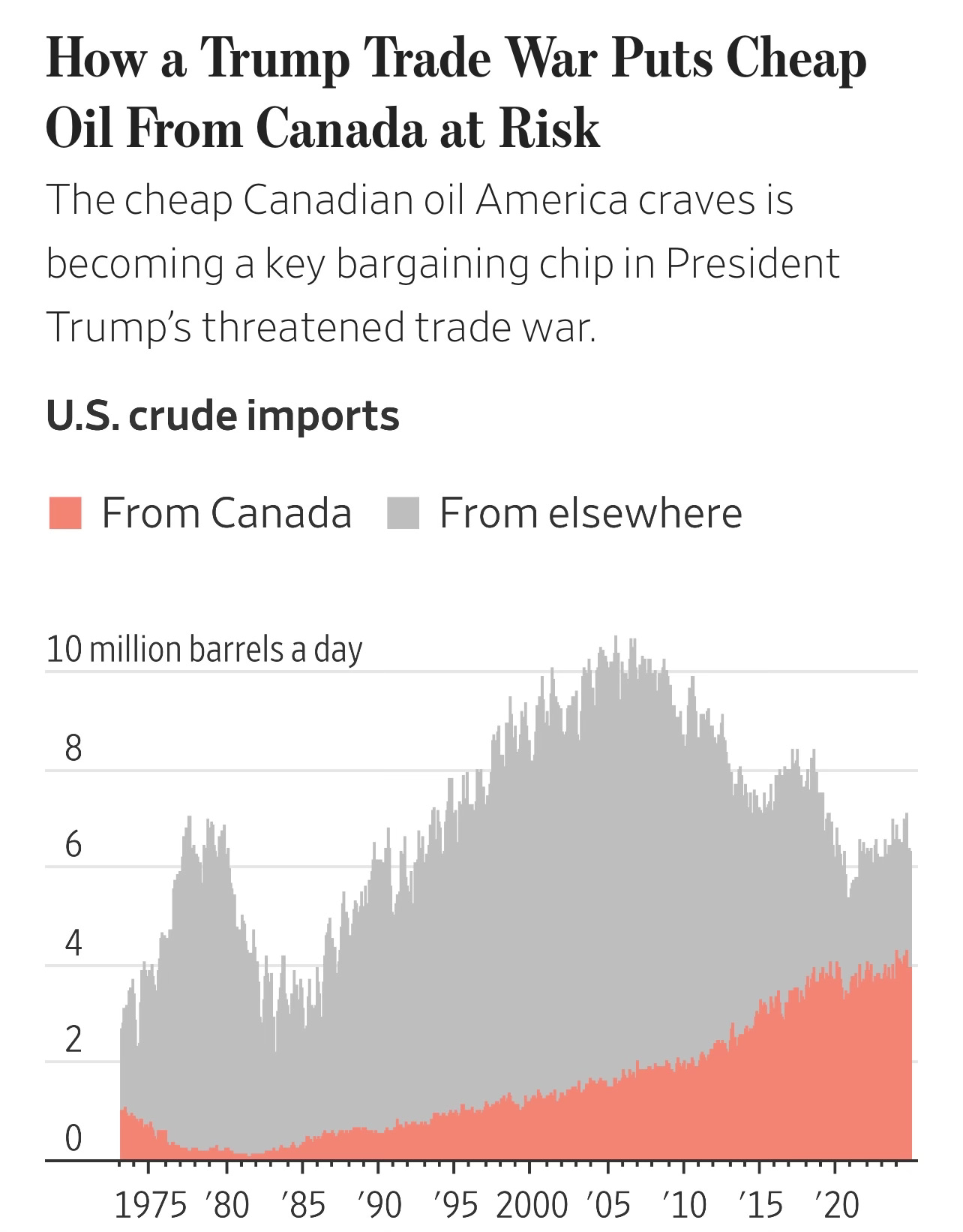

The Wall Street Journal States the Obvious

From Wednesday’s paper.

