March 14, 2022

March 14, 2022 Volume 2 # 41

All at Sea

Russian oil tankers are desperate to find a place to unload their cargo and in most cases are stuck at sea, according to the publication Oilprice.com.

The Russian state oil tanker company, Sovcomflot, has as many as nine of these tankers off North America and Europe, according to Oilprice.com writer, Tsvetana Paraskova. She reports the Sovcomflot owns 110 tankers, 52 of the Alfamaxes. She reports that:

“Many Western countries and companies are not risking touching Russia-linked crude shipped by Sovcomflot, which is majority held by the Russian government.”

An Aframax tanker carries between 500,000 and 800,000 barrels of oil, though it is in fact a mid-sized oil tanker. Its advantage is that it can unload at most ports where much larger tankers sometimes cannot.

Inflation and War

American inflation running at 7.9%, the highest in 40 years. The Russian war in Ukraine is driving up prices, especially oil, wheat and fertilizer.

It’s also domestic: the price of used cars and trucks was the biggest mover: up 40%. Same story in Canada. Every day I receive the list of used Teslas available across the country. A 2015 Model S is listed for $68,000, more than it was worth new.

The rising price of gasoline is increasing demand for used electric vehicles. The wait time can be more than year for some electric cars.

Nickel is used in electric car batteries, and in munitions. Russia is a huge producer. Nickel futures were up 174% in just two days, such a huge move that the London Metal Exchange shut down trading.

War and Famine

Russia and Ukraine are two of the world’s major producers and exporters of wheat. As you can see on the chart below they are the number one and number three suppliers of wheat to Africa. A prolonged war will lead to shortages, and the price of wheat — up 34% so far this month— is already making it unaffordable for many buyers in Africa.

Vladimir: Why sit so far away?

The Kremlin explained it is for `epidemiological measures’. The Daily Telegraph running a speculative piece a few days ago saying Putin is immune compromised. It went on to speculate his shaking hand may indicate Parkinson’s Disease. The Telegraph said his puffy face is not healthy and that he is a sick man.

The Russian leader has managed to make his people poorer, and is alienating the sub-Oligarch upper middle class that can’t buy `stuff’ like jeans and iPhones. Putin has managed to make Russians pariahs; they are the new Afrikaners.

The Russia that Putin dreams of:

The USSR at the peak of its power and what it lost.

