Dividend Stocks, The St. Lawrence Seaway and Dave Boxer, a DeeJay from the 60s.

July 22, 2024 Volume 5 # 9

Dividends Go Better with Coke

Coca Cola is a great dividend stock, says Barron’s, in a week when a lot of tech stocks took a hammering. Coke is one of the stocks that has increased its dividend every year for at least the last 25 years. On Friday Coke’s yield was 2.97%. The stock is up almost 11% since Santa last came to visit.

Dividend stocks getting another boost by the clever Rob Carrick in the Globe and Mail. He points out that Fortis, an energy producer, yields 4.3%. But one of his readers points out that if you bought the stock in 2000 and held it the yield on your purchase price would be 26%. Clever, but few people hold on that long.

The World’s Most Profitable Company

Saudi Aramco produces 9 million barrels of oil a day, more than any other firm and nearly a tenth of the world’s total. The state-run oil giant is the world’s most profitable company, generating $722 billion in profits between 2016 and 2023.

An article in Fortune says Aramco can reach net zero without producing less oil.

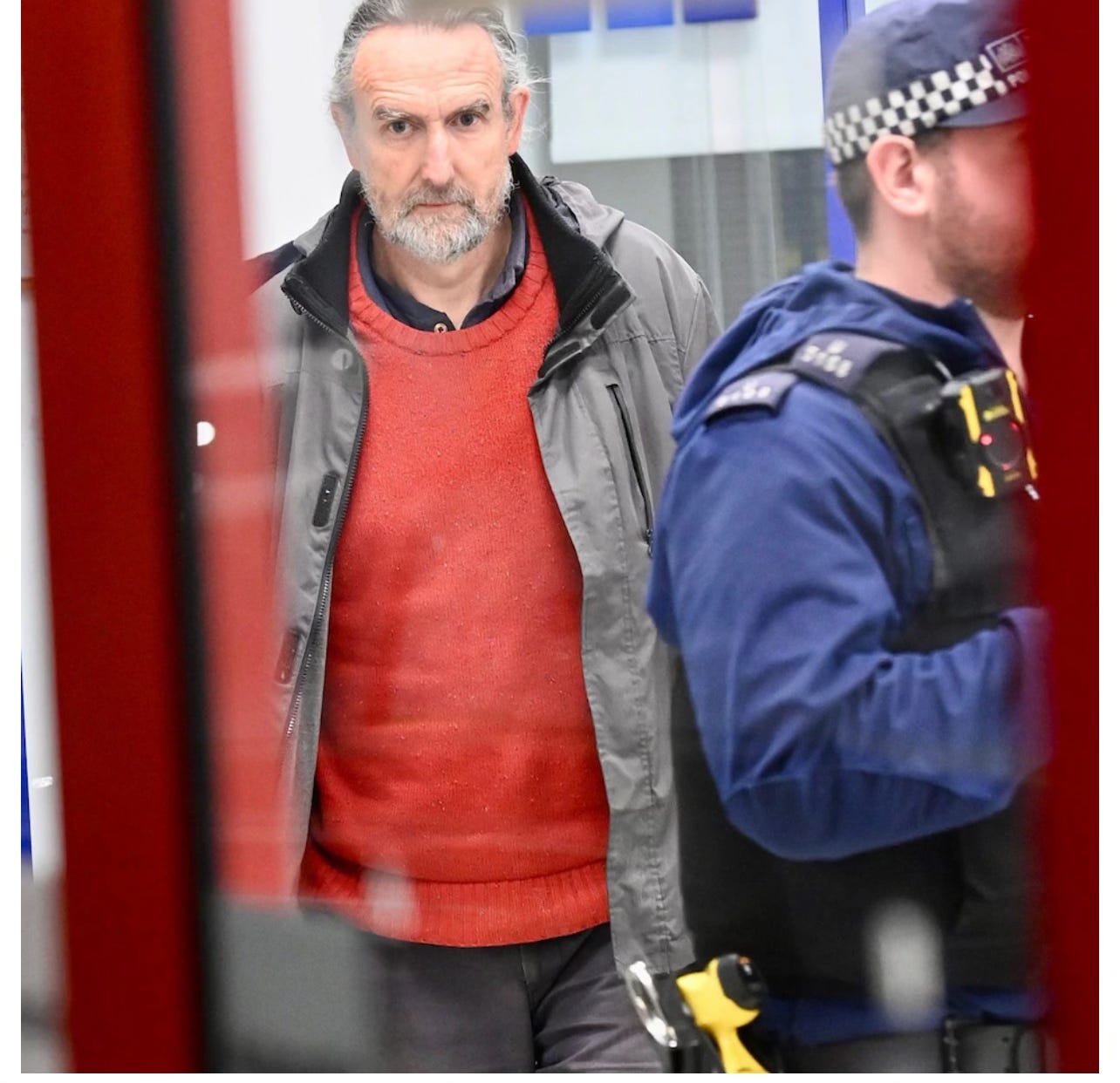

Just Stop Oil

One group that won’t swallow the Saudi promise is Extinction Rebellion in Britain; they want an end to all fossil fuel. Its co-founder, Roger Hallam, was sentenced to five years in prison this week for protests to stop traffic on the M-25, the highway that circles London. Four of his colleagues were sentenced to four years.

The M25 shut down in 2022.

Supporters of Hallam and the four others jailed called for the Labour govenrment to review the sentences. Newly-elected Prime Minister Keir Starmer says he won’t.

