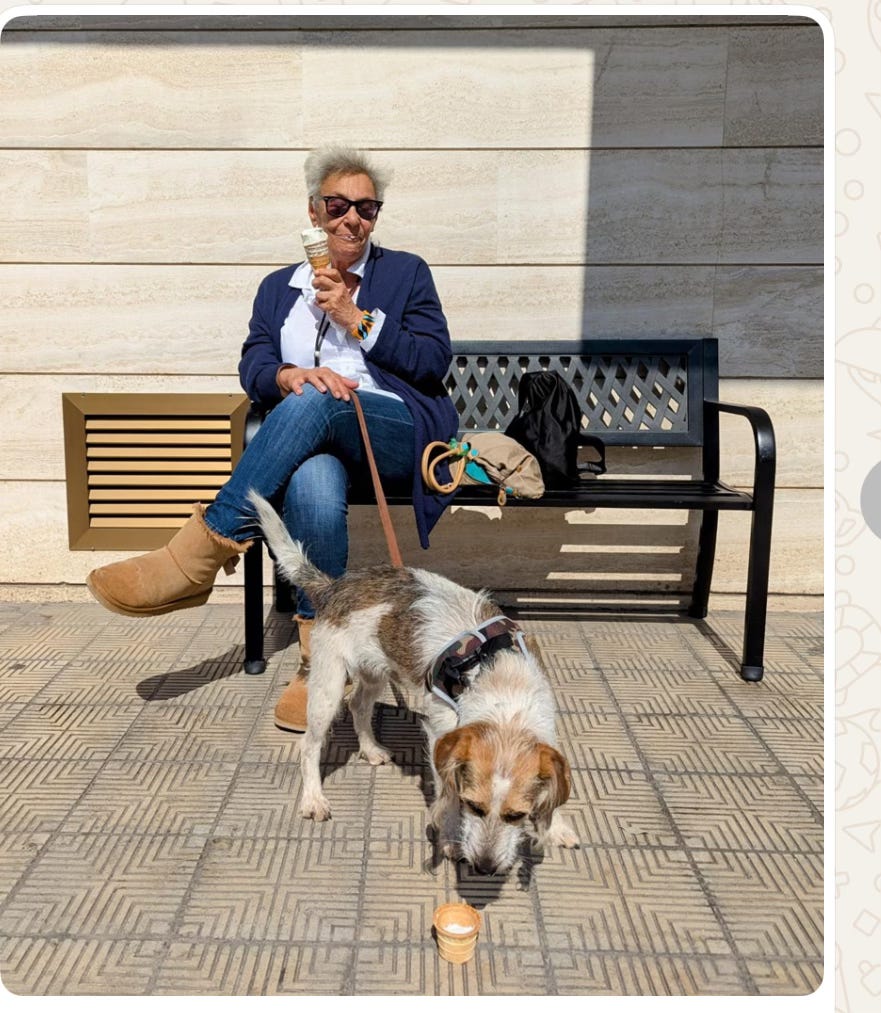

Dogs in Italy

Spoiled

Dogs are everywhere. In restaurants, in caffes and in the street. Unlike Canada, where there seems to be an I hate dogs mentality. The dog in the scene above, hiding under the chair, would have been banned in my favourite caffe in Toronto. City rules. Dogs aren’t allowed in restaurants or outdoor terraces, though some places let people cheat.

Above is my friend Maria Pia and Gramsci in Puglia. At the local gelato store, people pay but dogs eat for free,

I had never seen this breed before, though it looks remarkably like my Sealyham, Poppy. This is a Broken Jack Russel. There are several in Camogli. When I said it must be a crossbreed, the owner was quite shirty and assured me it was a purebred.

