Hollywood North Dodges a Bullet, a Farewell to Italy and the Mayor of the Fair

May 19, 2025 Volume 6 # 7

Making Hollywood Great Again

On May 4 Donald Trump mused about putting a 100% tariff on movies produced outside the United States. It seems that idea will probably never see reality.

What Ever Happened to Tariffs? the Hollywood Reporter, the bible of the movie biz, asked this week:

“International film tariffs are just sooo last week.

Since Donald Trump announced plans, via a caps-lock post on May 4, to impose a 100 percent levy on “foreign-made” movies, it’s been all the film industry has been able to talk about. The (unprecedented) idea of a movie tariff system threatened to disrupt, maybe destroy, the global system of financing, producing and distributing films.

Trump’s tariffs might still be on the table — it’s hard to know with the easily distracted POTUS — but within the industry, the discussion has already moved on.”

A lot of Hollywood movies are produced outside of California, in other states, and other countries from Hungary— Budapest can be made to look like anywhere in Europe— and of course Canada.

In a good year the TV and film production business in Canada is about the same size as auto manufacturing. In 2023 it was $14 billion for film and TV production and $15 billion for the car and truck makers.

Making movies and television series employs 220,000 people in Canada, about twice as many as the car companies, though for the most part the factory workers have more secure work and higher pay. Canadian politicians are apoplectic about the prospect of tariffs and rhe political talk is often about the car industry and natural resources, especially oil. No one mentioned the movie biz until Trump’s musing about taxing foreign movies.

Economists and people in the business are hard pressed to figure out just how tariffs would apply to cross border movie and TV production, which in Canada is centred in Vancouver and Toronto with Montreal the location for animation and games.

Different types of production go to different cities. Vancouver gets a lot of American movie and television production. It is in the same time zone as California and a shortish flight from LA. Toronto gets some American production and a lot of Canadian movie and TV production. It’s not a hard and fast rule, but actors in Vancouver can make more money for the same work as actors in Toronto.

American production companies receive federal and provincial subsidies to work here.

“We support American production in Canada through tax credits. It’s hard to see the United States finding a way to put tariffs on. They already have such a good deal. For example, British Columbia increased its tax credits in December,” said a long-time industry participant.

Another echoed the idea that tariffs on TV and Film production are hard to imagine.

“I’m not expert, but I really can't see how a tariff would apply. Tariffs are on goods entering the country to be sold or to be incorporated into something that will be sold. Said goods would have a determined value to which the tariff would apply. Don't know how you would apply that to something like a film, especially if it was an American service production shooting in Canada,” says a union official in Vancouver.

Most studios are booked solid, helped by the tax credits, weaker Canadian dollar but also by the experienced crews and the modern studios in Toronto and Vancouver. One major studio owner, who wants to remain anonymous had this reaction to the prospect of tariffs: “The whole purpose of coming here outside of the fact that we are fully capable of producing film and television series and incredible ones, is the fact that we have an amazing tax credit and our dollar value.”

The LA fires earlier this year are another problem for Hollywood.

All the people who lived in those houses are gettting their lives back together and a lot of them work in the movie business. It has been devastating for Hollywood studios. The movie and TV business will still make money. The people who run Netflix and Disney don’t care where movies and streaming series are made, they care about making money and their share price. That’s why Trump’s bringing movies back home is an idea that has come and gone. But with the Donald, you never know. He might see an old movie that brings the movie tariff back to life.

