Coffee Surges

As someone who visits a coffee shop every morning, no matter where I am, the price of an Americano is moving higher. Paying C$5 or more is the norm.

And the reason is poor crops in many of the places that grow coffee, in particular Brazil and other parts of the Americas. The picture below is of a man harvesting coffee beans in Guatemala.

Coffee futures in New York closed above $3 a pound on Friday, a 13 year high.

The Financial Times reporting that coffee prices are up 70% in the past year. The FT pointing out that Starbucks alone buys three percent of the world’s coffee to supply its latte hungry customers in 40,000 retail outlets.

A Winter’s Tale

It snowed in the Eastern Townships on Sunday and there is already a lot of snow in western Canada. Paris had snow, rare for France at this time of year.

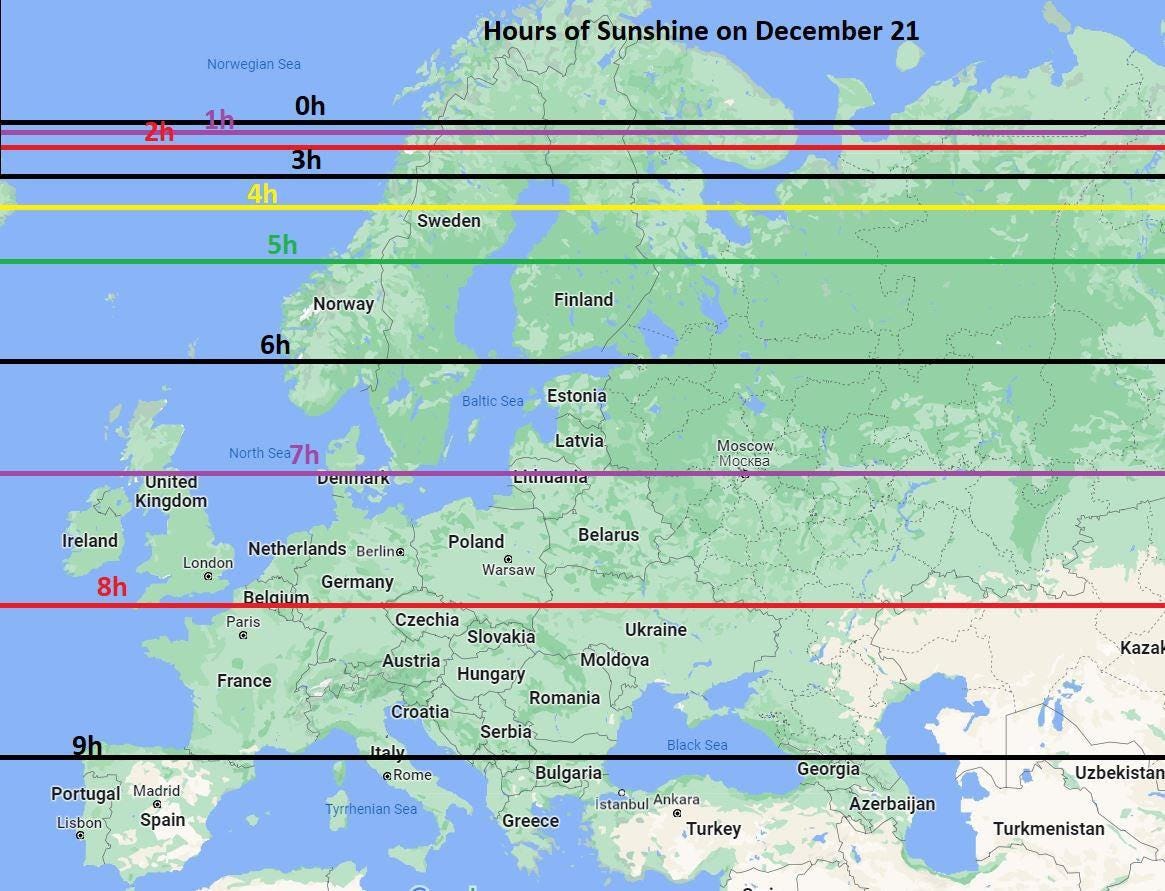

Winter, and the late fall, is also a dark time of year with short days in the northern hemisphere. Here are three looks at sunshine, and the rare places in Canada where it is relatively warm.

