Luxury Stocks Drop; Work From Home Chop; China # 1 in Wind and Coal; A Mouse Forced Landing and a Cancer Charity Star

September 23, 2024 Volume 5 # 15

Interest Rates Down, Stock Markets Up

The Federal Reserve cut rates by half a point. Stocks went nuts. But not all stocks.

Luxury Stocks Tank

Headline in Barron’s which reports that shares of Burberry are down 57% for the year, Kering (owner of Gucci) off 43% and mighty LVMH down 18.6$. LVMH is Louis Vuitton, Moet Hennessy and others. It has taken its controllong shareholder Bernard Arnault from richest person in the world down to number five.

The reason: even rich people balk at rising prices for show off stuff. This Gucci running shoe for instance is $1415.

From Barron’s:

“There has been some fallout from people who have decided, ‘I’m just not going to buy anymore because this is getting ridiculous,’ ” says Gabriella Santaniello, founder and CEO of retail consulting firm A Line Partners. “You can’t say the price is higher due to the artistry of the product when it has nearly doubled in a few years.”

Amazon Says Back to The Office

Jeff Bezos may be off on his yacht but Andy Jassy, the man who is running Amazon day-to-day, sent out a memo to its office workers saying all hands on deck.

The work dream that took off with Covid, may be over. ‘The Work From Home Free-for-All Is Coming to an End. If you thought your two days a week at home were safe, think again,” says the Wall Street Journal.

