Elections, Cadillacs, Empires and an Alberta Farm Boy Makes it Big in Oil

July 8, 2024 Volume 5 # 7

French Election: The New York Times and The Guardian Breath a Sigh of Relief

Doom and Gloom Headlines at the Daily Telegraph

And this on the front page on July 4th, hours before counting the votes in Labour’s Victory Later that day.

Britain is teetering on the brink of bankruptcy. No one dares admit it

France’s Fifth Republic may not survive the week

President Kamala would be a disaster for the world

Was it the prospect of the Labour win that panicked the columnists and the headline writers? At last look Britain had not declared bankruptcy, the Fifth Republic was still standing and Gavin Newsom and Gretchen Whitmer won’t hand Kamala an easy victory if indeed Joe Biden pulls out of his Ruth Bader Ginsburg replay.

The Auto Empire That was General Motors, Ford and Chrysler

In 1950 the United States accounted for more than 80% of world car production. It is about 2.7% today, hit by competition from Japan, Germany, South Korea and others.

Above is a 1950 Cadillac convertible, with the earliest fins that would be huge by 1959. GM’s style guru, Harley Earl, was said to be inspired by the P-38 Lightning fighter from the Second World War. From the 1920’s to the 1950s car stocks were the equivalent of the so-called Magnifiicnet 7 tech stocks today, points out Barrons.

Nothing last forever. “Railroads, cars, chemicals, the Internet, AI in time, these giants are felled as creative destruction takes its toll,” writes Barrons. Another story I read somewhere reports that Amazon is 30 years old this week. Tesla is about half that age. They too will be replaced by something. The longest run a stock had on the Dow Jones Industrial Index was General Electric. It still exists, but its CEO is longer a God.

And Speaking of Old Empires: Sic Transit Gloria Mundi

Two Empires at their Peak: 117 and 814

Hadrian’s Empire

Charlemagne’s Empire

Two Empires at Their Peak: 1812 and 1942

Napoleon’s First Empire three years before he was shipped off to exile on St. Helena.

Hitler’s Third Reich three years before he shot himself in the Bunker in Berlin.

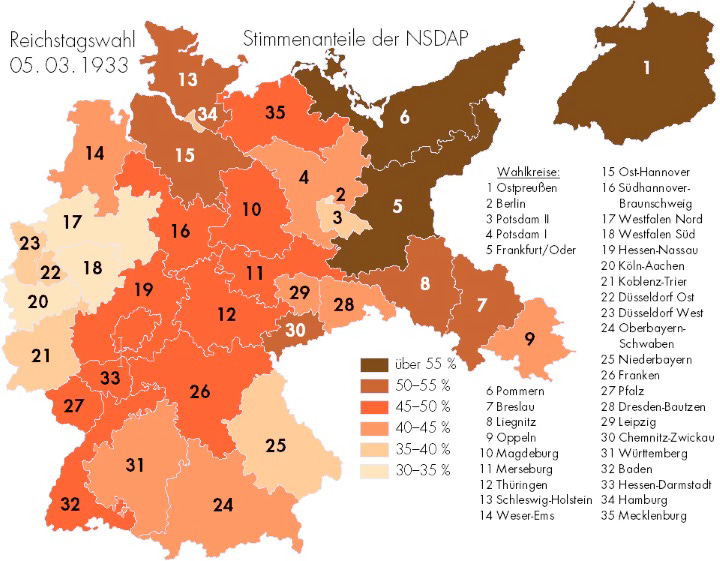

Who Voted for Hitler in 1933

The highest votes for the Nazis were in Prussia, with the exception of Babylon Berlin. The weakest support for the Nazis was in the the industrial west that would soon be bombed into the stone age. Someone pointed out this week that Paul von Hindenburg, the president of Germany handed the Chancellorship to Hitler in 1933, though he didn’t have to at the time.

The point was that von Hindenburg was 85 and almost certainly mentally feeble when he annointed Hitler, a man he didn’t really like. Sound familiar?