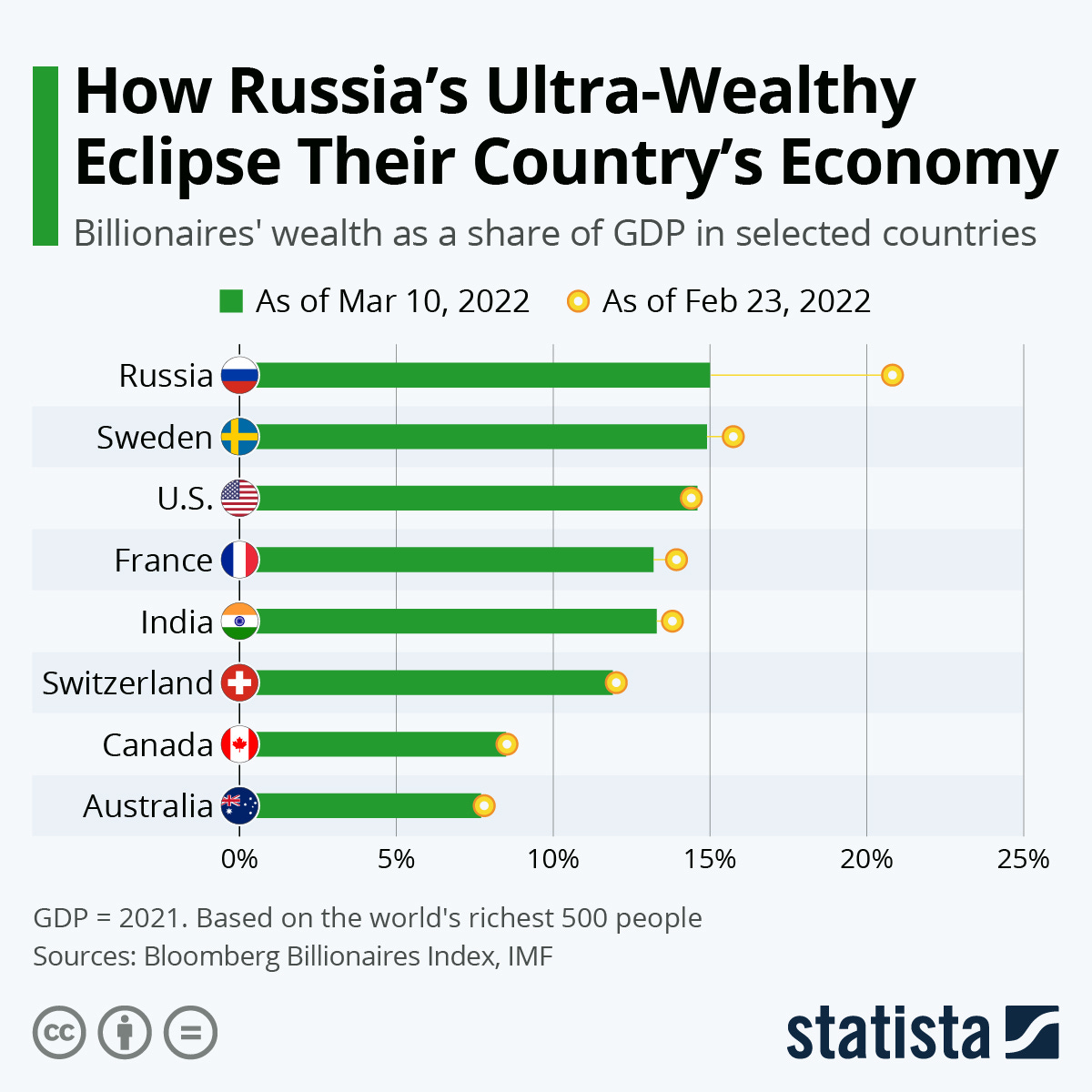

The rich get poorer: and not just in Russia

Art from a subscriber in France. Open to interpretation.

China and the war

The general view is that China is backing Russia.

However, a Chinese think tank, writes this week that Russia has failed and can’t win, even if it occupies Ukraine.

Here is how its starts. There is a link to the entire report below.

“The Russo-Ukrainian War is the most severe geopolitical conflict since World War II and will result in far greater global consequences than September 11 attacks. At this critical moment, China needs to accurately analyze and assess the direction of the war and its potential impact on the international landscape. At the same time, in order to strive for a relatively favorable external environment, China needs to respond flexibly and make strategic choices that conform to its long-term interests.

Russia’s ‘special military operation’ against Ukraine has caused great controvsery in China, with its supporters and opponents being divided into two implacably opposing sides. This article does not represent any party and, for the judgment and reference of the highest decision-making level in China, this article conducts an objective analysis on the possible war consequences along with their corresponding countermeasure options.”

Click here to read the entire analysis

Nuclear: one way around the energy crisis

An interesting chart on which countries use nuclear power. Seventy percent of France’s electricity is nuclear. Belgium appears to be similar. Germany has six nuclear reactors and would be better off it had more. It was going to close them; because of the war it has changed its mind.

The Gay Hussar is now the Noble Rot

I was in London this past week and had lunch in Soho twice, once at a place with my friend Iain Laird, who I have known since 1967.

The Gay Hussar acquired its name long before the word Gay took on its modern meaning. Not that it would have bothered some of its more famous patrons, many of them member of Parliament from the Labour Party.

Known as the Labour Party canteen, there were calls to save it as a “an important national institution”. Sentiment lost out. It closed in 2018 and the Noble Rot opened in 2020. Though far from a foodie, I have to report that the food at the Noble Rot, was excellent. I was embarrassed that Iain insisted on picking up the tab.

Essay of the Week

This week Harry Steele’s widow died. Catherine’s story is as fascinating as his and the two of their lives were intertwined in every way. This is chapter on Catherine from my book on Harry Steele.