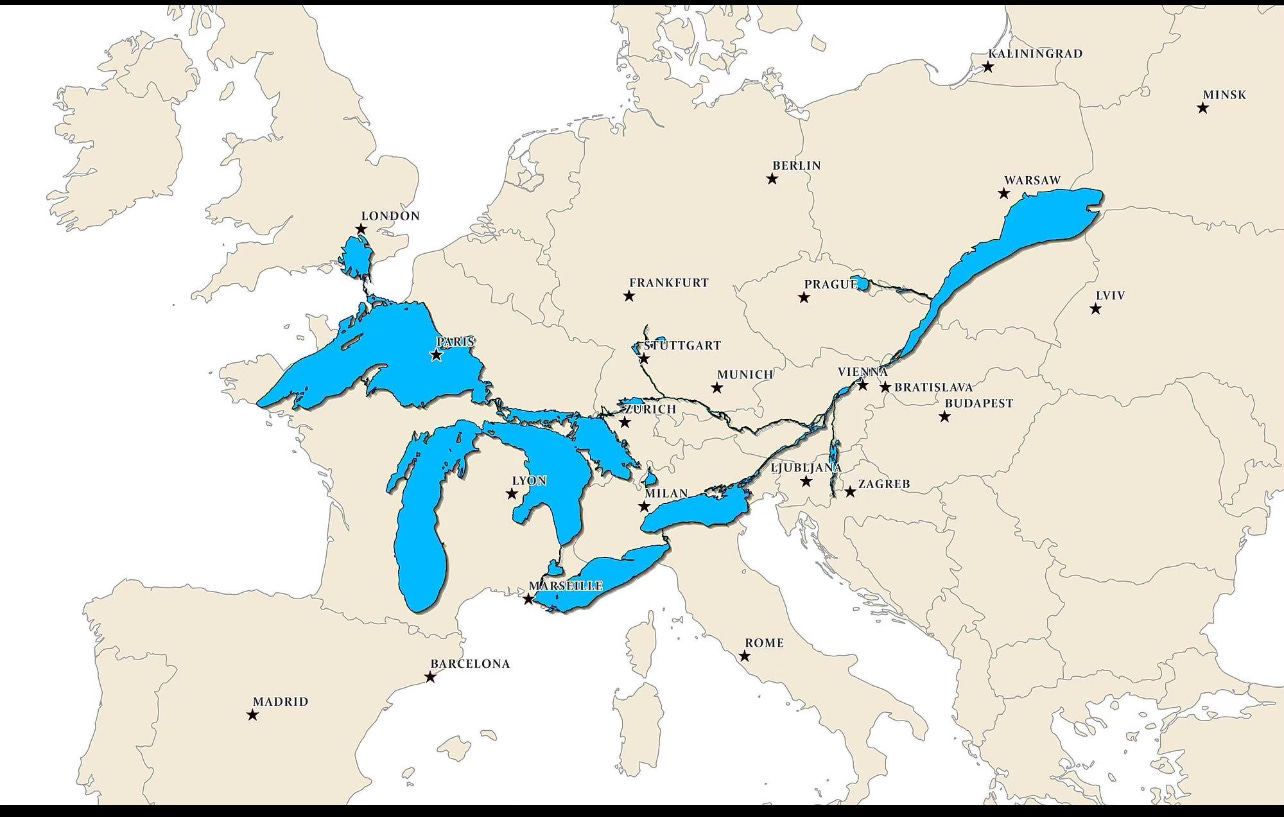

The St. Lawrence Seaway Superimposed on a Map of Europe

The St. Lawrence Seaway runs 2,430 miles from the Gulf of St. Lawrence at the Atlantic Ocean to the ports on Lake Superior, Duluth, Minnesota, and Thunder Bay, Ontario, and dozens of others along the St. Lawrence River and the five Great Lakes. The Seaway was opened by the Queen and President Eisenhower in 1958, allowing large ocean going ships to bring in goods from around the world and take out grain, iron ore and other raw materials.

About ten years ago I travelled on a ship owned by Fednav from just outside Montreal to Toronto. It was a scorching hot summer morning when we got to the first lock at St. Lambert, across the St. Lawrence RIver from downtown Montreal. The crew took out hoses and washed down the deck of the ship, not to clean it but to cool the metal. The heat bends the huge vessel at each end, meaning it could scrape bottom and not be able to make it through the lock. Fednav’s ocean-going ships just fit into the locks.

The cool water shrinks the metal and we move on, going through another lock near Montreal, then a pair of locks at Beauharnois in Quebec, another at Iroquois, Ontario, and then the Eisenhower Locks near Massena, New York. Both places are where the river narrows. At a golf club near Iroquois after a few drinks players aim golf balls at the ship, making a loud echo; the crew report it but nothing ever happens.

The ship then speeds through the narrow channel of the Thousand Islans, passing cottages big and small on the Canadian and American sides before entering Lake Ontario. On this trip the Fednav ship had spent thirty plus days travelling from Brazil, carrying 21,000 tons of sugar bound for the Redpath Sugar Refinery on the shores of downtown Toronto, surrounded by condos and shops. I calculated the cargo of sugar could be split into five-million sugar packets at Starbucks or Tim Hortons.

We got off in Toronto, but the ship continued on. If it had to, it could go through more locks to make it as far as Lake Superior. We were once in a fish restaurant in Tropea in southern Italy when the owner’s father, on learning we were Canadian, began talking about being a a cargo ship in the `Canali San Lorenzo’. The old sailor is the man on the far left in this photo below.

It took us a minute or two to figure out he meant the St. Lawrence Seaway. He was probably picking up a cargo of Durum Wheat from Western Canada, the stuff they make pasta from. Sad to say the European Union has banned the import of Canadian wheat because of some chemical used on prairie wheatfields, so Italian sailors are denied the pleasure of crusing down the Canali San Lorenzo.