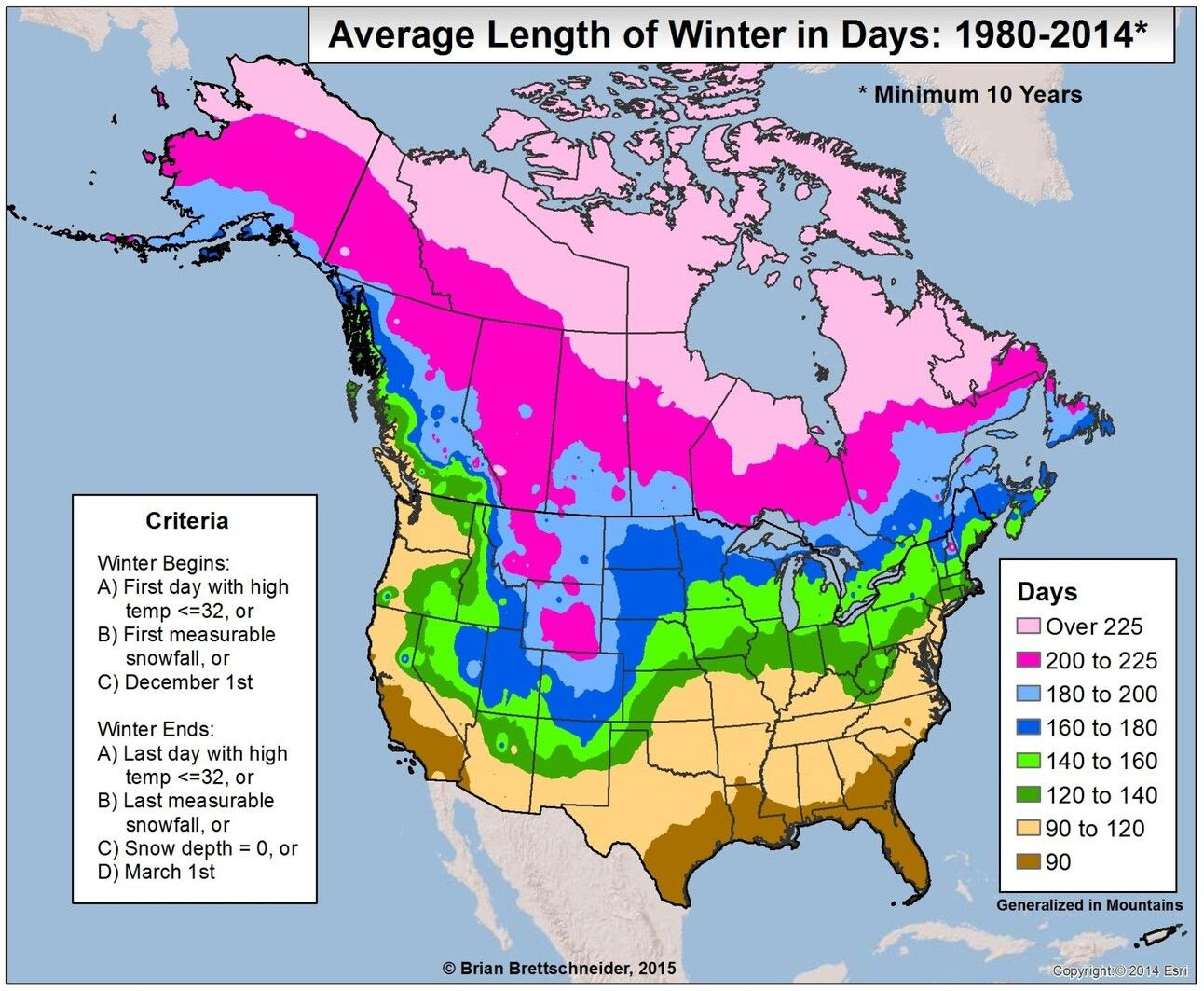

Measuring Winter and Not by the Calendar

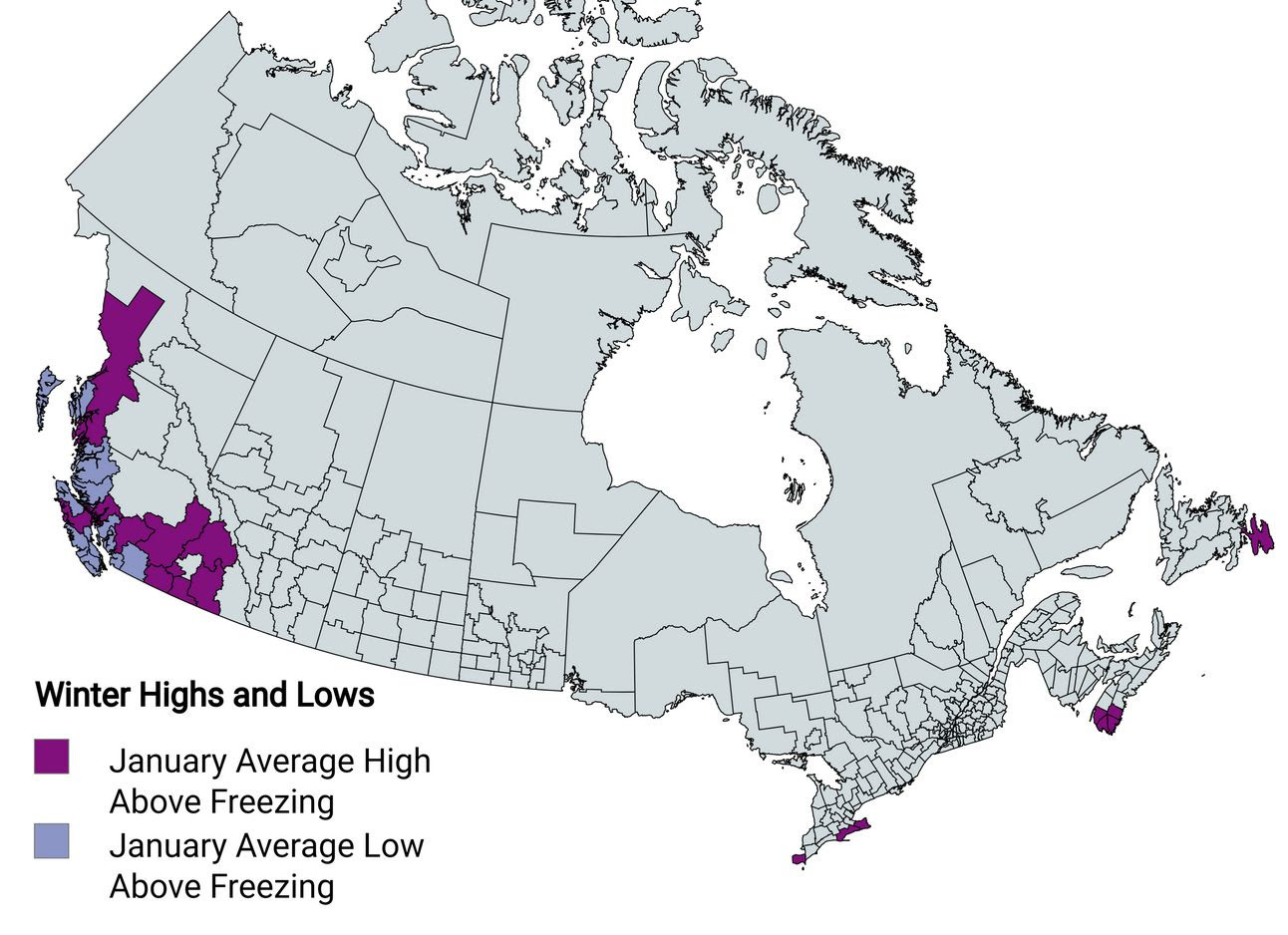

Places In Canada With Winters Above Freezing

Sunshine in Europe on the Shortest Day

Two Beautiful American Cars

Around 1964 I had a summer job as a `lineboy’ at Laurentide Aviation, a Cessna dealer at the old Cartierville airport in Montreal. The job was fueling planes and taxiing them around the runway. The dealership and fl sightchool was owned by four brothers, all Second World War pilots, and each of them drove one of these.

A mid-60s four-door Lincoln convertible. One of the cleanest most beautiful American cars of the era, and a lot subtler than the Cadillacs of the era. It had `suicide doors’, that is the back door opened so that if it got hit, so did the passenger. A mint condition of of these Lincolns can fetch more than $100,000 today.

Speaking of Cadillac, this a 1940 Cadillac convertible. Detroit was still making cars but after Pearl Harbor auto plants switched to producing B-17s and Sherman tanks.