Catherine Thornhill Steele

"There's a lot about business, my son, that's not very nice." Words of wisdom from Catherine Steele to her boys.

Catherine Steele is as responsible for Harry's success as he is. First, the two of them share a lifelong love affair; each supports the other unconditionally. Catherine is frugal, ambitious in her own way, and loves business. Her early forays into real estate, along with Harry's success in the stock market, paved the way for their joint business success.

Though she was raising her three boys, Peter, John, and Rob, Catherine came up with the idea of buying distressed residential properties in Dartmouth.

"I was looking for houses that were in bankruptcy so I could buy them, fix them up and hopefully make some money," says Catherine. "I studied music at the university, but I found that I had an affinity for business and I enjoyed it."

She did over three houses in Dartmouth that were in foreclosure. When Harry was posted to Gander, she started to look for similar opportunities. But Gander was a much smaller place, with a lot of government-owned housing connected to the airbase. There was not a large pool of housing to choose from, never mind trying to find a property in foreclosure.

The bank Catherine dealt with did have one interesting property, but it was a hotel, not a house. The Albatross, a rather apt name given the disastrous financial health it was in.

Catherine Steele transformed the Albatross from forty-eight rooms, one cook and two waitresses into a hotel with one hundred and thirteen rooms, five cooks and twelve waitresses. The success of the Albatross Hotel was the foundation of Harry Steele's business career. He could not have done it without his wife.

"My mother and father were a team, I know that's a cliché with a lot of people, but with them, it's very true. Besides being husband and wife, from the business point of view, they had very complimentary but different skill sets. They put those to work as a team to make the Albatross successful," says Peter Steele.

Catherine started in real estate while she was a Navy wife living in Dartmouth.

"When I was in Dartmouth I had bought a few houses that were in bankruptcy, and I fixed them up and sold them, so I went to the bank to see if there were any such things here in Gander. They said no, but we do have a hotel here that's in bankruptcy and would I be interested. That's how it all started. So I went to the bank, and they lent us the money. I don't think it had been run very well at all," says Catherine, too polite to be overly critical of the former owners even five decades on. She set about to teach herself how to run a hotel and went about it in a logical way.

"The Albatross wasn't a fascinating place, but as soon as I got it I went to the library in Gander, and I found a book entitled ‘Every Customer is my Guest.' I read that, and I met with the staff, and I would discuss things with them and what they felt would make their jobs a lot better. I will never forget one of the girls said to me, "Mrs. Steele, could we possibly have a pocket in our uniform to keep our tips in"? I hadn't thought of that, but I remember that to this day."

Every Customer is my Guest is 112-page book put out by the Department of Tourism of Nova Scotia in 1964 and reprinted several times. Its object is to help the owners of small hotels and restaurants. The book gives advice on the food side of the business, pointing out that waste costs money. It covers sanitation, dress, Every Customer is My Guest may have been written 65 years ago, but its advice is quite modern.

It talks about self-respect, both for the employee and the employer, and advises on how to handle difficult customers. Example: "The overfamiliar guest: Be courteous, dignified and ladylike. Avoid long conversations. Stay away from the table except when actual service is needed. Never try to give a `wisecrack' answer to a `smart' remark. You will only cheapen yourself and lower yourself to the rudeness of the guest."

Added to the book's advice was Catherine's common sense.

"I knew how I would like to be treated and I felt that I wanted people to feel as if they had come to my house. They don't leave saying "well I've been there twice, the first and the last time" that they would enjoy their visit and want to come back. That was precisely the way I wanted people to feel about this business. Once this lady came to me and said that the waitress had asked us if we enjoyed our meal and that has stuck with me to this day.

Under Catherine Steele's management, the Albatross Hotel was an immediate success. While Catherine ran the hotel, Harry would drum up business by speaking to airline crews landing at Gander.