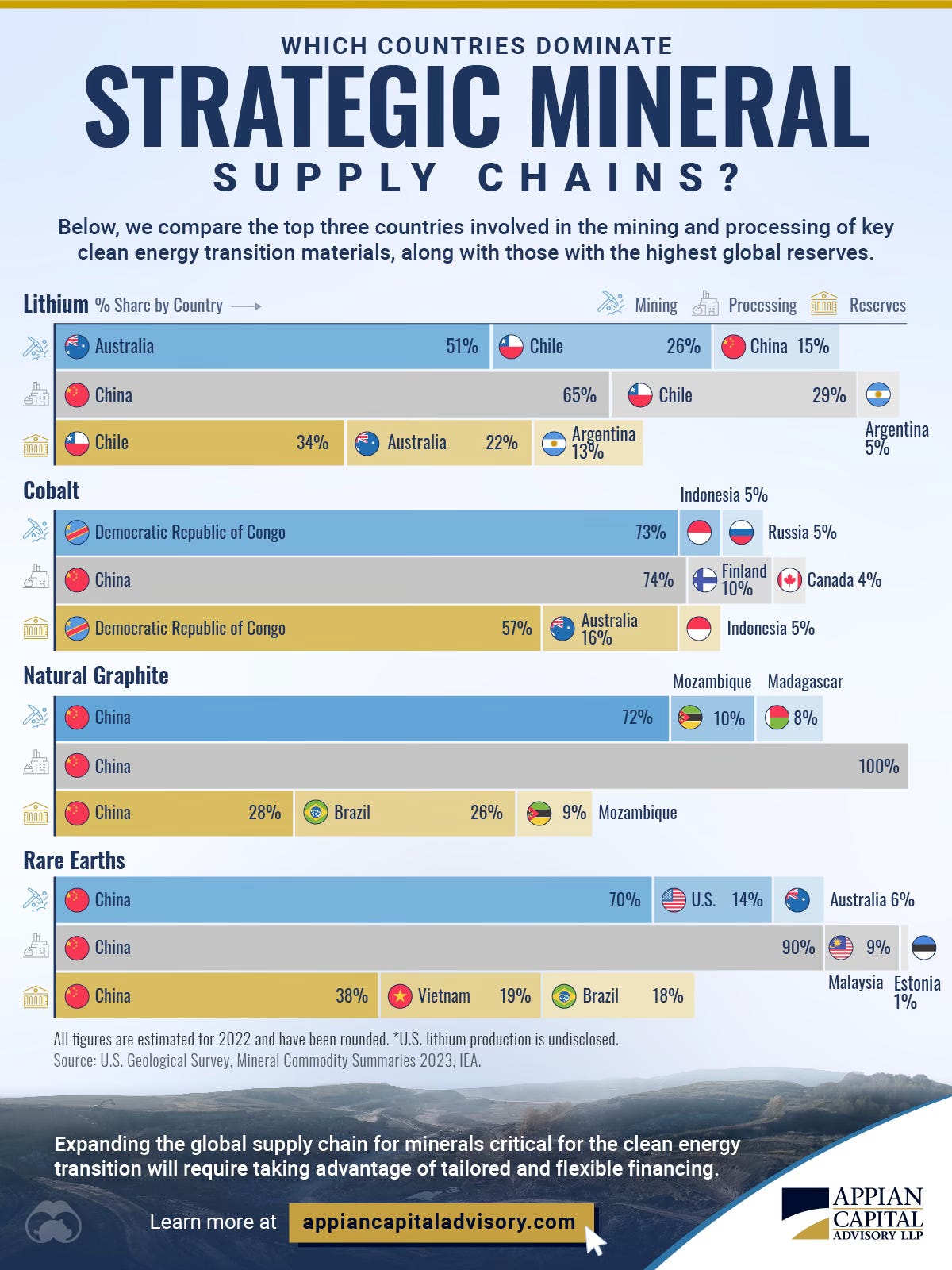

Where the Metals Are

These are the metals that are used in things like cell phones and computers and, as the chart says, are necessary for the dreams of a green future. On the postive side, many countries, Canada and the United States among them, are waking up to the need to allow mining of these minerals. Canada already produces cobalt, much of it at a remote mine in Voisey’s Bay in Labrador.