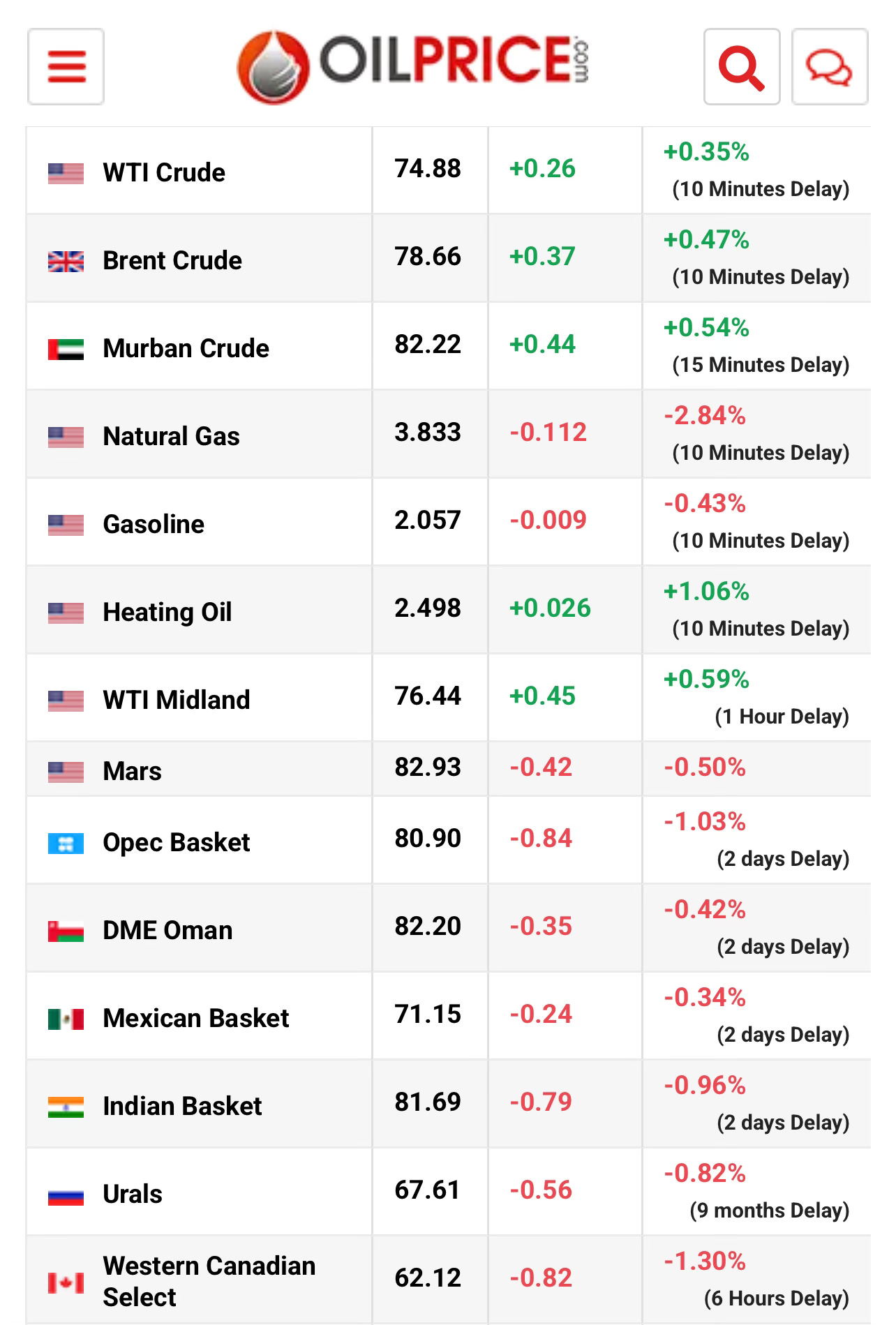

Proof that Canadian Oil is a Bargain

From Friday. WTI is US$74.88; Western Canadian Select is US$62.12

One of the big reasons is that Canada needs more pipelines to ship its oil to foreign markets. RIght now 97% of Canadian oil exports goes to the United States so the price is knocked down. High level political Nimbyism blocks pipeline expansion for oil and natural gas. Prime Minister Trudeau told the German Chancellor that there is “no business case” for natural gas; Quebec blocked a pipeline from the west to the Atlantic where it could be shipped to other markets, cutting reliance on the US.