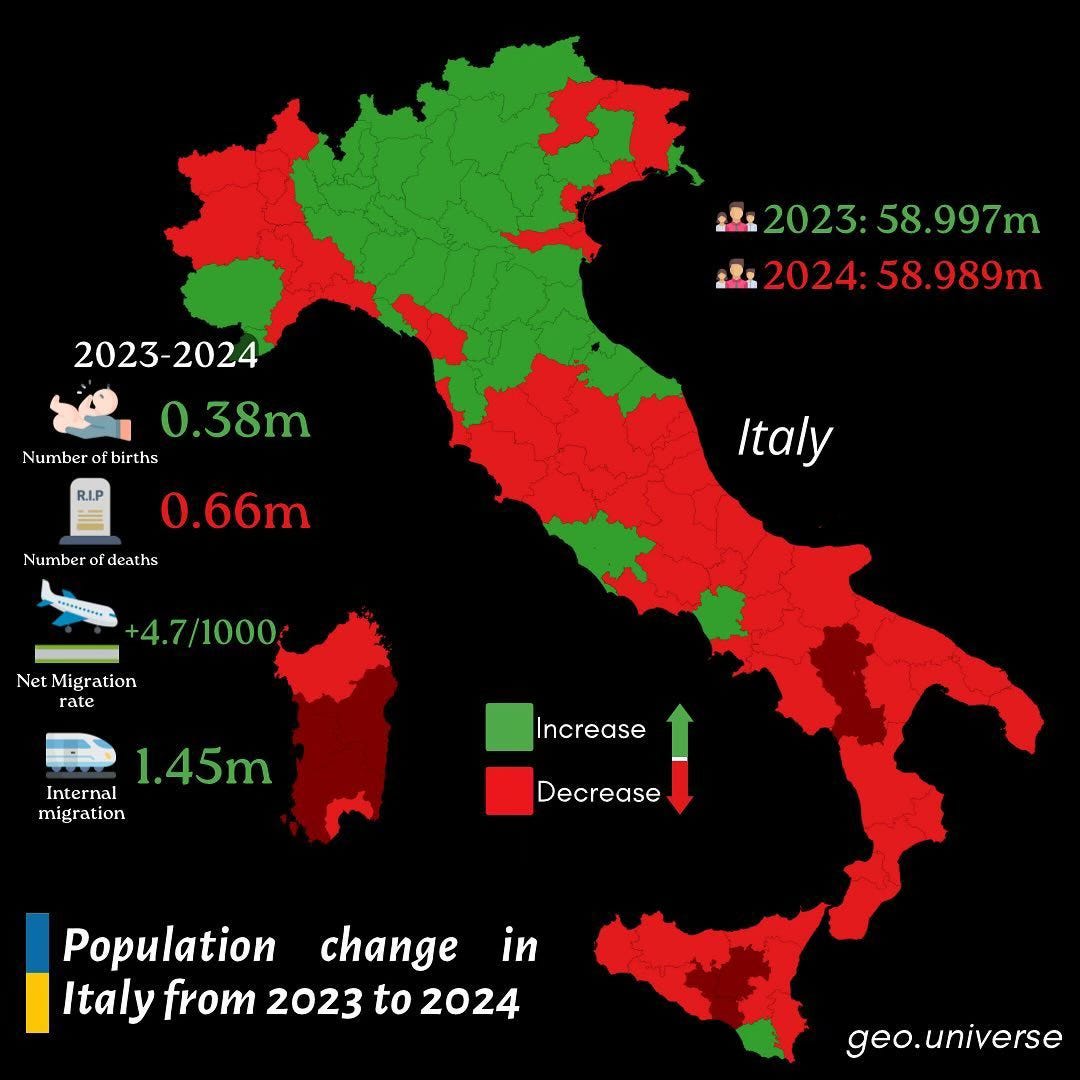

Italian Demographics

There are children everywhere in Camogli, the town where we are staying. They race up and down the Lungo Mare on scooters and play soccer on a small piece of pavement. But it is not the story for Italy. It is the oldest country in Europe.

One person in four in Italy is 65 or older; there are 23,000 people who are a hundred or older. Ten years ago the population of Italy was more than 60-million, today it is 58.9-million. Politicians plead for more births, but it isn’t happening.

Where Italians Live

Where Italians are Being Born

The Silly Season: What to Wear?