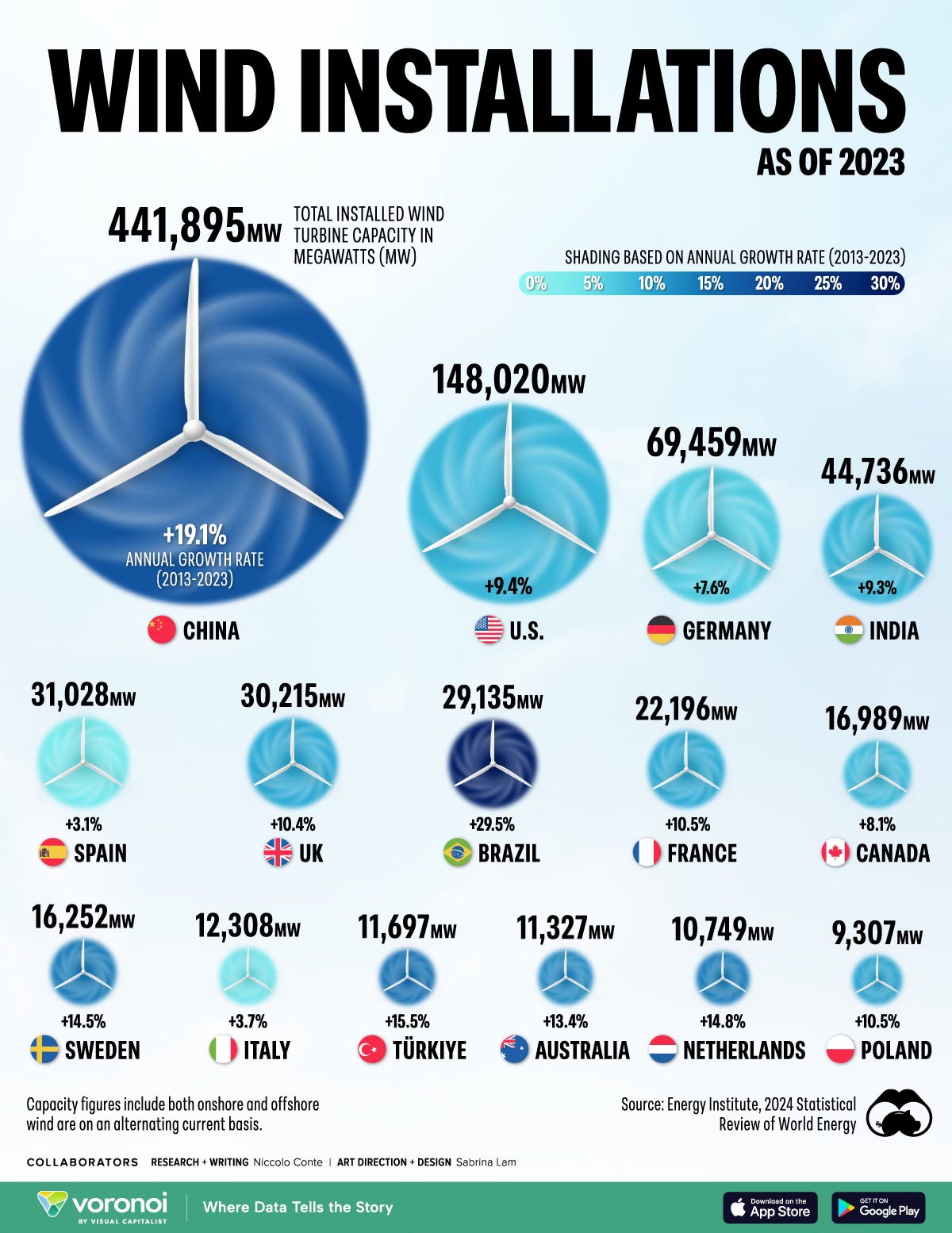

Where the Windmills Blow

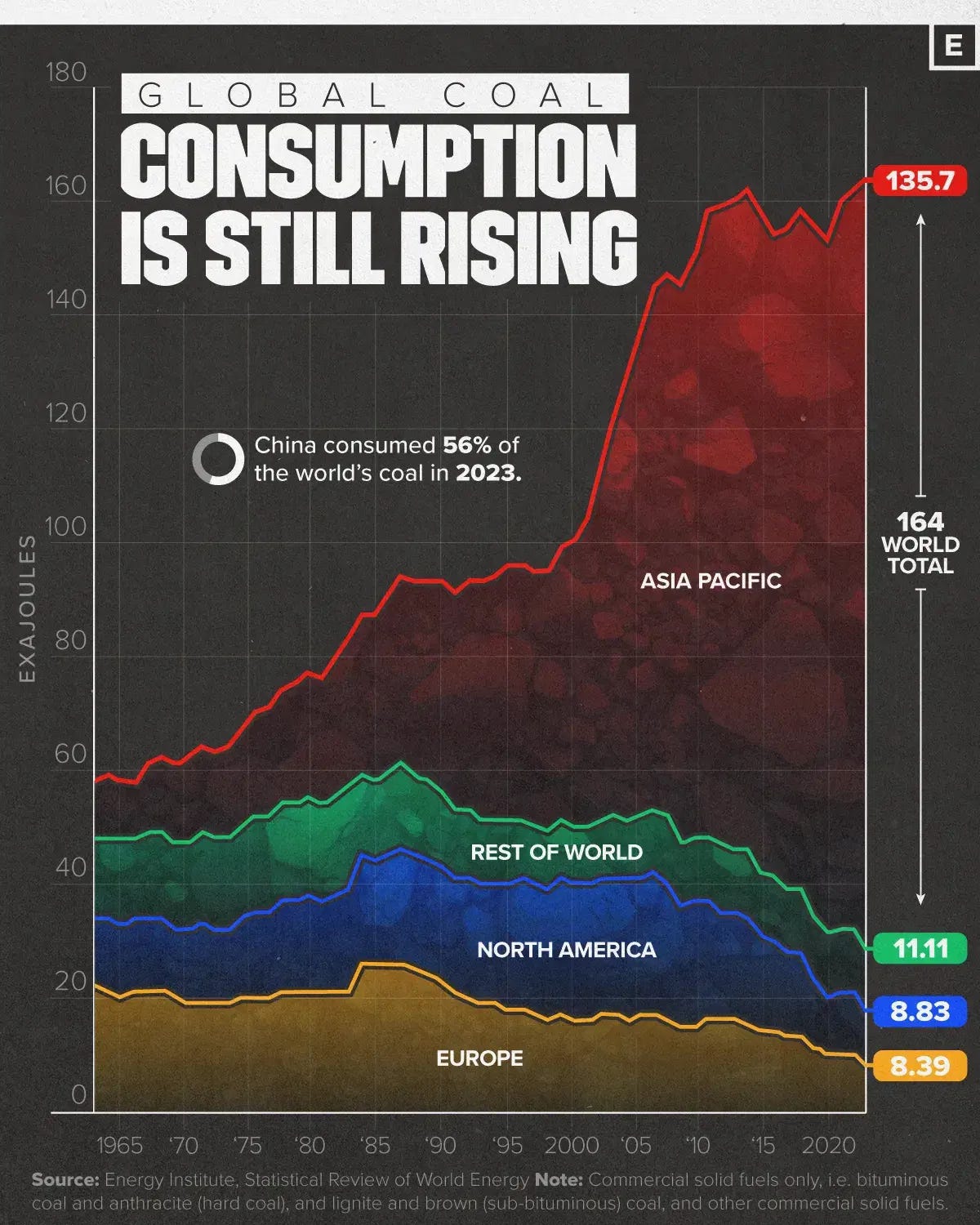

But Before You Get Too Excited…

Goody-two shoes Canada and Europe cut coal while China and India smoke away.

The Real Thing This Year

This photo in Jiangxi, China on June 30, 2024. Chimneys pour out the smoke at Jiujiang Power Generation Company, an energy conglomerate on the Yangtze River.

