Milan, Easter, London, the Ottomans vs the Romans and an Italian family in Sudbury.

April 21, 1965 Volume 6 # 3

Milan: the Business Capital of Italy

The Galleria in the center of Milan. Though Rome proper has more people, the Metropolitan area of Milan, 7.5-million, is by far the largest in Italy and one of the biggest in the European Union. It is more than fashion and opera. Milan is a financial center and it is said to be attracting new business, the likes of hedge funds and private equity as some people are shunning the Trumpocracy or running from Labour’s tax attack in London that has already started an exodus of the mobile rich.

Italian Men: the World’s Best Dressed

Milan Design Week April 2025

It was earlier than our visit but here are some shots from Shutterstock.

Plates

Lamps

The Duomo, Milan’s Biggest Tourist Attraction

Don’t be fooled by the empty church. The lineup this week, outside in the rain, was an hour, and that was with pre-booked tickets. Construction started on the church in 1346 and it is still being modified. St. Peter’s in Rome is larger, but because the Vatican is a separate country, the Milan Duomo is the largest in Italy.

Mea Culpa

Last week I said Genoa is the largest port in Italy. A friend pointed out it’s Trieste.

Hung Out to Dry

The Innards of Air Canada’s New Airbus A321XLR

“Air Canada’s first Airbus A321XLR is now under construction at the manufacturer's Hamburg Finkenwerder site in Germany,” writes the website, Simply Flying. “The aircraft is the first of 30 of the type the Canadian flag carrier hopes to take delivery of over the next three years.”

Right now all they have put in is the electrical wiring and air conditioning pipes. All the stuff you don’t see when you’re flying. This is just the rear section of the plane.

Underneath is the rear fuel tank, new in this A321XLR. It holds 13,000 litres of fuel. That helps double its range to 8,700 kilometres or 5,400 miles, allowing it to fly across the Atlantic. Air Canada has the 11th largest fleet of aircraft in the world.

This stretched version burns 30% less fuel and carries about 184 passengers, the same as the older model A321. It earns 12% more per seat for the airline.