The Loaves and The Fishes

From a subscriber in France. “If Jesus were to feed 5,000 people today.”

For non-French speakers, from the bottom left: “Is it halal? Is it organic? I can’t eat that, I’m vegan. Has the fish been tested for mercury? Is the bread gluten-free?

Essay of the Week

This is the opening chapter of a book I have been working on with Dr. Robert Francis. Little did I know when I wrote the chapter below that I too would have open heart surgery. In late July I went to Dr. Francis’s clinic, at his suggestion after a phone call about chest pain. I arrived at 9:15 am and left in an ambulance at 11:15. That’s another story. Here is chapter one of the as yet unfinished book.

Chapter 1

The Young Jogger with Heart Disease

It was the fall of 2021, and Dr. Bob Francis, the father of private medical clinics in Canada, was putting the finishing touches on his new clinic in downtown Toronto. Its name is ReGen Scientific, chosen to make clear that it offers the best medical science has to offer to regenerate the health of its clients. Using a brain MRI, ultrasound services, and in-house blood lab, which provides so much more information for a patient than they would get from their regular GP, and the latest cardiac testing technology, it is able to check out heart health symptoms such as chest pain appear.

Dr. Francis’s medical philosophy is simple: diagnose what is wrong with a patient before there is a medical crisis. He says the current medical system in Canada often waits until there is a medical crisis before taking any action.

“When you consider that 65 percent of patients who have a heart attack will have had no prior warning, and that 50 percent of heart attacks will be fatal, early detection is more than worthwhile,” says Dr. Francis.

On November 3, 2021, a poster boy for benefits of this approach walked through the door of the ReGen clinic. We’ll call him William. He had heard of Dr. Francis and how he had started and ran Medcan, which became the largest private medical clinic in Canada. William had learned that the ReGen clinic offers a super personal care plan — patients are even given Bob Francis’s cell phone number — and had heard that he could call if he had a hangnail. Well, maybe not a hangnail, but you get the drift.

A man in his early fifties, William ran every day and did weight training twice a week. He was rich, which is usually good for your health, well educated, and had never smoked and or used recreational drugs.

“What I quickly discovered, was that this guy was unlikely to make it to sixty,” says Dr. Francis, looking back on this case. Let’s see how he made that diagnosis.

William booked in for the checkup, an experience that is so different from the regular checkup at a GP’s office. First, there is a preliminary interview to get a detailed background about the person’s medical and family history. That is followed by a four-hour exam that, among other things, involves a blood test, where the in-house laboratory looks for eighty different markers; a full ultrasound looks at internal organs; and there is a stress test using a treadmill or stationary bicycle. That test uses wireless technology to get an accurate picture of heart health.

“When William came to see me, I had never met him, but his medical history told me that his father had a heart attack at the age of forty-seven and died in his early sixties,” says Dr. Francis.

The patient jogged every day and like many runners he was convinced that exercise protected him from heart disease. “It’s the Jim Fixx idea — he’ the marathon runner who died with his sneakers on while jogging at the age of fifty-two,” says Dr. Francis. “Jogging may make you feel good, and it certainly helps you with your ability to run a marathon, but it doesn’t necessarily have an impact on genetic-driven heart disease. Doctors today don’t take histories of their patients and their families into account because they don’t think it’s necessary. I know it’s important.”

At ReGen, the patient comes in a week or so after the tests are done. Dr. Francis goes through the results of the tests with the patient, one on one. In the case of William, he wanted to put aside looking at the genetic information at first and instead slowly build a case from the lab work. “I wanted to take a look at his lab work and see if there was anything there that would stand out. I wasn’t playing a game, but I wanted to educate him on the value of lab tests,” says Dr. Francis. “Sometimes I can give the patient an insight into how I am going to approach their body by looking inside out as opposed to outside in. So, I circled what I thought was relevant.”

One of the things that stood out, and something that is almost never diagnosed in a regular medical checkup, was William’s electrolyte levels. The ReGen blood test looks at four electrolytes: sodium, potassium, fluoride, and carbon dioxide. In William’s case, an elevated level of carbon dioxide in his blood was the red flag.

As part of building his case, Dr. Francis asked William if he had sleep apnea.

“Yes, I do. Why do you ask?”