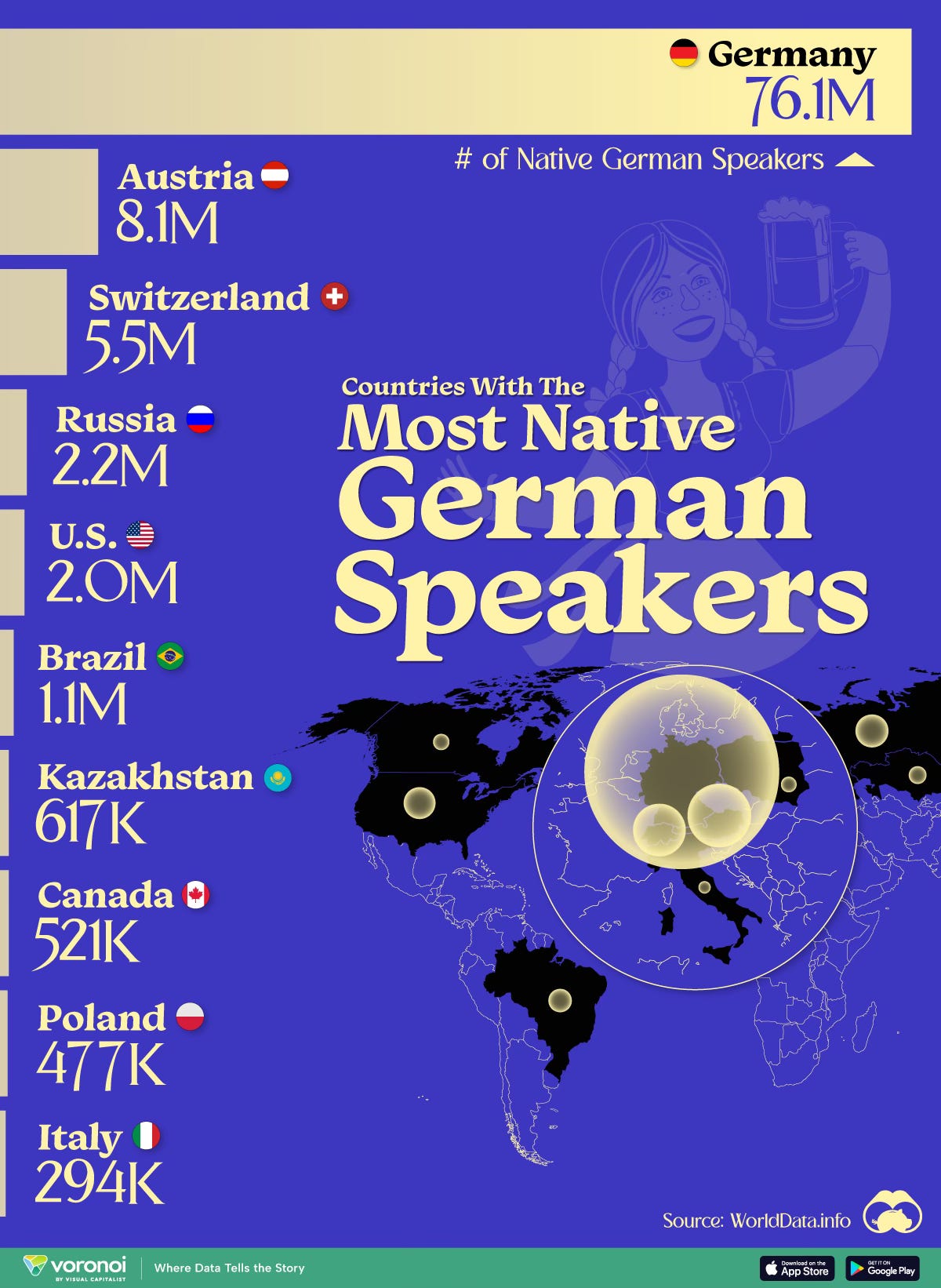

German Speakers

There were more German speakers in the world in 1914 than there are today, for obvious reasons. This chart misses the German speakers in Argentina and Brazil.

A Mouse in the House

A mouse jumped out of a passneger’s food tray on an SAS flight, reports the website, Simple Flying. The plane, an Airbus 320neo, was forced to divert to Copenhagen. Seems a bit of an over reaction. Is there a no mouse rule in international aviation?

All New Material

The Essay of the Week is almost always an obit I have written, or a chapter from one of my books. I figure there are more than a million words on my computer so I should never run out of material. However, a long time subscriber complianed recently that I had re-run an obituary. Well this week I discovered a treasure trove of new material, which will start to run next week. In reparing the second computer in our household there was a folder of many stories than are older than the ones on my hard drive and cloud memory. This week’s essay is the latest obit I wrote for the Globe and Mail.

Essay of the Week

When Lynda Turner was first diagnosed with breast cancer in 1990, she received a visit at her room at Montreal’s Royal Victoria Hospital from a woman on crutches who wanted to know if there was anything she could do. That woman was Sheila Kussner, who had lost her leg as a teenager to a Terry Fox like cancer, and who spent her adult life trying to bring hope to people with cancer.

Sheila Kussner, who died just two weeks shy of her 92nd birthday, started an organization called Hope and Cope, which did what its title said for cancer patients as well as raising tens of millions of dollars for cancer treatment. She and others were instrumental in starting an oncology department at McGill University.

She became a phenomenal fund raiser, spending her time and her own limited resources getting the funds needed for her many projects.

“Sheila would call me and say this is the last time, but we’re so close and we need just another thousand dollars,” said Kerrigan Turner, whose wife Lynda died of breast cancer in 1994. “She was a dynamic, selfless person. You couldn’t say no to her.”

Sheila Golden was born in Montreal on August 24, 1932. Her father Jack Golden was a successful insurance salesman, the third generation of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe and the first in his family to break into the prosperous middle class. Early on the family moved from the working-class Mile End Jewish district to a semi-detached house in nearby Outremont.

When Sheila Golden was 12 years old, she was chased by a boy she knew and got her foot tangled in the spokes of his bicycle. Her ankle needed surgery, but it led to the discovery of a rare cancer in her knee. One doctor after another told Sheila and her mother that unless the leg was amputated above the knee, the cancer would spread and kill her.

The pretty teenager refused to accept the prospect of losing her leg.

“I said to my parents, `I’m sorry, I’m not having my leg amputated. That will be the end of my life’,” she recalled in her biography: Repairing the World, Sheila Kussner and the Power of Empathy.

More than a year after her initial diagnosis, a doctor quietly convinced her to go ahead with the amputation, pointing out what a hardship her death would be to her parents. She lost her leg just before her 14th birthday. Most people with that type of cancer—osteosarcoma-- don’t survive long; Sheila lived for another 77 years. She wore an artificial leg, and it showed when she tried to climb stairs. One boyfriend asked her what was wrong. “He doesn’t know,” she recalled. She told him about her leg, and he never asked her out again.

Sheila Golden married Marvyn Kussner in her early 20s and the couple raised two children. Ms. Kussner was involved in charities early on but when her husband was diagnosed with Lymphoma at the age of 43, she moved into high gear. It was in 1981 when she founded the help group which she named Hope and Cope. She said she came up with the name after speaking with a young woman with cancer who said to her: “How can I cope, when there is no hope.”

It started as a volunteer organization, today Hope and Cope has 15 full time and part time staff and about 350 volunteers, almost all of them cancer survivors.

“That was Sheila’s model that there was a wisdom that came from having lived the experience of cancer and care giving and the experience of loss that made it very powerful to accompany somebody through that journey,” said Suzanne O’Brien, president of Hope and Cope. “Sheila intuitively understood from her own experience that talking to somebody else who had that same circumstance could be very powerful in offering hope that you too could get through this.”