"Mum ran the hotel organizing the menus and all that stuff while dad was busy in the Navy but trying to drum up some business for the hotel," says Rob Steele sitting in the dining room at the Albatross. "Eastern Provincial Airways was based here in Gander at the time, and the Crosby family owned it, and the flight crews would all stay at a competing hotel. So, my father called on the airline to try to get them to re-direct that business to his hotel. That's how he struck up an acquaintance with Keith Miller, who was then president of EPA."

That was the foundation of the success of the hotel, which the family owns to this day.

International flights also helped, as word spread about the Albatross being a decent place to stay. Gander was a refuelling stop on the way to Europe; planes going to Cuba couldn't fly over US airspace, so they too had to stop, coming and going.

At one stage rooms at the Albatross were in such demand that the same room could be meticulously cleaned and rented out again on the same day after flight crews had taken a short kip before resuming their journey, whether it was east, west or south. All flightpaths led to Gander. The Steeles acquired another hotel, the Sinbad. Catherine explains that the two are quite different.

"If it's a special event you would go to Sinbad's whereas the Albatross is more for travellers. But it was all new to me. My dad was a fisherman, so business wasn't on my radar at all," says Catherine. Both hotels benefited from being in the same town as one of the busiest airports in the world. Being in Gander, the airport was the vital part of the town, and we got just about all of them. We had all the pilots and flight crews staying at the hotel."

Janet Catherine Thornhill was born in Grand Bank Newfoundland into a prominent local family. The village of Grand Bank is on the southern tip of the Burin Peninsula. It is one of the warmest spots in all of Newfoundland, and its harbour is ice-free year round, one of the reason it was the centre of the fishery.

It is a small place with a lot of history. Grand Bank is only 48 kilometres from St. Pierre, with its sister island of Miquelon the sole territory of France left in North America. Catherine's hometown was once known as Grand Banc, owned by France. It was ceded to England after a European war that France lost, and then the Treaty of Paris in 1763, the result of General Wolfe's victory at Quebec, ceded St. Pierre and Miquelon back to France. The English inhabitants of those islands moved to Grand Bank, spelt with an English K, not a French C.

Catherine came from an accomplished family. Her mother, Ruth Williams, was a school teacher, an educated woman with a university degree from a college in the American state of Kentucky. Her father was a sea captain, a profession held in great awe and respect in Newfoundland. Catherine Thornhill came from a solid middle-class family, far from the subsistence living of Musgrave Harbour. But she still felt her father lived a precarious existence, even if he was successful and held in high esteem.

Catherine's father, Captain Arch Thornhill, was a legendary deep sea fishing captain. He started around 1918, fishing offshore in a dory, often with his brother or his cousin. Arch Thornhill recalls in the early 1920s he made $300 one year. But he was determined to succeed.

"I never gave up once in my life," he said. He said that as a young man he fished in a dory for seventy-two hours straight without sleep. That determination passed down to his children: Catherine who was pivotal in Harry Steele's success, and her brother Roland Thornhill, a successful stockbroker and a man who was once deputy premier of the province of Nova Scotia.

The rich fishing grounds call the Grand Banks are off the southern coast of Newfoundland, where the frigid Labrador Current, travelling down the coast of Labrador from the Arctic, meets the warm waters of the GulfStream. Cold meeting warm means the sea is often shrouded in fog.

Arch Thornhill's first command as a skipper was a schooner owned out of Nova Scotia. He borrowed $100 from a friend to buy two shares in the Vera P. Thornhill (no relation). It was February of 1927, and he was 27 years old. His first trip he commanded 24 men in the 170 ton, eleven dory vessel. The dories would leave the mother ship, go out and fish, and return to the main vessel.

The schooner was all sail, no engine, often at the mercy of the sea and the wind. On the first voyage, the wind pushed them into Gulf of St. Lawrence ice. It would be a while before the schooner he worked was fitted with an auxiliary engine.

The first trip was a success, and Captain Thornhill returned with 500-600 quintals of fish. A quintal equals 112 pounds (51 kilograms) of dried, salted fish. So that trip brought in about 67,000 pounds (30,000 kilograms) of fish.

There were even bigger catches, but the luck ran out, the majority owners of the vessel balked and Captain Thornhill, one of the youngest skippers in Newfoundland, had to wait for his next ship. Eventually, he went on to other schooners, including the Ronald George, which sailed in dangerous waters during the war.