British Summer is taken up with `events’ but not the kind PM Harold Macmillan spoke of “Events, dear boy, events”, when asked what shakes governments, but the frivolous bits of life from the Chelsea Flower Show to the Henley Regatta.

Royal Ascot. The racing day is the peak of the Season.

It is celebrated in a rather good cover from Country Life.

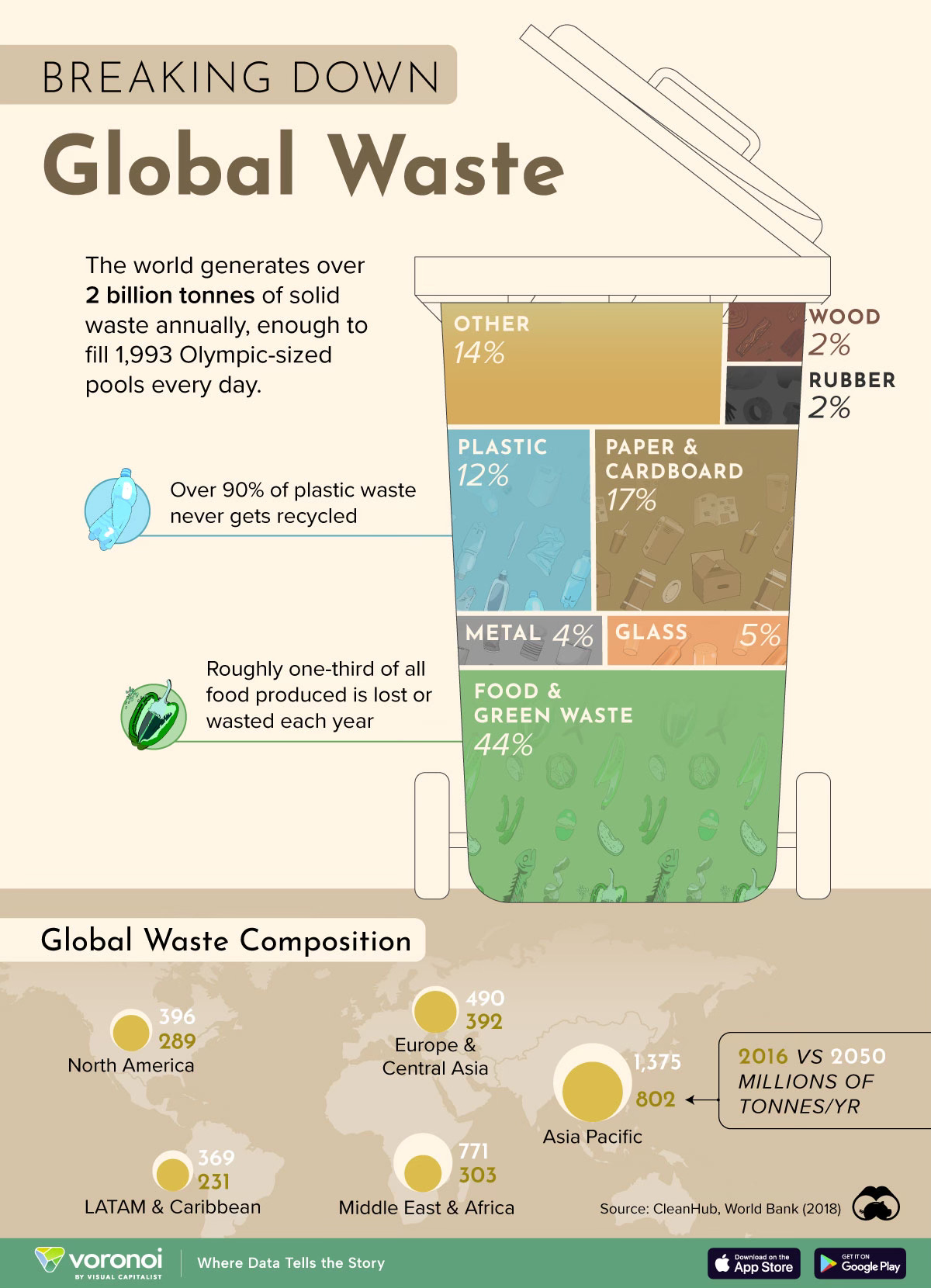

What We Throw Away

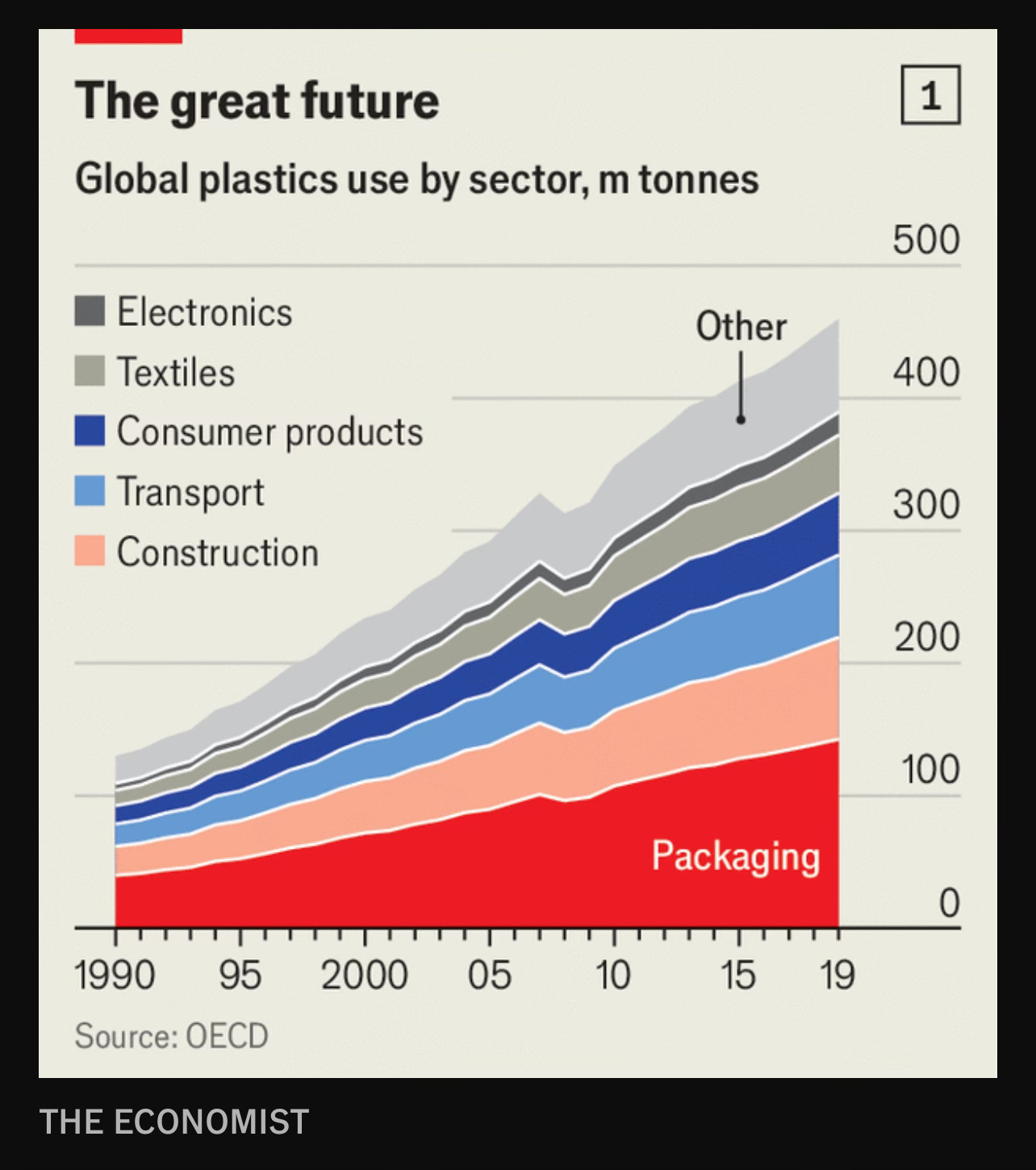

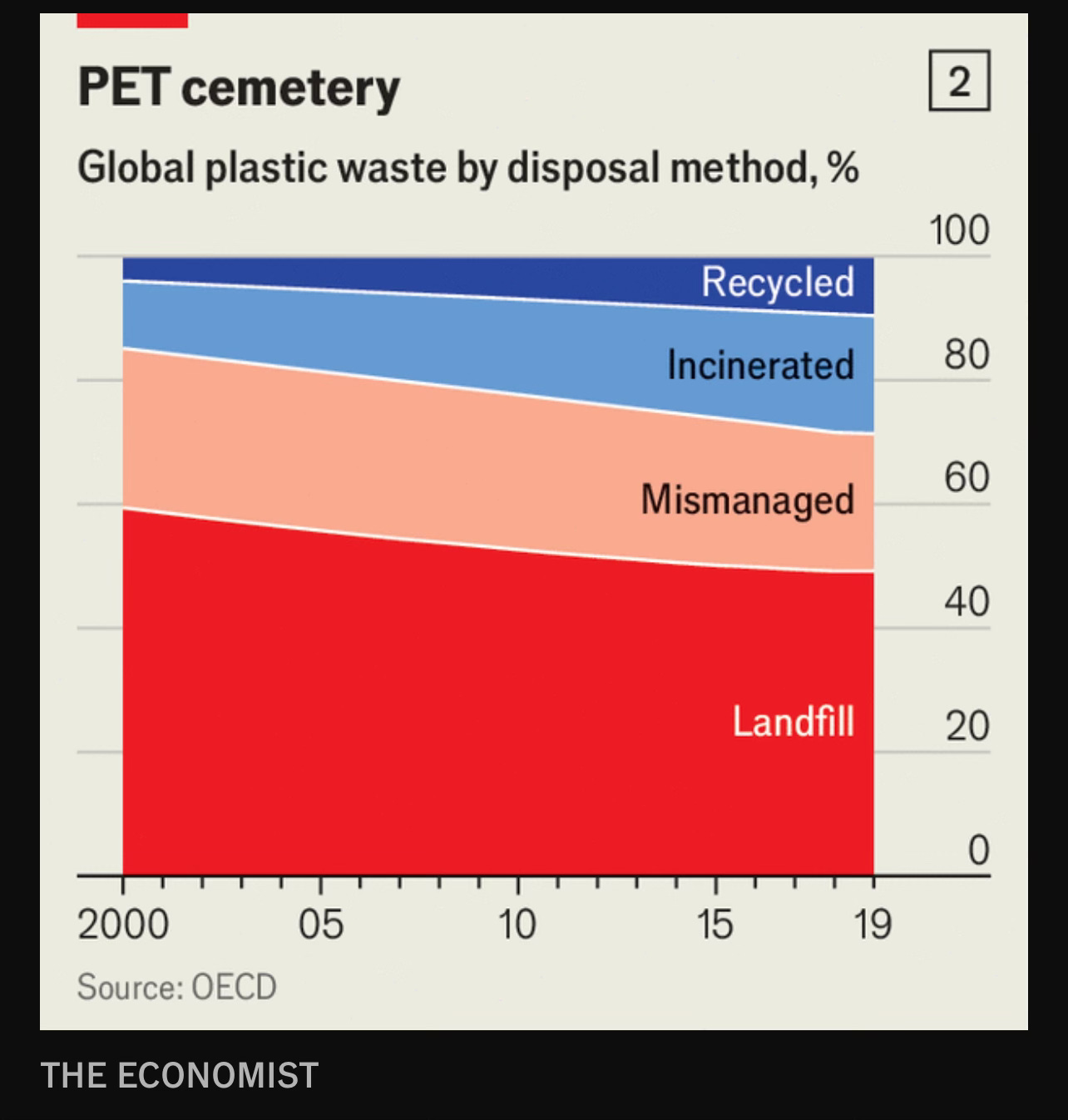

In the modern world we are programmed to think all plastics are bad. In Canada plastic cutlery has been replaced by wooden forks, spoons and knives. As an article in The Economist points out, plastic replacements use a lot more energy to produce.: “A one litre plastic bottle weighs 5% as much as a glass one; plastic packaging thus reduces shipping costs and emissions.” The Economist is all in on Climate Change.