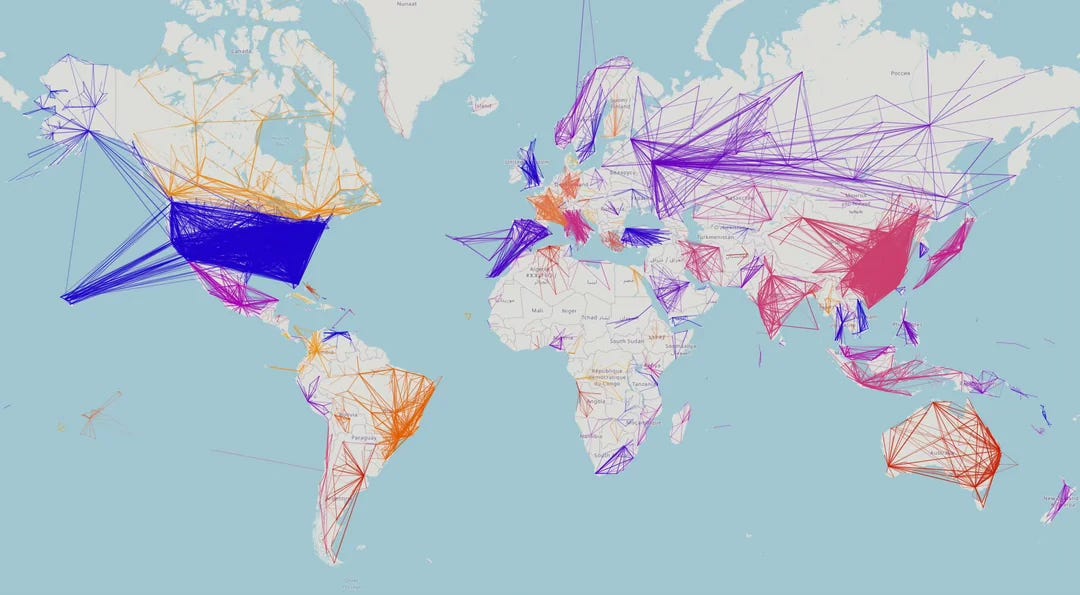

Domestic Flights in Each Country

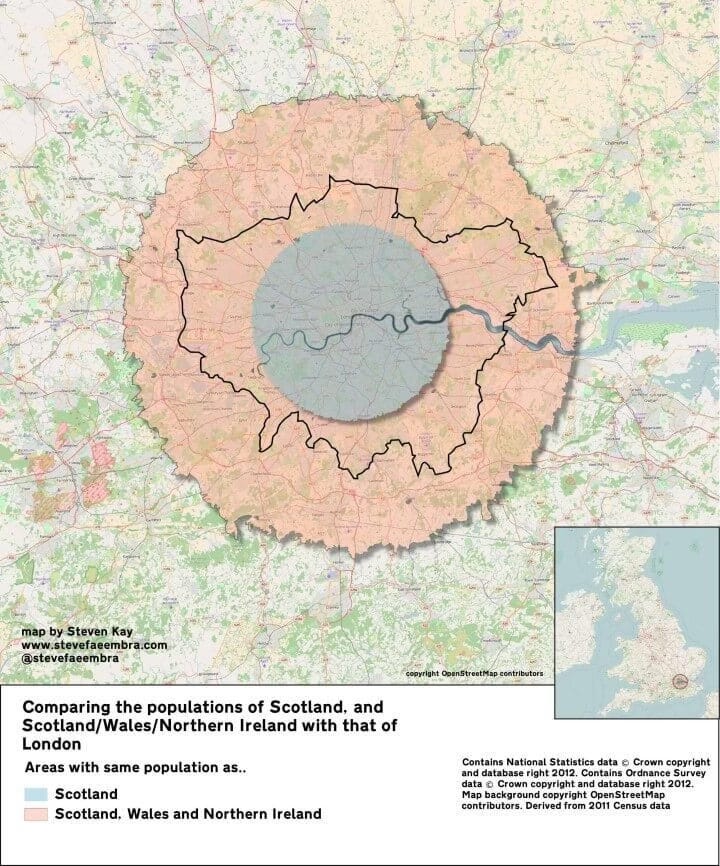

London versus the Celtic Rim

Well the Welsh aren’t Celts, but you get the drift. The grey part is the population of Scotland, Greater London is contained in the black line and the brown ring includes Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