Eventually, he went on to big trawlers, including the Blue Foam and the Blue Spray. On his 38 trips on the Blue Foam, he landed almost 6-million pounds of haddock, cod and other fish; just 28 trips on the Blue Spray landed 5.4-million pounds.

"Arch Thornhill was a very quiet and very modest individual. A very intelligent guy" says Raoul Andersen, the professor from Memorial University who wrote a biography of Arch Thornhill, Voyage to the Grand Banks: The Saga of Captain Arch Thornhill. "He was not a big man, but he was not a man who was afraid to tell people that he had employed as members of the crew to meet their obligation to meet their obligation to work. He didn't hesitate to tell a man that he had to get his rear end in gear or that kind of thing."

Later in life, Arch became close with Peter Steele, his eldest grandson on the Steele side.

"My grandfather Thornhill was my mentor. He and I were particularly close, and he was an interesting man. The context of Newfoundland society at the time was five or six families in St. John's controlled the economy under the banner of the Water Street merchants," says Peter.

"One of the assets or the pillars of the Newfoundland economy that they controlled was obviously the fishing industry as well as the import of whatever and the export of fish. People needed staples and consumer goods and so on. My grandfather was one of a very small group of people in Newfoundland society that would be, say, a very minimal size in numbers middle-class. He wasn't in the Water Street Merchants, but he worked himself up from rowing in the dory to being the captain of first, ships under sail, large commercial vessels and then on as a captain when they became motorized. I knew both my grandparents very well."

"My grandmother's name was Ruth Williams. The Williams' are a very storied and accomplished family in Newfoundland. My grandmother was a teacher in one of those one and two-room schoolhouses in a different part of Newfoundland than Musgrave Harbour, up around the Pool's Cove area where the Williams' were from. She obtained her education degree from, of all places, a university in Kentucky."

Almost all Arch Thornhill's fishing was on the Grand Banks. The weather could violent, and he knew many men who met their death at sea. He remembered a giant wave washing everything off the deck of a schooner, though no one perished, with one man diving down a hatch to save himself.On another occasion, the cannon misfired when he was setting it off to tell the dories to come back to the mothership. It blinded him temporarily, but he recovered.

It wasn't all fishing. There was a voyage to Barbados, to bring cargo and pick up rum. The major problem there was he was not experienced in sailing in warm waters. Not a major concern. Many seafaring men split their time between working cargo and fishing. When they would sail their schooners far afield: "..many `went foreign' as work required.", wrote Raoul Andersen.

Arch Thornhill's trip to Barbados was in the winter of 1931. He had never sailed on a foreign voyage, but he learned in a hurry before he left. "My wife had five brothers and four of them were foreign going captains." Two of his brothers-in-law gave him a quick course in navigating outside the coastal waters of Newfoundland.

He made it down to Barbados and back with a cargo of lumber on the way down and molasses on the voyage home. The owner of the schooner paid him an extra five dollars for a job well done.

One particular episode left his family worried. There were no radios on the schooner, and no one knew where they were.

"They were not sailing far, the vessel being moved from Grand Bank all the way over to the eastern part and haul it ashore and repaired and repainted. The terror of it was that it was almost six or seven days (that) the crew of six sailed and encountered all kinds of fierce weather," says the author Raoul Andersen who spoke to Captain Thornhill about the ordeal. "They had their sails blown out and a whole range of things that put a lot of pressure on them."

"I swore I would never marry anyone who went to sea because my dad went to sea and I saw how my mum worried." She remembered a time when her father was gone for those seven days, and no one knew if he was alive or dead. He was sailing from the Grand Banks to Burin on the south coast of Newfoundland."

A big storm came up, and he had to put the vessel out to sea and in those days on those ships they had no communication whatsoever. My mother had four children. I was the oldest, and I knew she was trying to keep up her spirits but I knew how worried she was and I promised myself then that I would never… and you should never say ‘never'… I would never marry anybody who went to sea. And look at this," said Catherine in a joking way, an obvious reference to Harry's years in the navy. "But I thought when I first met him that maybe I would meet somebody else through him. But he's very convincing and look at me here sixty-three years later."