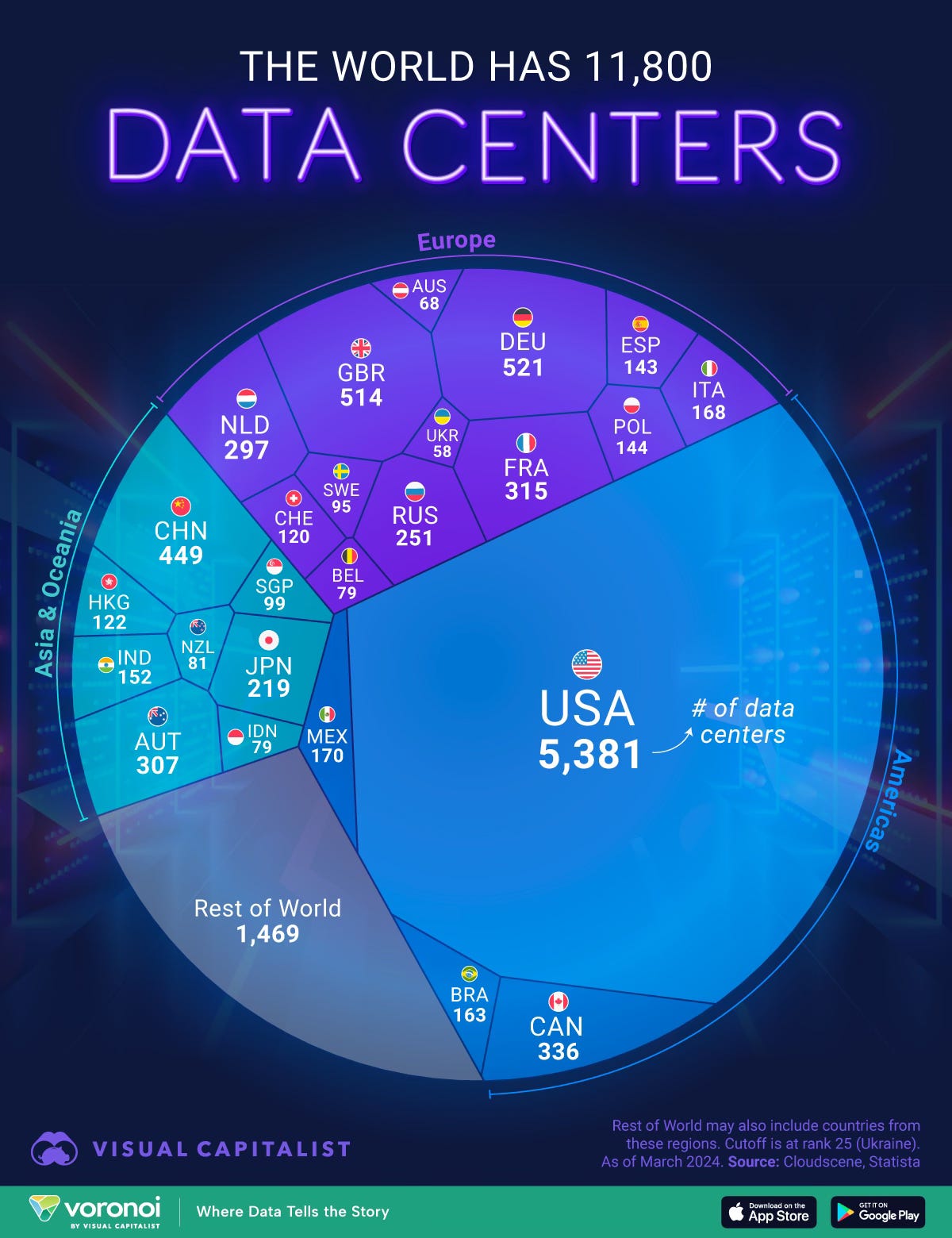

Data is the New Oil

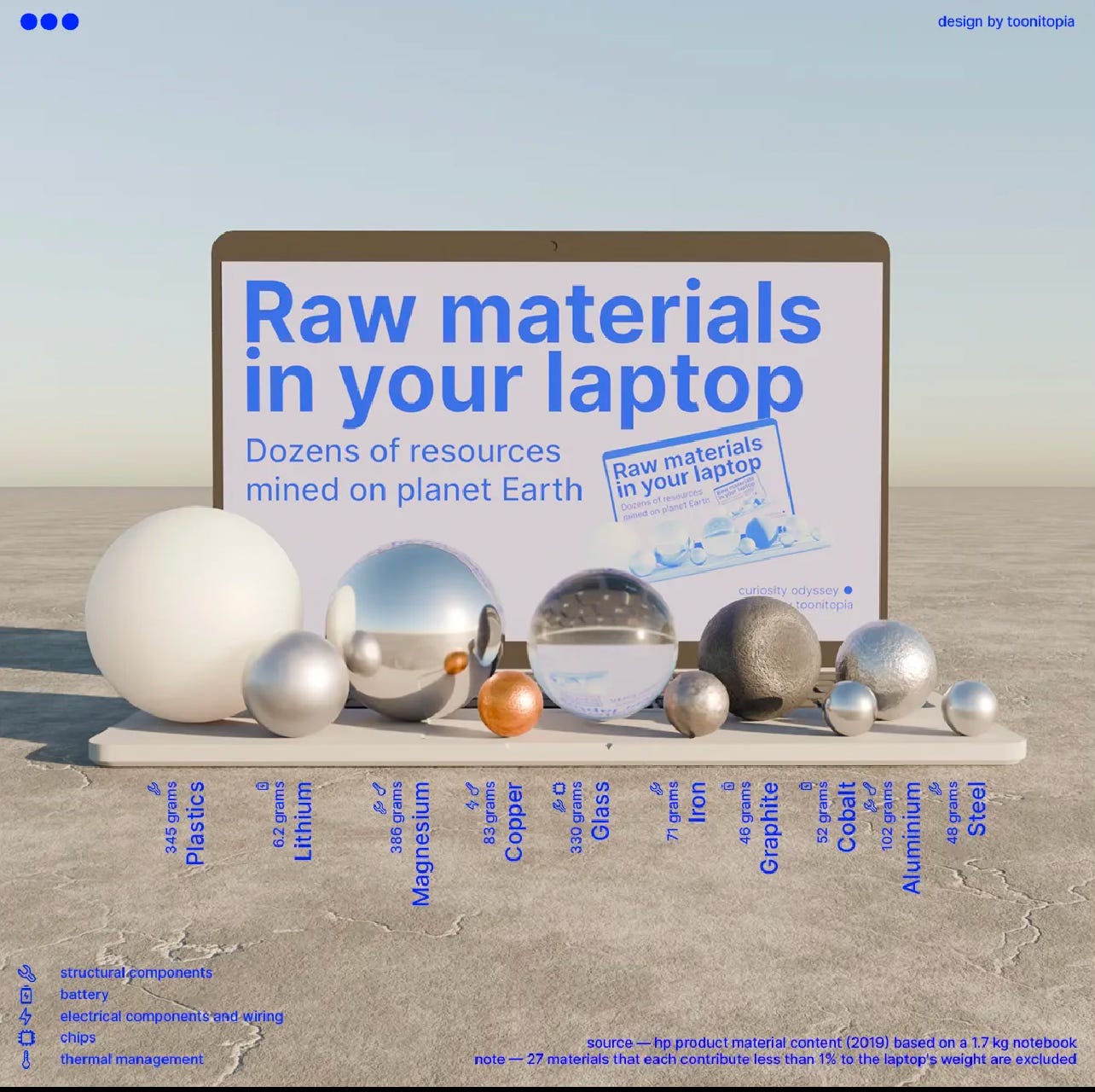

Laptop Guilt

And much of the same stuff goes into Cell Phones.