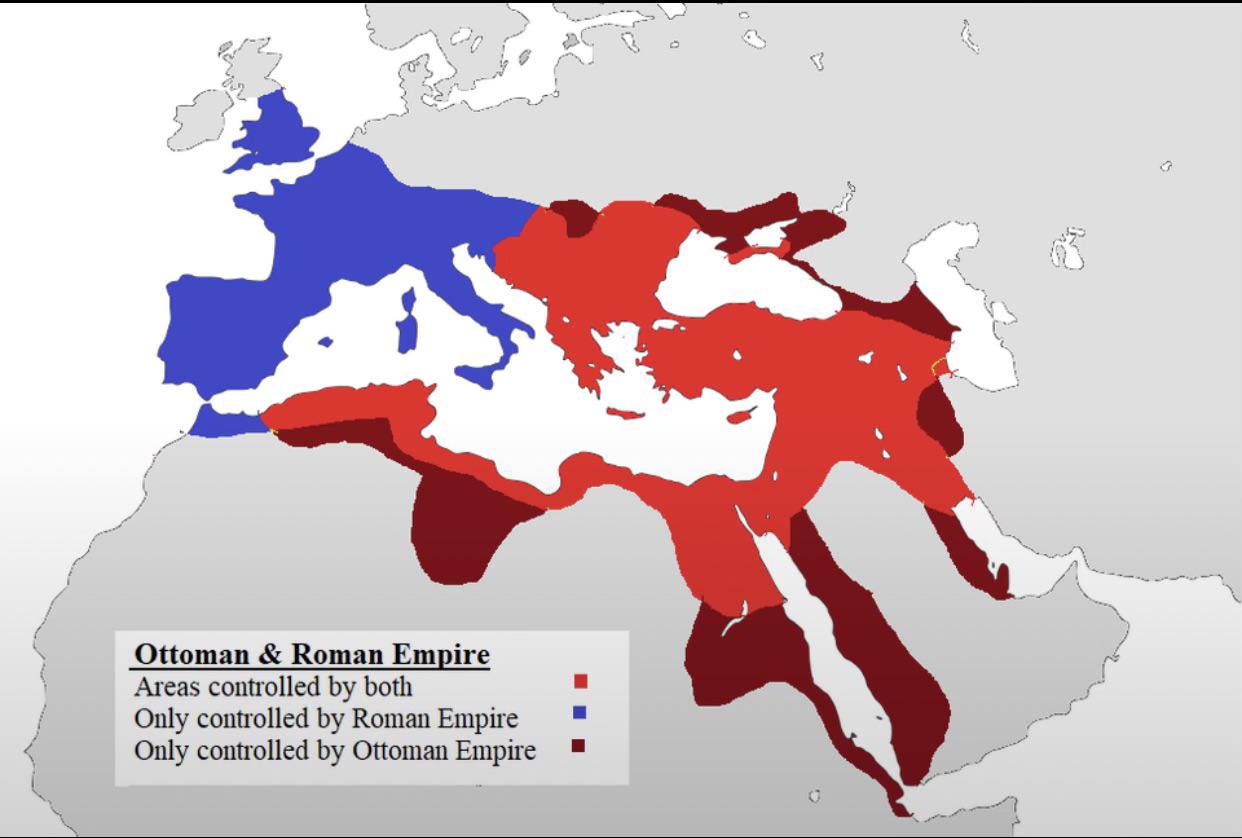

Rome vs the Ottoman Empire

This was at the peak of each, 117 AD for Rome, 1600s for the Ottoman Empire. Rome lasted much longer, If you count the Roman Republic and the Byzantine Empire, conquered by the Ottomans in 1453.

Buona Pasqua

Basilica Santa Maria Assunta, an amazing church for Camogli, once a small fishing village. This was taken in the week before Palm Sunday. I was there and the church was packed. Italy may have its secular side but it is still a very Catholic country.

Passion Ballet

A modern ballet in the opera house in the same small town. The dancers were spectacular but it was hard to figure out where it was all going.

The final scene left nothing to the imagination, performed on the day before Good Friday.

.

Essay of the Week

I have written books for three Italian Canadian families: Aldrovandi, Ciccolini and Dellelce. This week I am using chapters 2 and 3 from the Dellelce book. The family is from Sudbury in Canada and Abuzzi in Italy, near a village called Elce.

Chapter 2

The road through Elce in Abruzzi. All photos by me.

Fare Fortuna

Fare Fortuna. A two-word Italian phrase meaning to make a fortune: it was the reason almost every Italian crossed the Atlantic Ocean to Canada, the United States, or Argentina. They were leaving behind a world of poverty and near feudalism to come to a place where they could work hard, save to own property, and build a better life for themselves and their children—something it was almost impossible to do in Italy 100 years ago.

The extended family that makes up the Dellelce clan is an example of Fare Fortuna. The work ethic and entrepreneurial spirit now spreads into the fifth generation, the great grandchildren of the poor Italians who made their way to Sudbury just before, and during the First World War.

Italians are the second largest group in Sudbury, after Canadians of English and French descent, and they are among the most successful people in the area.

The Dellelce and Scagnetti families arrived in the first wave of Italian immigration. There were some Italians working in the area in the late 1800s, but the first big wave came in the years before the First World War. One might ask, how did a poor Italian living in a remote part of Italy, who may not even have known what was going on in the next village, discover there was work 7,000 kilometres away?