The Economist produced two charts, one on where plastic is used, the other showing it does think plastic waste is a problem.

The article suggests more recycling and using landfill. I can tell you the landfill solution wouldn’t go over well with most of the people I know.

Dumb and Dumber

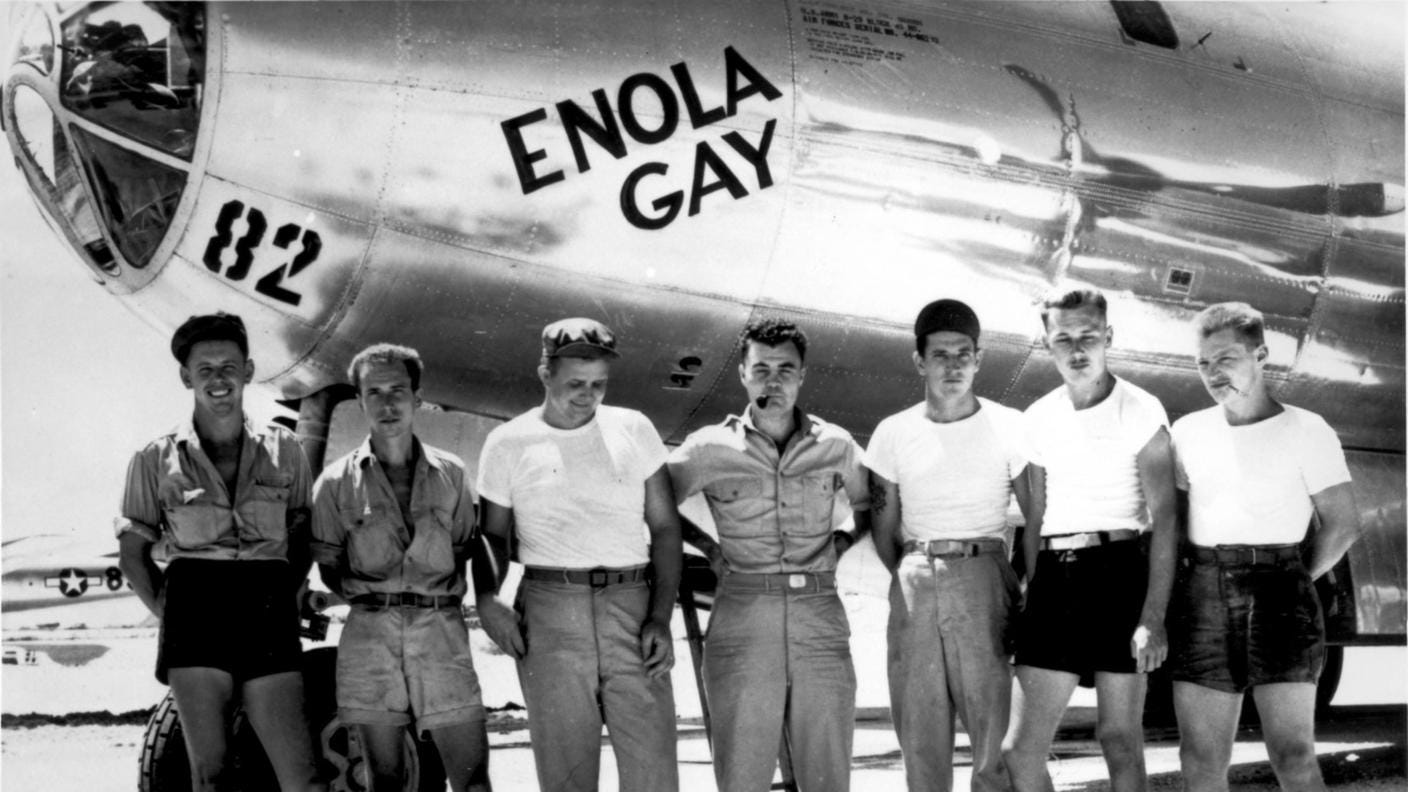

Pete Hesgeth, still Defence Secretary at this writing, is trying to get rid of any traces of Diversity. Books have been banned and names and photos placed on the verboten list, including this one.