The World Map Drawn by Flight Routes

Napoleon at His Peak

The Emperor controlled more of Europe than Hitler did. He had the same nemesis: Britain, an island 20 miles from Calais that he couldn’t conquer. And he was about to make the same mistake as Hitler: Invade Russia. Unlike Hitler, Napoleon occupied Moscow. But the Russians left him nothing. His mighty army was destroyed on the way back to Poland.

The map is 1812. On October 15, 1815, Napoleon landed at Saint Helena, forever.

No News like Old News

I was looking for an old article of mine, and couldn’t find it, when I came across this. A piece on Royal Warrants I wrote for the Christian Science Monitor, the politest people I ever worked for. I was their Canadian stringer for about 20 years from the early 1980s, and filed occasional stories from elsewhere, in this case London. I did this story on Royal Warrants first for the CBC, then re-worked it for The Monitor. Where else but England could you find someone named Miss Pickles.

The story is as printed, but I added the image. And it was before the Royal Family removed all its Warrants, four I think, from Harrods because of the creepy owner and his libelous contents, and long before his sex scandal.

Marketing With a Royal Touch

Centuries-old tradition honors products, from bagpipes to cars, bought by royal family

By Fred Langan, Special to The Christian Science Monitor

November 6, 1991

LONDON

'BY Appointment to Her Majesty the Queen."The words and the accompanying royal seal constitute the Royal Warrant, which can be seen on everything from a package of tea to the exterior of high-priced shops in London. The Royal Warrant is about selling using the old-fashioned appeal of snobbery and exclusivity. And British merchants hope it gives them an edge. "I'm not sure if snob is the right word, but I can understand why people might use it," says Gerald Hamilton, managing director of Fortnum and Mason. "It sets you in the top part of the market." Fortnum and Mason supplies groceries to the Queen and leather goods to the Queen Mother. Over the door of the store on Picadilly is a huge royal coat of arms, boasting of the status of being a place where the "royals" shop. Royal Warrants are awarded to tradesmen who serve the royal household. This is an ancient practice that means little at home but is helpful in selling abroad - to Americans, Europeans, and especially the Japanese. "British people are very price-conscious, they all want to shop at Marks and Spencers [a low-cost British department store], rather than at a Royal Warrant holders where they might pay a bit more for the same product," says Commander Hugh Faulkner of the Royal Warrant Holders Association. Four members of the royal family can grant Royal Warrants: the Queen, the Queen Mother, the Duke of Edinburgh, and the Prince of Wales. In the past other family members, such as a Princess of Wales in the 19th century, were allowed to grant warrants. Harrods, a large London department store, is one of only 11 firms which has all four Royal Warrants. Other firms include Rolls Royce and the Rover Group, makers of Land Rovers and Range Rovers, driven by all members of the Royal family. Warrants come in some unexpected areas. John Weatherston of Glasgow holds the warrant as maker of the Queen's bagpipes. Valerie Bennet-Levy, one of only 40 women warrant-holders out of a total of 890, makes flower bouquets for the Queen. Mayfair Window Cleaning Company washes windows for the Queen Mother. There is little doubt among those who hold the warrant that it is a valuable marketing tool. "When Americans want something English, as a present say, and they see it's got a Royal Warrant, it's a valuable selling point," says Sheila Pickles, managing director of Penhaligon's Ltd., a perfume and toiletry maker with warrants to supply both Prince Philip and Prince Charles.