Diane Dellelce’s father, Beniamino (Ben) Scagnetti, arrived in Canada from northern Italy in May 1913. He sailed on a rather small passenger ship, the Verona, leaving from Genoa, and stopping in Naples to pick up other passengers before sailing to their final destination in the New World: New York City. From there, he made his way to Buffalo, New York, and then on to Sudbury. At the time, it was common for immigrants from Italy to enter Canada through New York City.

There were three waves of Italian immigrants to Canada in the 20th century, and the Scagnettis and the Dellelces were part of the first group to come here. Being one of the first Italian immigrants to Sudbury gave Ben Scagnetti an advantage, as he started his fledgling businesses and waited for his future wife, Cristina, to arrive.

Cristina Della Vedova was from the same region in northern Italy as her husband. She sailed from Genoa to New York aboard the Duca Degli Abruzzi, a coincidence in that her daughter, Diane, would marry into the Dellelce family, who were from Abruzzi. She arrived in New York City on October 4, 1915, one of the 1,740 third class passengers on the ship. Records from the time described her as having blue eyes and black hair.

Italy had joined the Allied side in June of 1915, and there was some danger in the Atlantic from German U-boats (submarines), and the Milazzo, a ship owned by the same shipping company as the Duca Degli Abruzzi, was sunk by a U-boat in 1917.

Thomas Dellelce, born Tommaso Dell’Elce, sailed from Naples to Halifax, Nova Scotia, one of the thousand or so passengers on the Palermo, arriving in Halifax, Nova Scotia on July 25, 1913. In December of 1916, a German U-boat off the coast of Spain sank the Palermo. Immigration papers record that Tommaso was five feet eight inches tall with dark complexion, dark brown hair, and brown eyes. Not every ship manifest and immigration record went into such detail.

Tommaso’s future wife, Rachelina Masciangelo, later known as Lina, was only three when she arrived from Naples aboard the America, docking in New York City on March 9, 1916. There were a number of different ships of that name at the time, including one built by the same company that built the Titanic. However, Rachelina travelled on an Italian vessel of that name, used mainly for the transatlantic run to New York.

Rachelina arrived with her 67-year-old grandfather, Pasquale, a shoemaker, and her mother, Ginevra, who was 25 at the time, and on her way to meet her husband, Enrico, who had arrived in Halifax a few years earlier. It was common for single Italian men to arrive on their own, and then when they had made enough money, send for their wives or fiancés. Some even returned to Italy, and Tommaso Dell’Elce was an example of that, as he criss-crossed the Atlantic three or four times.

Word of the booming mining towns in Northern Ontario reached the villages and towns of Italy in the years before and during the First World War. At the time, immigrants made up just a small part of the local population of Sudbury and the Finns and Ukrainians outnumbered the Italians.

The British Canadians who made up the bulk of the population were, in many cases, xenophobic and anti-foreigner, and Italians were Catholics, anathema to the Protestant members of the Masonic Order who dominated management at Inco. This prejudice was strong, even during the First World War when Italy was on the British side. The Scagnettis spoke only English to their children at home; the Dell’Elce family changed the pronunciation of their name to a more Anglo sounding Dell-eece, though the spelling remained Dellelce. This was not the tolerant age of multi-culturalism. There was no tolerance for ‘foreign’ languages.

Inco was desperate for workers in the early 20th century, and it couldn’t get enough from the rest of Canada or Britain. The company used labour agents in Italy to find people who wanted to move to Canada. The labour agent would go to a town or village and post notices in the town square or other prominent public places. The agents would then arrange the voyage, from Genoa for people in the north, like the Scagnettis, or Naples in the south for the Dellelces and Masciangelos.

Some of the labour agents lied to the potential immigrants about what they could expect. The Canadian Encyclopedia reports a newspaper in Milan reported on the scandal of Italian peasants becoming indentured labour in northern work camps. In 1904, there was a Royal Commission in Canada to investigate these charges and they were cleaned up before the Dellelce, Scagnetti or Masciangelo families left Italy.