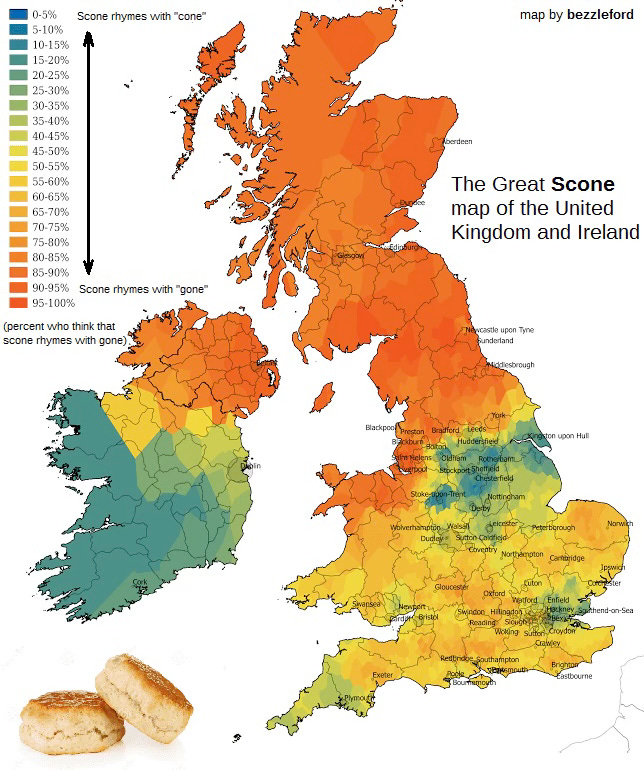

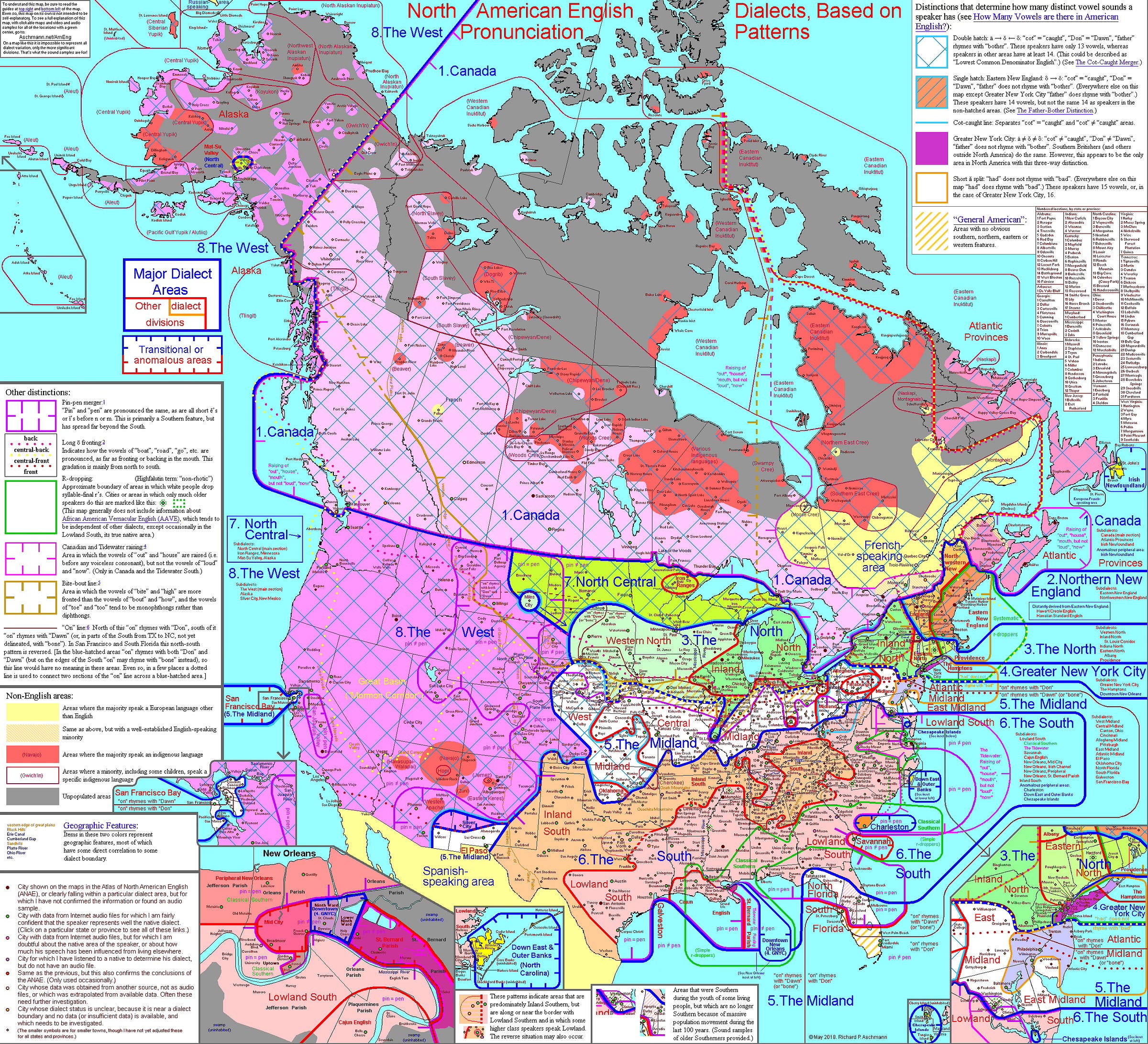

More on English Accents

Stumbled across this map of how scone is pronounced. I’m a cone man.

While Canadians think they have a homogenous accent, there are differences

These are pretty broad accent groupings across Canada and the United States. Brits think both sound alike, and you can’t blame them, the differences between a person in Los Angeles and someone in Toronto are subtle. Newfoundalnders have a distinct accent. But some sound Irish, while others speak like an Englishman from Shakepere’s time after your listen to the YouTube video of how Shakespeare really spoke. Even in French-speaking Quebec there are at least four distinct English accents and there are a lot of French phrases thrown in. If I burn myself I am liable to swear in French. Peter Cullen, a comedian friend of mine, used to do a standup act where one of his characters was Vernie Verdun, using the working class English accent of Verdun, an inner Montreal suburb.

Chicken showers.

Chickens bathe by scrathing and covering themsleves in soft dirt, as this black chicken is doing. She is a Jersey Giant cross.

Essay of the Week

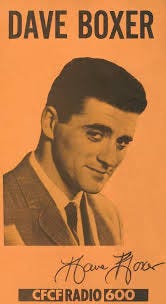

Dave Boxer was the top rock disc jockey on English-language radio in Montreal in the 1960s, an era that saw the transition from Elvis Presley, Pat Boone and bubblegum music to the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and the Kinks.

“Back in the 1960s you didn’t just listen to radio, you listened to Dave Boxer,” said Marc Denis, a retired Montreal disc jockey and historian of local radio. “And unlike his high-energy competitors he was more laid back and highly creative.”