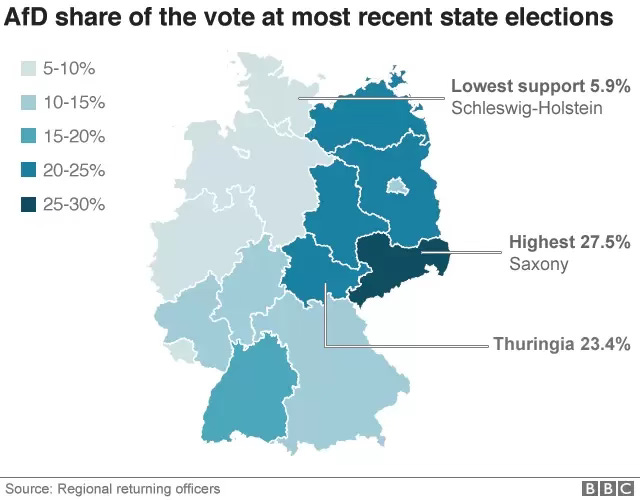

Who voted for the AFD in 2024

The results for the nationalistic AfD were highest in the places that voted for the Nazis in 1933 and that made up much of East Germany for 44 years.

The 10 Largest Cities in the World From The Times of India

The total population of those 10 cities is 255-million which if they were a country would make it the third largest after India, China, the United States and Indonesia. None of those cities is in Europe, only one in North America and one each in Africa and South America. Asia is where the people are.

Essay of the Week

A long obituary I wrote for the Globe in 2013 about a farm boy who made it big in the world of oil and came up with idea of Shale Oil.

Arne Neilson was a young geologist just a few years out of university when he led the team that discovered the Pembina oilfield in central Alberta, a huge conventional field that changed the face of the oil business in Canada. He later went on to help discover oil in Saskatchewan, the Sable Island field off the coast of Nova Scotia, Hibernia and the Gulf and Mexico and Louisiana.

Alberta’s Pembina field has been producing since 1953, and is one of the largest conventional oil fields in North America. It is oil that is much cheaper to produce than oil from the oil sands of Northern Alberta.

“My idea at the time was to find oil by looking at the pure geology,” wrote Mr. Nielson in an article in Alberta Oil in April of this year. His method was unconventional and the people running the firm he was working for at first dismissed his ideas, which came from studying electronic and physical evidence from wells drilled in the area. It was tedious work but it paid off.

“Creativity is one of the characteristics that makes the best geologists,” said his wife, Valerie Nielsen, who is a geophysicist and shared her husband’s scientific interests. “Arne’s creativity paid off in a big way.”

Mr. Nielson went on to become president of Mobil Oil Canada. His work on the geology of the Pembina field made his name at an early age and propelled him into a successful career in the Canadian oil business and that led to directorships in oil and gas firms and large corporations outside the energy field such as the Toronto Dominion Bank and Aetna Insurance

“For a geologist, one of your big objectives is to make a real oil discovery. What I found at Pembina I felt was an oil discovery that was a billion-barrel type in size,” said Mr. Neilson. “For a young geologist not many years out of university, it gave my career a tremendous boost.”

Arne (pronounced Arnie, the Danish way) Nielsen was born in 1925 on a farm in Standard, Alberta. His parents were Danish immigrants who first migrated to Iowa but moved to Alberta in 1910, encouraged by a land grant from the Canadian Pacific Railway. An entire Danish community moved north. Askel Nielsen, Arne’s father, had been a farm labourer in Denmark and Iowa, but he was able to buy a farm in Alberta with a 25-year mortgage from the CPR. Not only was land $15 an acre cheaper, but the weather was better.

“The winters were not as severe as they were in Iowa,” wrote Arne Nielsen in his memoirs published last year. “There were light snowfalls and weeks of warm weather during which the snow disappeared. In winter, regular Chinook winds occurred.”

The Danish immigrants valued education and didn’t complain about the school tax of $10 per hundred acres. Arne Nielsen was well educated and five of his nine children earned a total of nine degrees from the University of Alberta with others graduating from the University of Calgary and Harvard.