Catherine was 24 when they married on Harry's 25th birthday.

Captain Thornhill retired from fishing in 1962 and died in 1977, one of the last schooner captains of the Grand Banks.

Catherine studied music at Mount Alison University, quite an achievement for a girl from Grand Bank, if only because getting there in the 1940s was not easy. Grand Bank, not to be confused with the fishing grounds known as the Grand Banks, is a town on the southern tip of the Burin Peninsula. Catherine explains the route she took, first heading north to get to the destination far south of her hometown.

"When I went to Mount A I was living in Grand Bank, so I got a taxi to take me to the center of the island, and from there I got the train to Port-aux-Basques where I got the boat over to Sydney. In Sydney I got a train to take me to Mount Allison. That was how I got to university. I don't remember now, but days, it seemed endless. Travel was terrible, but it was worth it."

That might seem an exaggeration to the modern ear, but the train that crossed the Island of Newfoundland was slow. The train on its narrow gauge tracks took 23 hours to travel from St. John's to Port-aux-Basques and the ferry terminal there.The ferry to Sydney was another 14 hours, and then there was a train to Mount Alison. It took determination to get there.

Catherine met Harry when she came back from Newfoundland with her music degree and started to teach. The couple met at a church dance, a chaperoned affair designed to allow young people to get to know each other.

"I started dating him when he was going to Memorial University, and I was teaching at Prince of Wales," recalls Catherine. She remembers she loved teaching even though not all of her students were born to music.

"Some parents wanted their children to take music, and they didn't have a musical bone in their body, but you did your best with what you had. I loved teaching, and I loved the children, and in the summer I would drive around town to see if any of them were outside playing or anything so that I could have a chat with them."

Catherine left teaching soon after their marriage because Harry was transferred to England. She loved living there. Because of the hotel business, she was more than a navy wife. Then at the age of 45, he gave up the navy and went into business full time.

"I was very happy about that because I loved business. I like people. I loved the hotel business and working with the staff because I was learning as they were learning."

Their firstborn son Peter is blessed with a formidable memory, and he knows the family history, including things that happened before he was born, such as his parent's courtship.

"My father was in St. John's studying education at Memorial, and my mother was living in St. John's and they met there," says Peter. "Back then a lot of people met and entered into courtship or were introduced to each other before courtship, through church-sponsored dances and activities that were chaperoned and supervised. They met through the United Church sponsored activity and from that introduction things evolved until they got married."

People who got to know Harry Steele later in his business came to admire Catherine as much as they did Harry.

"She's a terrific lady, very kind. Her father was the last of the captains of the schooners," says David Bruce, who was born in Scotland and was one of Harry's prime stock brokers in Toronto. "They had a hard upbringing as they all did on Newfoundland. She wouldn't see her father for months at a time when he went over to the Grand Banks. She knew the day he was leaving because he used to leave a silver coin underneath her egg cup. She always looked underneath the egg cup for the coin, and she'd know he was leaving for a voyage. She is very musically minded, and her father bought her a piano when she was eight or nine years old. They brought it onto the deck of the schooner, and they lifted it off the boat up to the house, and she has been playing the piano ever since."

Seymour Schulich, the mining entrepreneur and philanthropist, donated a chair of music in Catherine's honour at McGill University.

Rex Murphy, perhaps the most famous son of Newfoundland because of his broadcasting on the CBC and his opinion columns in the National Post, remembers the Albatross and how hard Catherine worked to make it a success. Rex would visit the hotel when he was filing items for CBC television.

"I remember we would go on our shoots and it was a thing we'd go to the Albatross because the food was so good. And that was all the small kitchen and Mrs. Steele making sure that they put out good grub. I stress this that it's very true that (out of) the family and Schulich and Craig Dobbin, Catherine is the key. That union is a union, and even with all his bluster, Catherine still has equal standing. He's a great patriarch, but in fact, there are two people fused into one. You're not taking on just him; you're taking on both of them."