This form of immigration, with labour agents working specific geographic areas, meant there were larger groups of people from the same village who emigrated en masse. For example, 5,000 immigrants from the Italian region of Marche moved to Copper Cliff to work in the mine and smelter there. Marche is just north of Abruzzi, home to both the Dellelce and Masciangelo (Rachelina Dellelce’s maiden name) families. There were, in fact, few families from Abruzzi in the Sudbury area.

It was easy for people from the same region to live together. Many of them would know each other, and they spoke the same dialect. Italy has 20 different regions and as many as 1,600 separate dialects, as villages isolated from each other for centuries developed a different way of speaking. It was certainly true of the Dellelce and Scagnetti families who came from regions 600 kilometres apart. Theresa Dellelce commented that her mother and father’s dialect were very different. Diana Iuele-Colilli, a professor of Italian at Laurentian University in Sudbury, says the Scagnetti dialect from northern Italy near the border with Slovenia would be incomprehensible to a person from Abruzzi.

“They wouldn’t have understood each other at all,” says Ms. Iuele-Colilli. “Friulan (the language of the Udine region) is a separate language.”

Ron Scagnetti said his mother used to make Italian pastry with a neighbour across the street in Garson. The woman was from Calabria, the region in southern Italy that sent the largest number of Italian immigrants to the Sudbury region. He recalled that when the two of them spoke Italian, Cristina Scagnetti found her Calabrian neighbour almost impossible to understand. The Scagnetti family first lived in Creighton Mine, which was shut down by the mine owners, and turned into a ghost town; they moved on to Garson, another town built around a mine.

Many Italians worked for mines, either above ground or below, but working underground was more dangerous and because of that the hours were shorter and the pay was higher. Tom Dellelce was the only member of the Dellelce or Scagnetti families to work directly for the mines; he was a locomotive engineer for Inco. But, he branched out later working for Inco, and running a business with his wife on the side. Starting small, both families created much more wealth as entrepreneurs than they ever would as employees.