Miss Pickles says the whole thing is especially English. "I suppose we're a race of snobs," she says half-jokingly. But she is a clever businesswoman who has taken Penhaligon's from near bankruptcy to success over the past 15 years. Two Royal Warrants helped her do the job. Royal Warrants have been around since the 12th century, but they really took off as a business tool in the 19th century when Queen Victoria and her pro-industry husband, Prince Albert, granted hundreds of warrants. Getting a Royal Warrant is not easy. A company must supply services to the royal family for at least three years. Keeping one is usually easier, though some do drop off the list. George Trumper, a barber shop near Buckingham Palace, used to cut the royal hair, and be able to boast of it in its window. No more. And Commander Faulkner, a retired Royal Navy officer, has spent 11 years keeping a careful eye on those who break the rules. He gives the example of a Welsh taxi driver who, after taking a few fares to Buckingham Palace, decided to give himself a Royal Warrant and put it on his business cards. Not done. "He was fined British pounds 500," reports Commander Faulkner. Some loyal Englishmen are dismayed that many warrant-holders are not British. Rupert Murdoch - an Australian turned American - owns Hatchard's bookshop, which has four Royal Warrants; Penhaligon's is owned by The Limited of Columbus, Ohio; Fortnum and Mason's is owned by the Canadian Weston family; and even venerable Harrods was bought six years ago by the Egyptian Fayed brothers. There could be changes in the ancient world of Royal Warrants. Some warrant-holders worry that when Charles, the environmental Prince, becomes king, there could be new "green" criteria to win the status symbol. The royal grocer may have to worry more about dolphin-safe tuna than carrying only the best in caviar.

The Digital Busker

I almost never carry any cash. That means I can’t give money to people asking for it. The other day I gave $20 to a nice man who sits across the street from my favouritie coffee shop. I used to drop a $2 coin if I liked the music in the subway. But this busker is hyper-modern. He has a link where you can send money to his account. Smart.

Essay of the Week

The Next chapter in the life of Bill Marshall DFC. He has given up the rough job on a whaling ship and is on a train heading to Johannesburg.

The Wheels of Fortune

Huge mounds of white earth, packed in the shape of a pyramid appeared outside the window of Bill Marshall’s carriage. The steward had put his bed away and after twenty-nine hours on the train he was anxious to get into one of the richest cities in the world and get to work.

The mounds were tailings from the world’s richest goldfields, what was left over after the crushers and sifters prepared the gold ore for its chemical bath. Off a bit farther he could see the smoke stacks of the refineries and the wheels above the mines.

‘Every day those mines bring up 100,000 tons of rock to be crushed into powder, some of it brought up from 8,500 feet below the surface. That’s half a mile below sea level,” the Afrikaner had told him over a late night whiskey. “And every year we turn out 420 tons of gold and 11 tons of silver.”

As he got off the train, Bill looked over and there were now more guards crowded around the van. They were taking off some lightweight packages—he figured it must be cash to pay the workers—and loading on heavy wooden crates, which he assumed must be filled with ingots.

He had already changed into causal clothes and headed for a rank of taxis. From the Johannesburg Star he had the address of what looked like a respectable rooming house. And he was going to need some transport. This city was spread out a bit, and he didn’t want to rely on public transport.

After settling his two cases in his room—he paid for two weeks in advance—he asked his landlady directions for the high street, where he could find a bank and a post office. He opened a bank account and then went to the post office to call another number listed in the paper.

“Where are you,” the man asked on the other end. Bill told him.

“Stand outside, I’ll be round in 15 minutes.”

True to his word, the man arrived in a quarter of an hour. And ten minutes later Bill was the owner of BSA 250, cheap reliable transportation. He drove the owner home and then followed the Afrikaner’s instructions to the mine most likely to hire a former sailor.

It was the Crown Mine, the closest in to the city, just near the southern working class suburbs where the train had traveled that morning. Marshall had no trouble following directions. As he approached the mine site he could see the giant wheel whirring above the mine site, miles of wire and cable doing the work of hauling the ore up and sending the men down.

How it was all done he wasn’t quite sure yet. There was a sign in English and Afrikaans that said office, and that’s where he went.

“How can I help you,” said a man behind a wooden desk covered in what looked like plans, blue papers with lines on them. The man spoke with a thick South African accent, thicker then the sailors from Cape Town.

“I’m looking for work.”

“Well I guessed that, man. What can you do?”

“Run a winch, take it apart and put it back together again. And I know cables, wires and cranes. I was a lamplighter on a freighter called the Harmattan and I worked on a whaler where I was in charge of the gear. I reckon I could do the same here.”

Halfway through that spiel the man looked up. He had the leathery face of white man who’s spent too long in the hot sun. Marshall had seen the type in Australia.