Mr. Boxer ruled the roost through the mid-1960s, until other stations copied his winning format. Even though he had been off the air for almost six decades, news that Mr. Boxer died at the age of 89 on July 3 in Vancouver caused an outpouring of sentimental nostalgia in his hometown.

His real name was David Boxerman and he was born on Sept. 14, 1934, in Montreal. He was brought up in the Jewish neighbourhood made famous in the novels of Mordecai Richler, such as St. Urbain’s Horseman. His father, Moses, was a butcher who opened his own corner grocery store; his mother, Zelda (née Long), was a housewife. Moses Boxerman was related to the Wilensky family who still run a famous deli in Montreal.

Young David quit school after Grade 9 or 10, and set about educating himself.

“He was one of the most well-read people I have ever known,” his son Andrew Boxerman said. “He studied every subject and language; it was phenomenal the amount of stuff he taught himself.”

One of those languages was French; Mr. Boxer was fluent, rare for English Montrealers of the era. His teenage ambition was to be a radio announcer and he talked his way into the radio business, shortening his family name to Boxer when he went into radio.

The cliché in the radio game back then was that it all started at a 1,000-watt radio station. Like most announcers and DJs of the era he started working for peanuts in a small radio station, in his case CHNO in Sudbury, Ont., which did indeed transmit at 1,000 watts at night; big-time stations broadcast at 50,000 watts.

After working at a few smaller stations in Northern Ontario, Mr. Boxer moved to bigger markets, as radio people called cities. He ended up at VOCM in St. John’s, Nfld., for a brief spell. The station was owned by Newfoundland radio entrepreneur Geoff Stirling, who also owned CKGM in Montreal. That was Mr. Boxer’s next stop and he worked there for a while before making his big move to CFCF in 1963. He was 28 years old.