This was an early indicator that William might be suffering from serious heart disease.

“Well, if you have sleep apnea, you maintain carbon dioxide when you sleep because you stop breathing part of the time,” Dr. Francis told him. “That’s important because the retention of carbon dioxide puts a big strain on the cardiovascular system. I told him he was putting a strain on his heart, and we should look at the results of the treadmill test before we got any further.”

Dr. Francis started using a treadmill test when he started private practice forty-seven years ago, something the medical establishment frowned on at the time. That day, he was looking at the readings of a man who runs every day. It told a tale.

“There was something wrong with his heart. That led me to go with a coronary CT scan. With a new patient, I like to do a cardio work, particularly now that we have new technology. But the government does not pay readily for it. You can’t just call up your doctor and say, ‘I want to have a coronary CT scan,’” says Dr. Francis. The coronary CT Scan costs $2,500 and it is not something the regular “free” system will pay for.

The next step was an angiogram, a test that takes X-ray pictures of the coronary arteries and the vessels that supply blood to the heart. Sometimes it can show that what is needed is a stent; inserting it is a relatively simple procedure. But William’s case called for something more than just a stent.

Dr. Francis told him he needed open heart surgery. Not an easy thing to hear. Imagine the shock to a man who considered himself fit because of his running regimen. But with the knowledge of his situation in hand, he knew that with the assistance of Dr. Francis he might be able to prevent himself from suffering a massive heart attack. He might never have known the danger he was facing if he had been in the public system, which tends to wait until something happens.

William agreed to go ahead with the surgery. It is a serious operation, something that was first done only seventy years ago.

“There are two parts: part A is open heart surgery. He would have to have veins taken from his leg; that’s where the new artery comes from. That would take five or six hours or even a bit longer. Sometimes, if a patient needs to have a valve replaced, which is not uncommon due to calcification of the valve, the doctor will do both procedures during the same opening,” explains Dr. Francis.

“At Toronto General, I’ve got about four lined up right now. One guy will need the valves replaced, plus he needs the bypass,” says Dr. Francis. “So, my program normally is to get to a point where I need to engage all the hospital-based specialists. The first one is the angiogram, which allows us to certify what we saw in the coronary CT scan. With the guy I mentioned, they did the angiogram, and they couldn’t even put in a stent.”

The open-heart operations are covered by provincial medical plans because they are classified as “medical need,” but government-run health care plans are reluctant to pay for angiograms.

“The biggest challenge in getting these patients through the system to allow them to [get] an angiogram. The angiogram is where they put a catheter in your artery and they look down into the arteries themselves in the heart,” says Dr. Francis. “The angiogram is a true diagnostic tool, but the health system won’t pay for the coronary CT scan as they say it’s not necessary and they are reluctant to have a doctor do an angiogram because of the cost. So, we are fundamentally challenged as a country because if they can’t automatically authorize it then we have to go to the next step.”

William’s story illustrates what makes Bob Francis so popular with his patients, and why he is in such demand. He takes a detailed scientific approach and is able to diagnose things such as heart disease long before the patient shows up at the emergency ward of a hospital with chest pains — or worse.

“Well, he certainly wouldn’t have been detected right away in the health system,” says Dr. Francis.

He says there were things that pointed to the early diagnosis.

“The first thing was family history: if one or both of your parents died of coronary disease under the age of sixty then that tells me that you have a genetic disposition. The second thing was, I looked at his lab tests and his carbon dioxide was elevated, and I asked him if he had sleep apnea, and he said he did. I told him he was not excreting it through respiration at night. Then the third thing was the elevation of the bad cholesterol (LDL). We never knew that before. It was through an evolution of knowledge. So, there were three evidence-based issues, family history, untreated cholesterol, and sleep apnea.”

***

This book tells the story of Bob Francis’s life, but it also presents his take on the Canadian medical system, something he thinks is broken. He has operated pretty much outside that system for thirty-eight years. In his view, the problem is with the general practitioners, who are the gatekeepers to the medical system. Dr. Francis doesn’t blame the doctors, but the system — introduced decades ago by then federal minister of health Monique Begin.

“The system today hasn’t changed: the doctor has to see ten people a day for twenty bucks. That’s two hundred dollars an hour. How can you build a business on two hundred dollars an hour? You have to have a receptionist and a nurse,” says Dr. Francis.