The CPR built a spur line to Standard, but it was still isolated. Standard is only 90 kilometres east of Calgary along the Trans Canada Highway, an hour’s drive away today but in the 1920s and 30s there were no super highways and no oil royalties to finance them. Alberta was poor. Young Arne Nielsen travelled to school and that was about it. He was 14 the first time he went to Calgary, a city whose business life he would dominate in later life. His mother took him to the big city to buy him his first suit for his confirmation in the Lutheran Church.

The isolation was a bit of a drawback for his father since he wasn’t that great at fixing things in an era when farmers had to be mechanics and carpenters, able to repair anything that broke since there were no tractor dealers nearby and few people to come and repair things. Rural telephone service was spotty, if it existed at all.

“His father loved studying rocks and he passed that on to Arne, along with his trait of not being able to fix things,” said Mrs. Nielsen.

Arne Nielsen was too young to join the Army at the start of the Second World War and enlisted in late 1944. He was being trained in the tank corps at Camp Borden when the war ended before he could go overseas. He was still listed as a veteran and qualified for government-financed education. He went to the University of Alberta where he earned a Master’s degree in geology by 1950.

His first summer job off the farm was with the Geological Survey of Canada in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains north of the Athabasca River. In 1949 he joined Imperial Oil and worked on the Leduc property discovered just two years earlier, starting the oil boom and changing the way of life in Alberta, as it became oil rich instead of a struggling agricultural province.

From the start he loved working in the field and he loved the oil business. “It was more than a job….it was a way of life,” he told the author Peter Newman.

After graduating he started work with Socony-Vacuum Exploration, then a small player in the Alberta oil exploration boom. It would later be re-named Mobil Oil. Mr. Nielsen He led the team that moved into the Drayton Valley and discovered the Pembina oilfield.

“Like many other great western Canada oil and gas discoveries, Pembina No. 1 defied conventional geological wisdom,” wrote Mr. Nielsen in his book, We Gambled Everything, the Life and Times of an Oilman, which made the best seller list in Calgary this year.

“In 1952 the conventional wisdom was that Alberta’s best oil prospects were in the Devonian-era limestone reefs – ancient coral reefs of shallow seas now locked up in the province’s geologic deposits. The Pembina discovery was made by going off in a completely different direction.”

Layers of rock and soil covered what was once a great inland sea. Each layer had a different name. Most people thought oil would be found in the Devonian strata. But there was another formation called the Cardium, formed in the time of the Dinosaurs when Alberta was tropical. It is same type of sandstone that makes up the white cliffs on Dover on the southern coast of Britain. But Arne Nielsen was looking in Alberta, sitting alone for hundreds of hours going over electronic logs recorded by exploratory drilling.

He had to convince his superiors that it was worth drilling. They were convinced oil could only be found the old coral reefs like those at Leduc. Mr. Nielsen thought there could be oil in the Cardium sandstone. The thinking was oil would seep through sandstone, but Mr. Nielsen said it would pool against non-porous shale in the next layer.

After discovering some `little puddles’ of oil one of his colleagues suggested `fracking’ or pushing fluid at high pressure into the well, the technique that has produced the shale oil boom in Canada and the United States. In 1953 it was a first in Canada.

On June 17, 1953 the first of many producing wells came in. The Pembina oilfield was born and is still producing today. Modern fracking techniques are extending its life.

“Pembina No. 1 was a great moment for my associates and me. It was particularly a triumph for me,” said Mr. Nielsen of the discovery. “I has achieved the dream of every geologist; discovering a large oilfield through exploration based on sound geological principles.” He was 27 years old.

Arne Nielsen went on to become the chief geologist of Socony-Vacuum and then was posted to New York, Denver and Houston. He came back to Calgary in 1966 as vice-president of exploration and became the first Canadian president of Mobil Oil Canada a year later.

In 1973 he was part of Canada’s first energy trade delegation to China, a year after Richard Nixon’s visit to Beijing. China was still pretty much closed to the rest of the world and this was one of the first western business delegations, led by Canada’s Minister of the Energy at the time, Donald Macdonald.