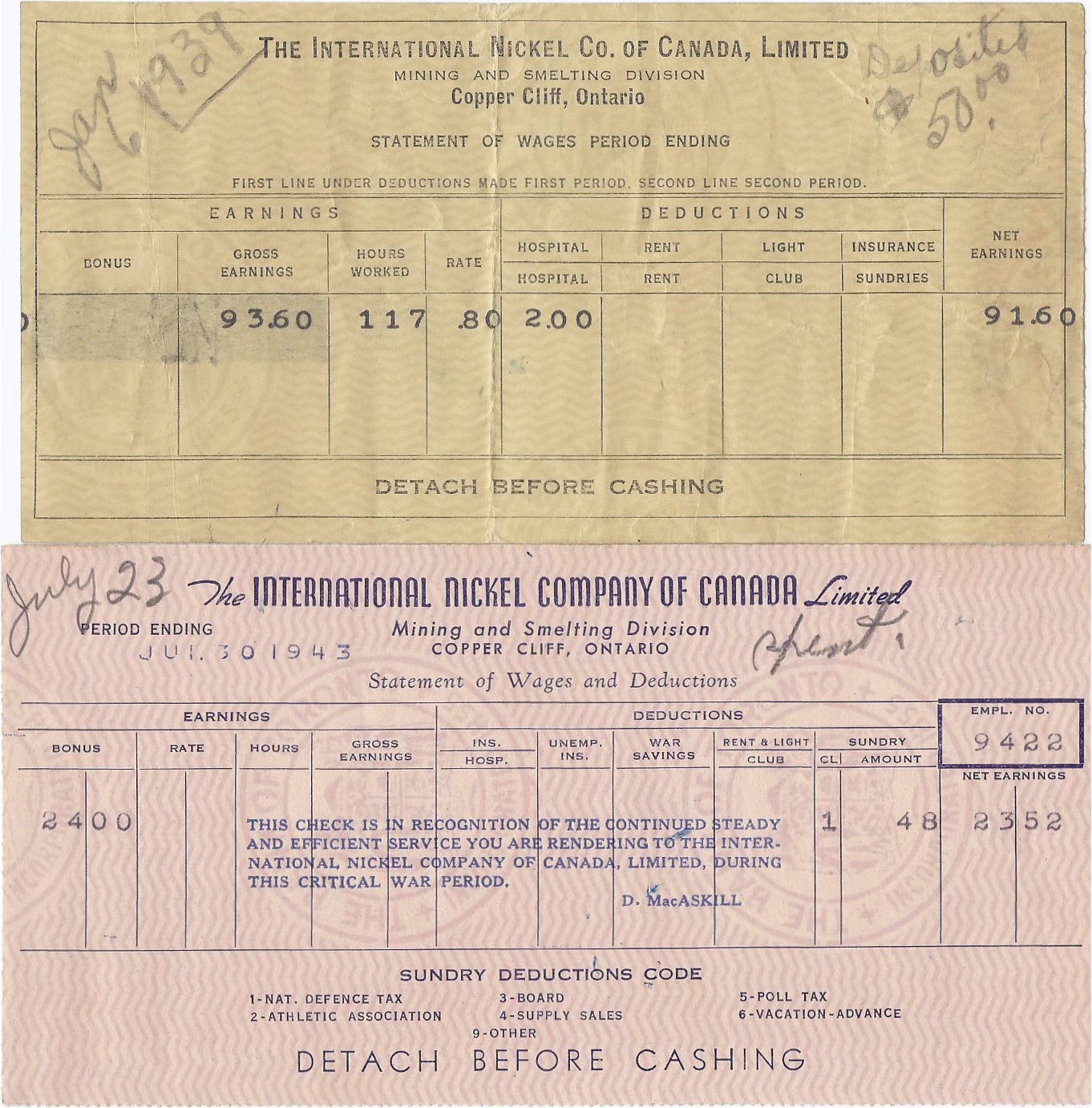

Tom Dellelce’s paycheques from Inco

The January 1939 cheque is for two weeks’ work (117 hours) at .80 cents an hour. The July 1943 cheque is a $24 bonus for the period of the Second World War. By then, his pay was .90 cents an hour.

Many of the people who left Italy planned to return, promising those at home that they would be back in five years, after they had made their fortune. The posters in the town square promised riches, immense sums compared to what a poor Italian could make at home. Reality was often something else. The weather was harsher, the work was harder than expected, and the wages not what they dreamed. Some Italian immigrants found Canada too tough and went to the United States; others went home, disillusioned with life in the New World.

Though most stayed, there were those who managed a kind of trans-Atlantic shuttle, including Tom Dellelce who returned to Italy at least three times prior to his marriage to Rachelina, according to immigration records. Once he married Rachelina, he stayed put in Sudbury

Other Italians worked in the mines in Sudbury in the summer, and then would take the train to other places for the winter. Trail, British Columbia, was a favourite spot since it too was a frontier-mining town. Italians were relatively frugal; there weren’t many heavy drinkers, as they were used to wine and could handle it. The idea was to save money, not spend it.