“It was okay up until 1985. I would always say to the patient, `I am going to charge X, and I am going to bill you on what I think is a reasonable hourly rate.’ Up until the Monique Begin changes, we had the dual system. I could bill OHIP (the Ontario Health Plan; health is a provincial responsibility in Canada, but the Federal government makes the rules) direct, or I could bill the patient because I liked to talk and take time with the patient.”

“People seem to have this romantic attachment to the Canadian healthcare system. They think it’s wonderful, and it was wonderful up until 1985; we had a duality, we had hospitals that got paid to see you, and we had great doctors who got paid to see you tomorrow and do their surgery.”

Hillary Clinton tried to introduce a Canadian style health care system when her husband Bill was president of the United States. In the 1990s Dr. Francis was asked to go down to the United States as part of the public discussion on reforming American health care. “I was invited to go down and debate John Kerry on the fundamentals. Monique Begin had already started to ruin the Canadian healthcare system. Clinton and Bernie Sanders were there. I pointed out with the use of slides where the healthcare system was and where it was going. I told them that if you go with Hillary this way, you’ll have our kind of system.”

***

Conrad Black is a patient of Dr. Francis. In some ways, he is a typical private patient, but in other ways, he is unique. As a man who lived and travelled all over the world, he agrees that Canada’s medical system has fallen behind that of other rich countries.

“Canada has joined the distinguished ranks of the North Koreans as the only other country in the world that doesn’t tolerate private medicine. That’s in theory, but in reality, private medicine does exist,” says Black. As someone with a keen interest in history and public affairs, Black has researched Canada’s medical system. He has discovered that just two people decided on the Canadian system: Pierre Trudeau and his health minister, Monique Begin. “There was sort of a whim as I understand it right at the end of the preparation of the legislation where she and Trudeau took the stand that ‘the hell with it, we’re just going to make it a single payer, all-state system and the hell with it.’”

If Black is critical of Canada’s healthcare system, his is full of praise for Dr. Francis. “Bob Francis is an amazing diagnostician. I got a check-up from him personally and he is very thorough. Fortunately, I’m not a guy who has had a lot of medical problems, but from time to time, I have had occasion to call him even if it was to get something for a cold or something like that. He always diagnosed things exactly accurately; he is an amazing diagnostician.”

Black is open about his time in prison and grateful for the long-distance help Dr. Francis provided. “When I was a guest of the great American people, I stayed in a facility that supposedly had a medical capability. But the doctors there were absolutely ludicrous, and whenever anything came up, which wasn’t often, I would phone him from there and he would say, `Well, I’ll tell you what that is …’ and he always had it right. I have a slight tendency, not to hypochondria, but to worrying that minor things might be more important medically than they are, and he was a very good man to put you at ease that way.”

There was one thing that was worrying, because it was something he had come across in his research on an American president. “I was afraid I had a phlebitis in my leg because I was sort of limping, and he said, ‘No, no, that it was something like water on the knee; don’t worry about that. We’ll take care of that when you get back.’ It was shortly before I came back. I was worried that it was one of those big clot sorts of things like Richard Nixon had where it was eight inches long. There have been a number of things like that.”

“From a straight user standpoint, I would say it’s a tossup as to whether France or Germany has the best medical systems, but in terms of combining convenience, the availability of doctors and facilities, and manageability from the public financing side, I think Australia has the best system. Those are the three contenders I see,” says Black.

“The Americans have a fabulous system for 70 percent of their population because they are on plans of some sort or another — usually not government ones. They manage them through the tax system because it’s the companies that provide all this stuff. It’s an absolutely fabulous service, covering everything, and it’s a deductible expense to the employers, so it’s state medicine in a sense but not the kind we have here. The 30 percent that aren’t on those plans do get, contrary to Canadian mythology, medical care, but the quality isn’t good; it’s often inferior to what a rich country like that should have.

I have never been very impressed with the British system. The best medical care in Britain is in the American hospitals over there. But whenever we have needed anything medically in France or Germany, I have been astounded … the hospitals are like hotels. You go right in, and you’re promptly taken care of and you pay them something like twenty bucks at the end of it. But it costs them a fortune; it’s a very heave fiscal burden for those countries.

Our problem here is we don’t have enough doctors. The number of doctors per capita is very low in this country: we are lower that Argentina, lower than Cuba, and all sorts of places.”