His program ran from 7 p.m. to 11 p.m., and his ratings were soon tops in the English-speaking market. He ran contests and when there was a winner he announced it with a sound from a slide whistle that he called the “fenortinizer.” There were predictions of what new records might make it, and there were Boxer’s Bombs for those he thought would not.

“He was very much in touch with that vibe of the kids and had a real connection with the audience. I remember going to watch him in the booth. He was really good at it; it was something to see,” Andrew Boxerman said.

Along with his radio program he ran dances on the weekend at a local curling club where he was the host and disc jockey. On the air Mr. Boxer used the telephone to connect to his young listeners. He even hired one of them.

Frank van de Ven was an immigrant from the Netherlands in January of 1965 and on his first night in Montreal he was welcomed by relatives who were listening to Mr. Boxer on the radio. “There were call-ins and I telephoned him and he asked me to come to the station,” said Mr. van de Ven. Soon he was working at the station and some nights was the operator on the Boxer show.

“Back then the DJ didn’t spin the records, he sat in the booth and the operator played the records and the commercials,” Mr. van de Ven said.

When the Beatles and other rock stars visited Montreal, Mr. Boxer was there to greet and interview them. He needed them and they needed the publicity and record sales a top DJ could generate.

After just a few years, however, competition toppled Mr. Boxer from his perch at the top of English-language radio in Montreal. George Morris, known on the air as Buddy Gee, was a rival at CKGM, but his ratings never topped those of Mr. Boxer, according to Marc Denis, a Montreal radio historian and former disc jockey.

In addition to Buddy Gee and CKGM, Mr. Boxer also had to contend with an upstart from the suburbs. Gordon Sinclair, son of the famous Toronto journalist, bought CFOX, a small station in the west island suburb of Pointe Claire and soon switched the format from country and westerm to rock ‘n’ roll.

In the late 1960s, Mr. Boxer left announcing and began a successful career selling radio ads for CJAD. He did return to broadcasting in the early 1980s doing an oldies show on CJFM.

He also ran the David Boxer School of Broadcasting in Montreal, operating in both French and English. His son Andrew says he trained some future radio stars.

Mr. Boxer married Bracha Rosenblum in 1966; the couple had two sons, Eddy and Andrew Boxerman, and separated in the early 1980s but they never divorced. Ms. Rosenblum is still alive, as are both their sons. His other survivors include three grandchildren and his sister Helen.

Mr. Boxer was intensely curious, always learning and even his hobbies were demanding. He was a ham-radio operator, which involved acquiring special transmitters and antennas as well as getting an international licence. He also learned to fly at an airfield in Montreal.

“He had a pilot’s licence for many years and when he was younger, he used to take me and my brother and our friends up for joy rides in a Cessna,” Andrew said. When he spoke to his father two weeks ago, “his deep voice was as recognizable as ever,” he said.

Though Mr. Boxer was the king of rock ‘n’ roll on the radio, it was a different thing at home.

“My father loved music but we never listened to rock ‘n’ roll or popular music in my house. It was always classical music. My brother and I weren’t the fondest of classical music back then, but I like it now.”

Mr. Boxer was keen on education, exposed his children to as much as possible and sent his sons to private school. Both of them have university degrees. He bought an Apple II Plus computer for the household in 1977 and both of his sons quickly became so computer literate that both went on to careers in computer technology. Eddy Boxerman invented a best-selling computer game called Osmos.

In the mid-1980s Mr. Boxer moved to Vancouver, where he opened a restaurant that specialised in smoked meat and other Montreal delicatessen specialties from his old neighbourhood. It was called DJ’s Deli and some nights he would pick the music from his old time slot at CFCF. Mr. van de Ven, his former radio colleague, also retired to Vancouver and often met socially with Mr. Boxer there.

During his radio heyday, Mr. Boxer had the same signoff every night just before 11 p.m. He would play a saxophone tune by Boots Randolph and say: “It’s now elevensville. Off we go into the land of the giant marshmallows, to sleep deliciously, dee-liciously.” Then, after his signature “Goodnight bubby,” he was gone.