Oops. The word Gay is on Enola Gay, the B-29 bomber that dropped the Atomic Bomb. It comes from Enola Gay Tibbets, the mother of the pilot Colonel Paul Tibbets.

Essay of the Week

These are the first two chapters of a book on Sam Ciccolini, another Italian immigrant who made it in Canada. Sam is an outgoing, self-confident man and a super salesman, running Masters Insurance with other members of his family. It is said if you take an aerial photograph of the Greater Toronto area, the Ciccolinis insure one site in three. Sam is also an amazing community organizer, putting together dozens of events a year. For a man who was in a seminary as a boy, he is still a religious Catholic.

Chapter 1

Early Life in Italy

Salvatore Giovanni Ciccolini was born on July 3, 1944, in the village of Pescosolido in the foothills of the Apennine Region southeast of Rome. Pasquale and Filomena (Sarracini) Ciccolini had six sons, one of whom died in 1939.

Pescosolido is not prime farming country; it is rough terrain, with fields of wheat and corn framing the olive groves and vineyards on the rocky hills. The scenery is spectacular, sitting on the edge of the Abruzzi National Park; so special it is designated as an area of natural beauty by the European Union.

Sam was born the last year of the Second World War and July 1944 was the peak of the fighting in Italy, in his region in particular. The mountains made ideal defensive positions for the German Army. The famous Battle of Monte Cassino took place nearby and the Ciccolini family watched as aircraft from the Allied side made their final bombing runs to attack the monastery that they mistakenly thought was a fortified German position. After the war there were a lot of unexploded bombs in the area, some in the Ciccolini’s own village.

Pasquale Ciccolini, Sam’s father, was a soldier in the Italian army. When he returned home he found his country, and in particular his village and region, even poorer than before. There were shortages of everything and foreign armies, British and American, enforced the peace. The country was often near civil war as partisans, many of them Communists, exacted rough justice on their former enemies, real and imagined.

Pasquale eked out a living owning and driving the only taxi in the area, a Balilla*, a pre-war sedan noted for its relative size if not its beauty. “He could sit seven or eight people inside and then about 14 hanging to the top of the car. It was like one of those films from India,” recalls Sam Ciccolini.

This may be an exaggeration of a childhood memory. The Balilla was the nickname for a Fiat 508 and even in the four-door version it was relatively small by today’s standards, though it dwarfed most tiny Italian cars. It was big enough to carry goats and sheep on occasion and in 1956, driven by an uncle who had taken over the taxi business, carried four members of the Ciccolini family the 140 kilometres from their village to the port at Naples.

*Balilla" was the nickname of Giovanni Battista Perasso, a boy from Genoa who in 1746 threw stones at an Austrian officer in protest over the Austrian military occupation, starting a revolt.

The Frosinone province in the Lazio region was one of the poorest in Italy. Pasquale’s father died before Sam was born and his mother ran a tiny bar in the middle of the village of Pescosolido.

Sam’s branch of the Ciccolini family fared better than most since they owned some land. Filomena’s father had spent a decade working in Detroit, Michigan, and returned from the United States a relatively rich man. He bought farmland in Pescosolido; Sam and his brother Max estimate it would have been as much as 50 hectares, about 120 acres. Some of it was deeded to Filomena, even though her father objected to her marriage to the poor Pasquale. His objections were so strong he refused to attend their wedding. Pasquale was a quiet handsome man and Filomena loved him; the marriage took place without her father’s approval.