Where the Money People Work

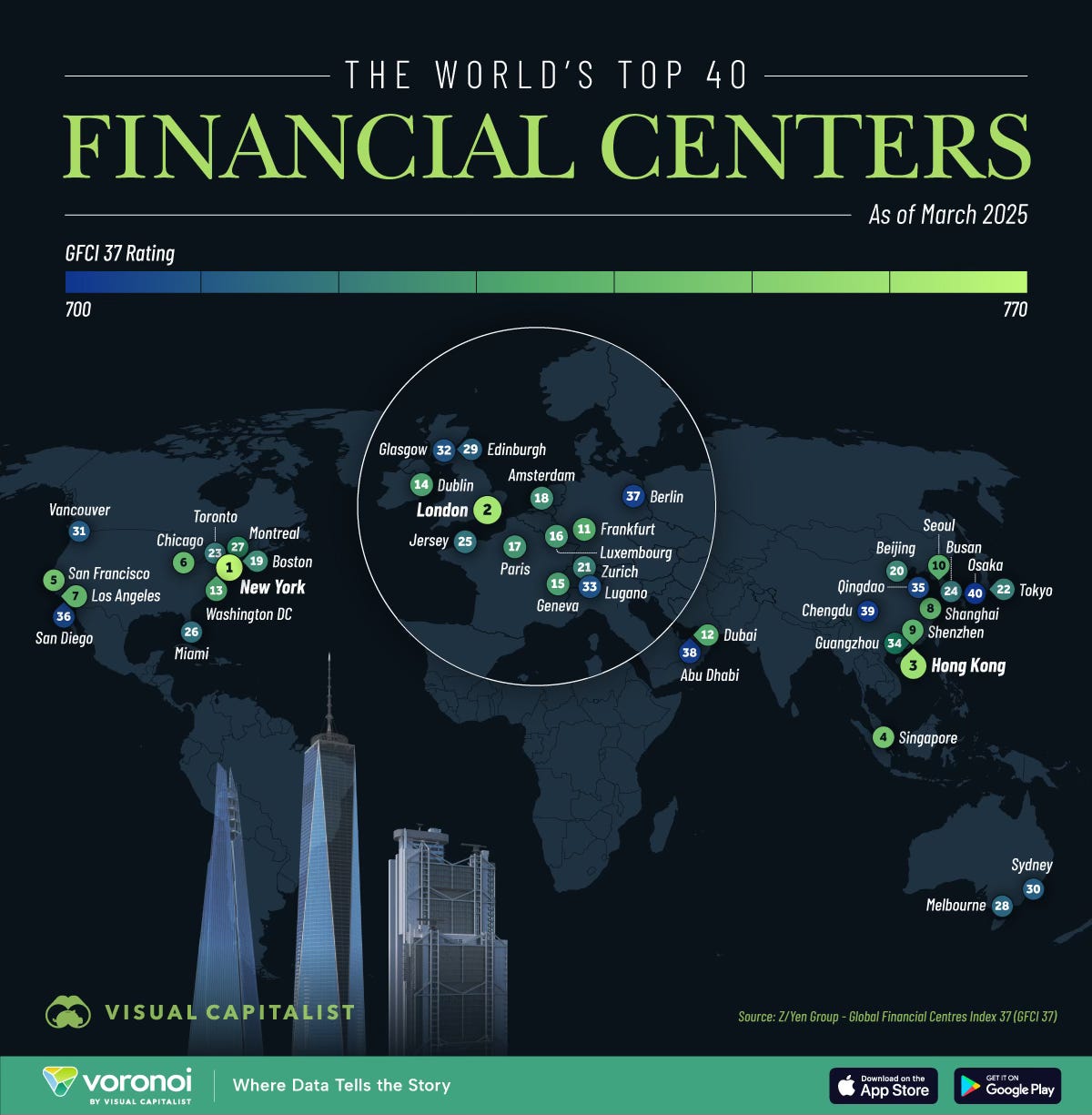

Speaking of Los Angeles, it is number 7 on the Financial Centre Top 40. New York and London still numbers one and two, but look at the next spots: Hong Kong and Singapore. Lots of action in the China-sphere.

If California Were a Country…

…it would be the fourth largest economy in the world. The economy of the state of Texas is between France and Italy and bigger than Canada.

Farewell to Italy and Camogli

The moon over the water from the window in our little apartment on the last night there. Jet lag means this newsletter is a little shorter than usual.

Names and Regions in Italy

Our Wonderful Camogli Friend Carola and her Dog Alba

Essay of the Week

This is an obit I wrote that was published in the Globe in April. I wrote it from Italy. I never met Philippe de Gaspé Beaubien, but I worked as part of his team at Expo 67 where I worked as a Press Aide, the best job I ever had.

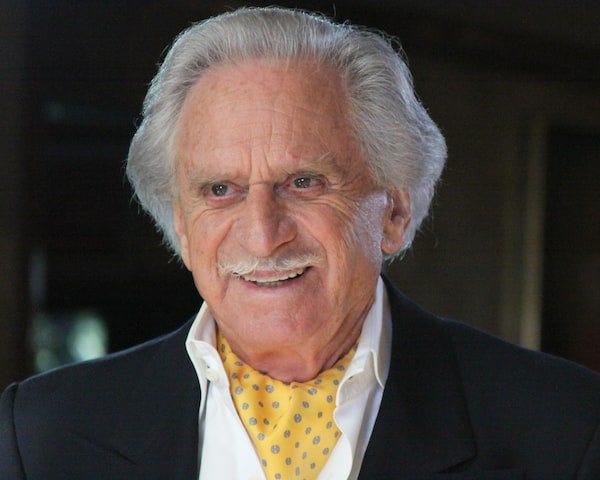

Philippe de Gaspé Beaubien, who died at his home in Quebec’s Laurentian Mountains on April 9 at age 97, was known as the Mayor of the Fair at Expo 67, the hugely successful world’s fair held in Montreal in 1967 to celebrate Canada’s 100th birthday. Mr. Beaubien was 35 when he was lured away from his entrepreneurial life in 1963 to become the director of operations.