Ms. Kussner received honorary doctorates from both McGill and the Universite de Montreal because of her contribution to cancer care. Before she was involved, there was not a separate oncology department at McGill.

“We ended up with a new department of oncology but, of course, with no budget. If you wanted to do something new you either took money away from existing departments or you went out and raised new money.” says Dr. Richard Cruess, who was dean of Medicine at McGill for 14 years. “That is where Sheila came in, she was one of the most skilled and devoted fundraisers I ever saw. We raised somewhere between twenty-five and thirty million dollars over a six- or eight-year period for this department of oncology.”

Along with the big things, such as funding cancer treatment and research, Ms. Kussner dealt with personal problems, such as where to buy the best wigs for patients who lost their hair during chemotherapy.

Sheila Kussner never stopped networking. She had written lists of people she wanted to stay in touch with: she used an old flip phone and shunned email. She spent her own money— unlike the donors she sought out, she was not that rich a woman—to send people gifts, which she often delivered herself. “She was very generous with her time and always remembered our wedding anniversary. She called just two weeks ago,” said Dr. Carolyn Freeman, who was chair of radiation oncology at McGill and a major innovator in that world.

Dr. Cruess, who is an orthopedic surgeon, said Ms. Kussner was in constant pain from her amputation, pain which he said got worse as she grew older.

“For people with prostheses as you get older you lose tissue under the skin so she had a terrible time for most of her adult life which she absolutely and totally ignored. She had to be in pain a lot of the time, but I never heard her complain,” said Dr. Cruess.

“Sheila probably raised over fifty million dollars for cancer support at Hope & Cope, at McGill and at the hospital,” said Ms. O’Brien. “She was an absolute force, passionate and committed but every donation it could be ten dollars or a hundred or a thousand or a hundred thousand, they were all the same to her. She went after the big donations, but she valued the smaller gifts as well. If someone could give a hundred dollars today, maybe that future donor might, as their circumstances change, have the capacity to give more.”

It takes a certain kind of person to be a successful fund raiser. Ms. Kussner told the Globe’s Eric Andrew Gee that when it comes to fundraising: “There’s no technique – you just have to know the donor.”

But her colleagues say knowing who has the money and the inclination to give was a big part of how Sheila Kussner operated.

“Her technique was really to get to know the other person. She valued relationships and she was not a cold call kind of a fundraiser,” said Ms. O’Brien. “She made it her business to get to know who they were and what they valued but the secret to her success was that she knew the capacity of her giver. She never asked for more than what was their capacity to give although she did put people on the spot. She did her homework, and she valued the relationship,”

One of her contacts was Pierre Trudeau when he was prime minister and in retirement. The two would often have lunch at the garden in the Ritz Carlton Hotel. She always paid the bill. “He was cheap.” Ms. Kussner said. “But I loved him, he was a great man.”

Ms. Kussner knew a man who was depressed after he had been crippled by prostate cancer. She brought Alex Issenman to a lunch where Mr. Trudeau was speaking, introduced him to the prime minister, a gesture that lifted the cancer patient’s spirits.

There were some amusing incidents in her fundraising life.

“We set up a fundraising committee that used to meet in my office and Sheila would arrive at the committee meeting usually with a caterer who would come with some champagne and smoked salmon,” recalled Dr. Cruess, the dean of Medicine. “One of the most hilarious experiences was we were sitting around and people had finished their glass of champagne and Sheila said, “Dean, serve more champagne” and I jumped up and served more champagne and the waiter burst out laughing. The waiter’s name was Dean. I jumped up because I would never have dreamt of not doing what Sheila had suggested.”

Along with her honorary degrees, Sheila Kussner was named a Member of the Order of Canada in 1983 and promoted to Officer in 1995. “She is well known for Hope and Cope, a support programme of international fame, which she founded for cancer patients and their families at the Jewish General Hospital, Montreal,” read the citation. She was also an Officer of the Order of Quebec, and Commander of the Order of Montreal and the recipient of many awards from cancer societies and other groups in Canada and the United States.

She is survived by her two daughters, Janice Kussner and Joanne Kussner-Leopold and two grandchildren.