Sam, his brothers, and his parents lived in a house squeezed between his grandfather and an uncle. There were animals downstairs, some cows, a donkey, and a few pigs. Every Christmas two of the pigs would be slaughtered in the barnyard, providing meat for the year. There was corn and wheat in the fields, but the valuable wheat was sold to earn cash and the family ate corn bread.

“We lived quite modestly to poor. We never went without food but everything else was rationed, as it was for everyone else in the village,” says Sam. The Ciccolini boys were also well dressed as Filomena was an accomplished seamstress. Like most rural Italian women of her generation she only went to school until grade three, but she was a clever and ambitious woman, the matriarch of the family and the driving force behind the future success of her sons.

Primary school in rural Italy ran from early morning until one in the afternoon. Then the children would go home to help their parents-- in Sam Ciccolini’s case, helping to tend the fields and animals. Though they were poor – Sam never wore new shoes, always hand-me-downs, until he came to Canada – there was a warm family life. That warmth can be seen in the character of Sam Ciccolini and his brothers to this day.

Chapter 2

The Seminary

Italy is still a Catholic country but in the 1950s it was even more fervent, harbouring a faith of such intensity that was matched in just a few other places in the Christian world, perhaps in Poland, Ireland, and Quebec.

As the second youngest of six sons Sam Ciccolini was chosen for the priesthood. In 1952, at the age of nine, he was sent from his village of Pescosolido down the hill to a seminary in the cathedral town of Sora, six long kilometres from his home. Putting a nine-year-old into to a seminary may seem startling to some people, but no more than a young boy being sent to boarding school on a scholarship.

“In our area there was a lot of poverty so if you were picked as one of the ones who were a little brighter, you were sent to the seminary, because your parents couldn’t afford to send you,” says Sam. “One of the reasons I went was we have a history of priests in our family. The rector at the seminary, just before I entered, was one of my father’s cousins and the priest in the town, was a second cousin. He’s still a priest and he’s 96 years old.”

Sam Ciccolini remembers his three years in the seminary with fondness. It was perhaps the most intense period of learning in his life, and certainly much more rigorous than what he would later face at Clinton Public School or Harbord Collegiate in Toronto. At the age of 11 he could speak and write Latin, something few if any high-school Latin teachers could match.

There were about 20 boys in Sam’s class at the seminary. Days started at 6:30. The boys would rise, wash and bathe in cold water--there was only one bathtub, no showers--then they would put on their long cassock that had many buttons from the neck to the knees. The boys would also wear a biretta, a black clerical hat. They were dressed like little priests, as they expected to be dressed for the rest of their lives.

Mass was at 7 a.m. without having had breakfast since they would have to fast before taking communion. Then at 7:30 came the first meal of the day, almost always a brioche and coffee, though Sam says that as a young boy he didn’t like coffee.

Class would start at 8:00 o’clock. The study was rigorous. The teachers, all priests, ruled with strict discipline though there was little if any physical punishment; the novices knew their place and that obedience was their lot in life. It was not a totally cloistered life: they were allowed walks in the street, they could talk with each other, and there were long periods of play, extended recesses where boys could be boys.

“The priests believed in physical activity and health,” said Sam, who was athletic as a boy and an adult. “The one thing that the seminary taught you was discipline. It’s a great trait because because then you’re not scared of anything. It gives you a lot of self confidence and I think you’re better off than someone who is timid.”

The young seminarian was certainly not timid; his personality was already fully formed and young Sam Ciccolini exhibited the self confidence and exuberance that sometimes got him into a bit of trouble.

“Sam was in the seminary in Sora and he was always being reprimanded because he always wanted to do everything and sometimes he would even get into problems,” remembered his mother, Filomena Ciccolini, in an interview in 2003 for a video tribute to Sam.

Sam left the seminary on November 5, 1956, and within a week was sailing to his new life in Canada. But the lessons he learned there stayed with him for life. It may even account for his self confidence and ability to speak with ease in front of large crowds. It certainly implanted a solid value system.

“I think my life, my faith, and the way we comport ourselves even when we lost our daughter comes from my upbringing in the seminary and it (his Catholic faith) is a bit of a soft spot in my heart,” says Sam.