When he started, it wasn’t certain that Expo 67 would be ready on time. There were federal politicians who weren’t keen on it, including Walter Gordon, finance minister in Lester Pearson’s cabinet. Even Mr. Beaubien’s own father predicted the fair would never open.

“The islands will float down the St. Lawrence River to Sorel,” said the father, also named Philippe, with whom the son had a rocky relationship.

At the time, the younger Mr. Beaubien seemed like the perfect catch: flawless in French and English, a Harvard MBA, a self-confident extrovert with movie star good looks. He never disappointed the people who hired him, and he became part of what were known as the Big Five, the men who built and ran what is now generally seen as the most successful world’s fair of the 20th century.

“He was the public face of Expo,” said John Lownsbrough, who interviewed Mr. Beaubien extensively for his 2012 book The Best Place to Be: Expo 67 and Its time. “He was a man who was very cultivated in his appearance. I was expecting someone a little bit more austere, but he had real warmth, which is why he got along with people. He was one of nature’s aristocrats, and a super salesman.”

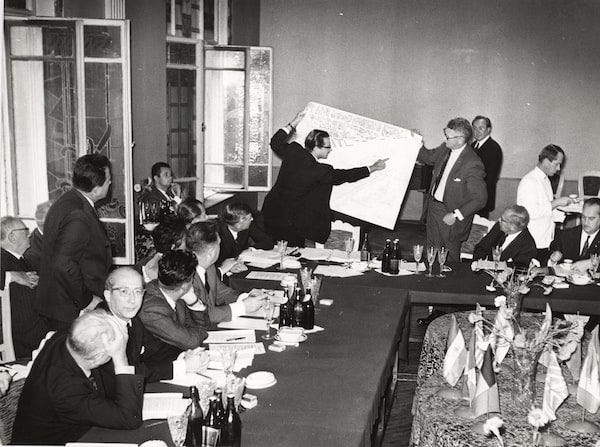

One of Mr. Beaubien’s first assignments in 1963 was going to Paris as part of the Expo 67 delegation to convince the Bureau International des Expositions (BIE), the body governing official world exhibitions, that the Montreal site would be ready on time.

“Beaubien remembers the BIE meeting room being so packed with people, he had to stand on a staircase, which is where he overheard two Frenchman in front of him dismissing the exhibition’s prospects with the utmost condescension. No way the Canadians could pull this one off,” Mr. Lownsbrough. Mr. Beaubien told the author: “We came back with feeling that this was what Europe was thinking of us. That was a great incentive.”

While he was in Paris he had another task: interview the woman who would receive the world leaders, from the Shah of Iran to Emperor of Japan, to the fair. That woman was Krystyne Romer, a Polish immigrant to Montreal who spoke five languages and had diplomatic experience in Paris.

Now Krystyne Griffin, she ran the diplomatic receptions at the pavilion on Île Sainte-Hélène, which Mr. Beaubien always attended as well.

“He was a global person, always in a good mood and the best PR person you could ever find,” Ms. Griffin said. Her day started at 7:30 in the morning and more than once she found Mr. Beaubien still sleeping at the VIP pavilion after working late into the night.

“Philippe was my boss for the final two years I worked at Expo 67,” said Diana Thébaud Nicholson, who worked in public relations promoting the fair starting in 1963. Among other things, she trained the first hostesses. She worked as one of his two executive assistants and helped write the final report after the fair closed. “His legacy includes a brilliant career in business and philanthropy and a much-admired nurturing of the family he adored. But for many of the older generation he will always be the flamboyant, exuberant Expo 67 Mayor of the Fair.”

Expo 67 opened in April and by the time the fair closed, more than 50 million visitors had clocked through its gates. When the Order of Canada was established that year, Mr. Beaubien was named one of its first officers.

Philippe de Gaspé Beaubien II was born in Montreal on Jan. 12, 1928, or more precisely in Outremont, the rich suburb on the other side of the mountain from downtown and an enclave of the francophone upper middle class. Philippe de Gaspé Beaubien – he was almost always referred to with all three names – was extremely proud of his family’s roots in New France. His first ancestor in Quebec arrived in 1646, and Mr. Beaubien described one of his early family members, Charles Aubert de La Chesnaye, as “America’s first millionaire.”

Mr. Beaubien’s grandfather, Louis Beaubien, founded Outremont in 1875, changing its name from Cote-Sainte-Catherine (still the name of the main road in the inner suburb). He was its mayor for 43 years. Today, Outremont is a borough in the island wide Montreal Urban Community.

He was the first of six children and in a documentary he sponsored on his life, he recalled that he was spoiled by his mother, who died when he was 12.

“As the eldest child, I had to take care of the other members of the family. It was a difficult time for me. My father wasn’t all that stable because he had lost his wife at a young age. He took solace in alcohol.”