The Canadian oil executives travelled 3,000 kilometres through China, most of it by rail. They visited an oil producing area in Taching in northeast China near the border with the Soviet Union. He said the Chinese in the ear of Mao were secretive, but were excellent hosts and anxious to learn from Canadian oilmen, though they shunned any foreign investment back then.

“Canadians have probably forgotten how important we were in founding the Western world’s trading relationship with Communist China,” said Mr. Nielsen. “There is a straight line of sight between the China we encountered in 1973…and China’s presence (today) in world oil and gas – including the Canadian oil sands thirty-five years later.”

As a homegrown oil executive, Mr. Nielsen was courted to run Petro Canada, then a Crown Corporation. He recounted that he wasn’t that keen and “…influential people in Ottawa decided that I wasn’t political enough. I think that verdict was a compliment.”

One non-paid government post he accepted was as Honorary Consul of Denmark for southern Alberta.

In 1976 he left Mobil Canada and became president and CEO of Canadian Superior Oil, another subsidiary of an American oil giant. When he left his office at Mobil he had his secretary, Muriel Jones, to make a careful list of every item he took with him to avoid any conflicts. A prescient move.

About six months after he started at Canadian Superior Mobil Oil launched a lawsuit against Mr. Nielsen saying he and others took company secrets with them. Mobil was huge with revenues of US$25-billion compared to Superior’s revenues of $441-million.

“The basic charge was that I could not work for my new company in the exact same job that I had with Mobil without utilizing confidential Mobil information,” said Mr. Nielsen. That he was a star geologist as well as an oil executive seemed to worry the American parent of Mobil Canada.

In the end, the judge dismissed Mobil’s lawsuit. Mr. Nielsen was on a business trip to Chile when he heard the news.

It appears there were no hard feelings. When Mobil Oil acquired Superior in 1986 it also took over the subsidiary Canadian Superior Oil and Arne Nielsen was appointed chairman and chief executive officer of the merged company in Canada.

Earlier in that decade he was a point man in the oil industry’s battle against the National Energy Program, brought in by the Trudeau government in 1980. The NEP was in many ways a reaction to consumer and voter dissatisfaction with rising oil prices, which went from US$1.80 a barrel in 1970 to US$28 a barrel in 1980.

Mr. Nielsen blamed the indifference of Pierre Trudeau to Alberta for the policy. “He was perceived of as a man whose only contact with Alberta was to cross its airspace while flying somewhere else,” said Mr. Nielsen.

He remembered watching as the Energy Minister, Marc Lalonde—described in his book as “the number one bad guy” put forward his policy on October 28, 1980.

“We sat in front of television sets in our offices, mouths agape. Prior to that afternoon, we couldn’t have imagined anything the federal government could have done to us would have been worse than what they’d already done. We were naïve.”

Mr. Nielsen and other set up what they called the Alternative Energy Program. He felt they were better off dealing with Jean Chretien when eh was energy minister. There was also an incident in the early 1980s when Pat Carney, the Conservative Energy critic in the House of Commons was forced to use a separate entrance to the Calgary Petroleum Club because she was a woman. She came as an ally, not an enemy and Mr. Nielsen was on the executive committee when the club admitted women members soon afterwards.

When the Mulroney government, elected in 1984, introduced a new energy program called the Western Accord, Mr. Nielsen signed the document as the representative of the Canadian Petroleum Association. Pat Carney was then Energy Minister. Many of the ideas came from the Alternative Energy Program.

Arne Nielsen retired as CEO of Mobil Oil Canada in 1989. He was then on the board of a number of companies both in and out of the oil business. His main hobby was reading, especially military and natural history. He wrote one technical book: Cardium Stratigraphy of Pembina Oil Field, as well as his autobiography. In 2008 his family house, “twenty-eight feet by thirty-two feet with four rooms’ was moved to the Danish Canada National Museum and Gardens in Dickson, Alberta.

“It’s quite a privilege to be part of history while still alive,” was the closing sentence in Arne Nielsen’s book.

Arne Nielsen and his first wife, Evelyn had seven children. She died in 1975 at the age of 43 after suffering a heart attack in a Calgary restaurant. Several years later he –remarried Valerie Thomas and they had two children. He was pre-deceased by a son.