“Well you’re in luck my boy. We need someone to work on the gear here. You’ll work under Martin Cooper. He’s about to retire, go back to the Cape and grow wine. If you learn fast enough you can have his job.”

Marshall stood there and didn’t say a thing. He wasn’t negotiating, just dumbfounded to get the work so fast. But the boss man must have thought he was playing tough.

“Alright. Eight hundred a month. But no more. Here put you name down there, if you can write, and sign on. What is you name, man?”

“Marshall. Bill Marshall.”

“Alright Marshall. Sign up and get to work. We’re mining gold here not running some ship.”

There was an army of workers pulling gold from the ground, 25,000 white men and 200,000 natives according to the Afrikaner. From what Bill gathered there was a preferential hiring system and the white men got the easier jobs, or at least the better paying ones.

Eight hundred a month. Phenomenal pay, considering he’d just made 700 for the most wretched six months in his life. He might like it here.

Life took off for Marshall. The work was simple enough. He had to make sure the cables were safe, always on the look out for work wire. Most of the work was above ground. It fascinated him that this mine went down a little more than a mile.

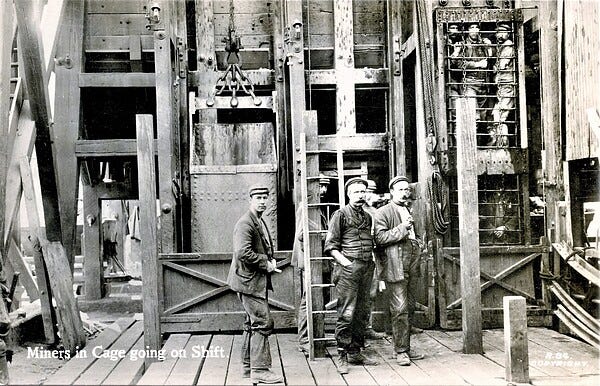

The cage, he found out in a hurry was the metal room that hurtled up and down the mine shaft, stopping at the different levels where the mine branched out. Underneath the cage was place to store the ore for the trip back up. The first time he rode down in the cage he was amazed at how it shook back and forth as it raced into the earth.

The man who trained him did the job in a week. Within two weeks he was named supervisor and his pay shot up to a thousand pounds a months. He was rich.

Just a mile or so from the mine was a neighborhood of basic bungalows where white workers lived. He bought one after being on the job for a month. He paid cash for the place. It wasn’t fancy but it was better than anything else he’d lived since he left Chichester.

Two bedrooms, a sitting room and a kitchen. A place to park his motorcycle. There wasn’t an indoor loo, but the one out back suited him just fine.

The gold mine operated seven days a week, Marshall worked six. Sometimes seven, if there was a problem at the mine head. But he saw in a hurry that the best way to keep this sinecure was to make sure that nothing screwed up with the cables and there were no accidents. Compared to life on a ship, this was a cakewalk.

When it came to place names, the Afrikaners were not too original. They put fontein or fountain on the end of everything. Bloomfonten. Kruidfontein. They even had a bizarre place called Tweebuffelswordmorsdoodgeskietfontein. You should see the road sign. The literal translation is: Two-buffalo-are-shot-stone-dead - fountain.

Turfontein was the name of the racetrack. And it was right in Marshall’s neighbourhood. It meant the swells had to come from the northern suburbs for a day’s racing, but it also meant it was close to Marshall’s bungalow.

“I bought a couple of horses and started to train them and race them. Being a supervisor I could get away from the mine when I had to. The mine paid good money but I really started to make money with the horses.”

The time in South Africa was a good couple of years for Marshall. He learned more about the racing business and at a big city track. He built up his stable, and at one point owned half a dozen horses. He had never been so rich and wouldn’t be again until after the war.

He bought a car and he bought an old plane, a Tiger Moth. It was a bi-plane. Used would be an understatement. It was probably a military trainer at one stage. The plane had dual controls, so it could be flown from either of the two open cockpits. It was not a plane you’d like the fly in cold weather, but it was a perfect way to see Africa.