Young Philippe was ambitious from the start. He was first in his class at his private school. He graduated from the University of Montreal. His next-door neighbour was Pierre Trudeau, who in 1953 invited him on a road trip to Boston, where Mr. Trudeau was visiting Harvard. The university intrigued the young Mr. Beaubien, who applied. He recalled that the man interviewing him for admission spent most of the time quizzing him while looking out the window at a football game.

His naysaying father warned that he would never be accepted. Wrong again.

Mr. Beaubien was shocked that professors at Harvard expected him to think on his own rather than learning by rote. On a July 4th weekend trip to Cape Cod, he chatted up a pretty waitress, Nan Bowles O’Connor, known *as Nan-b. Soon they were a couple. When he returned to Montreal, they communicated by letters. On one trip back to visit his girlfriend, Mr. Beaubien had a serious car crash and was hospitalized.

The couple married six months later, and Ms. Beaubien finished her master’s degree at McGill University.

Mr. Beaubien worked for his father’s business, but they had a falling out, and the son started Beaubien Distribution, which in five years became the largest trucking firm of its type in Canada. The main client and sponsor, General Foods, pulled its support and bought Beaubien Distribution from him.

Shortly after that, he received a call from Robert Shaw, deputy commissioner of Expo 67, offering him the job as director of operations at the World’s Fair in Montreal. He accepted right away. He worked on promoting the fair before it opened, meeting every visiting dignitary and visiting the site every day on a golf cart. Expo 67 made Philippe de Gaspé Beaubien an unblemished household name.

“After Expo I wanted to start my own company,” he said in the documentary. And after all the positive coverage from running Expo 67, he was a big name and in demand.

Power Corporation asked him to run Télémedia, which owned a string of radio stations in Quebec and Ontario. The job offer came with an option to buy 15 per cent of the company’s shares. “I saw an opportunity to have something of my own,” said Mr. Beaubien, whose ambition was to build on his family’s entrepreneurial record.

He soon had an even bigger opportunity. Paul Desmarais, the head of Power Corporation, walked into his office with an offer he couldn’t refuse. He asked Mr. Beaubien if he would like to make an offer to buy Télémedia. “Make me an offer, and out he walked.”

“Would he be interested? He jumped at the opportunity,” his wife said.

The trouble was that in 1970, Télémedia was losing money. Mr. Beaubien managed to put together the financing but then he set about making his company profitable, which didn’t make him popular with all his employees, he said.

“I worked like crazy,” he said. It took five years to make it profitable.

But in 1970, one of his radio stations, CKAC in Montreal, became part of what became known as the October Crisis. The Front de Libération du Québec (FLQ) sent its demands and manifesto to the radio station. The FLQ revolutionaries helped make CKAC a raging success.

“We were the first French-speaking Canadian media company to grow in English-speaking Canada,” Mr. Beaubien said. He also expanded into print, including the Canadian edition of TV Guide, which was a huge success, with its French-language counterpart, TV Hebdo.

By the year 2000, Télémedia owned 26 radio stations, 17 magazines and 24 weekly newspapers across Canada in both French and English.

Mr. Beaubien was always in demand as the face of worthy organizations. In 1971, his old next-door neighbour, Pierre Trudeau, was prime minister and asked Mr. Beaubien to become chair of the Canadian Council on Fitness and Sports, which became ParticipACTION, a Canada-wide program promoting physical activity. Perhaps its most famous campaign was the ad that compared the fitness of a 30-year-old Canadian to that of a 60-year-old Swede.

In the 1980s, Mr. Beaubien joined with Ted Rogers and Sam Belzberg to win a licence from the CRTC to operate Cantel, a cellular network to compete with Bell. However, his board said the company was operating in too many directions. Télémedia gave up on the cellphone business.

At the age of 60, Mr. Beaubien gave control of the company to his three children. In 2000 and 2002, Télémedia sold off its radio stations, magazines and other assets to several other companies. In 2024, Canadian Business magazine said the family was worth $740 million.

After Mr. Beaubien left Télémedia, he and his wife set up the de Gaspé Beaubien Foundation, which has a division that advises family businesses on succession, among other things.

One of his two sons commented on his father’s legacy.

“My father’s leadership helped shape modern Quebec and Canada, and his influence was felt well beyond our borders. He leaves behind not only a legacy of visionary accomplishments in business and philanthropy, but also a lifetime of unforgettable memories for us, his family. He was a devoted family man whose boundless energy and passion touched everything he built – and everyone he met. He has left an indelible mark on all who knew him,” François de Gaspé Beaubien said.

Mr. Beaubien received many honours and accolades throughout his life, including honorary doctorates from York University, the University of Montreal, and UBC. He was inducted into the Canadian Broadcast Hall of Fame and the Canadian Business Hall of Fame.