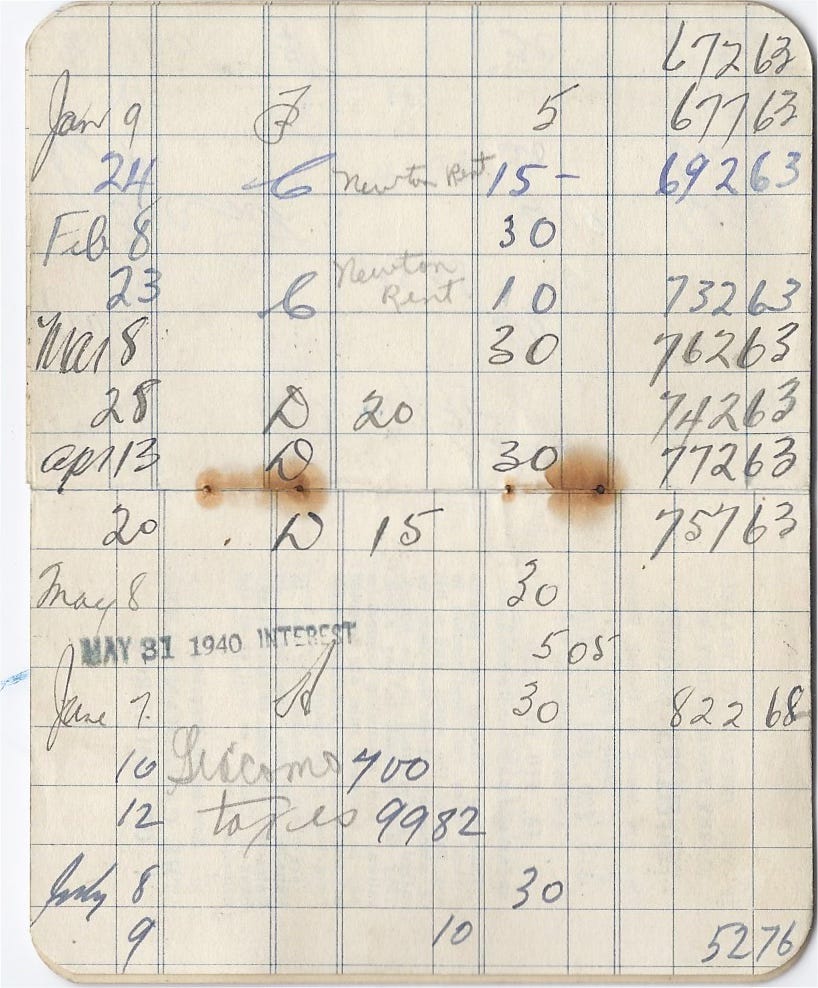

Tom and Lina Dellelce’s savings book from January to July 1940

As the illustration above shows, the Dellelce family were diligent savers. The amounts may not look like much, but that $700 withdrawal would be worth about $12,000 today, according to the Bank of Canada’s inflation calculator. In 1940, you could buy a brand new Ford V8 sedan for $732.

When Italians made money, it didn’t stay in the savings account for long. They invested in real estate. Ninety per cent of Italian Canadians today own their own homes, compared to a national average of sixty-nine per cent. They also tend to want solid houses of brick construction, something that announces to the world that they have made it. Certainly the Dellelce and Scagnetti families made a lot of their money in property: boarding houses to hotels, building single family homes to turning large tracts of land into new neighbourhoods.

Professor Iuele-Colilli, who has written two books on Italians in Sudbury, says these immigrants almost all succeeded in one way or the other. “Italians are hard workers. They don’t get involved in things such as heavy drinking and especially not in Sudbury. The goal was to make money and nothing else. Their vices are cards or bocce, but that’s all.”

Italians came to Canada because of economic opportunity. Almost all of the Italians who left Italy were poor. Italy in the late 19th century was one of the poorest countries in Europe, especially in the south and northeast, and its social structure had a land-owning aristocracy at the top of it all who made it difficult to buy land. Farmers leased their holdings from large landowners. Starting a business in Italy 100 years ago would have been all but impossible for the likes of the Dell’Elces and Scagnettis. In Canada, they worked hard and prospered, and because of their Italian roots and the class system there, when they did make money, they invested in land and buildings, something solid and unheard of back home.

At the turn of the 20th century, there were only about 11,000 Italians in Canada. Three quarters of the immigrants came from poor southern regions, such as Sicily, Calabria, Molise and Abruzzi. Few immigrants came from the north of Italy, the exception being those from the Friuli-Venezia Giulia region, a largely rural area to the northeast of Venice, from where the Scagnettis came. Part of the reason for the dissatisfaction of rural Italians from the south was the dominance of the northern Italians, who controlled the political and business life after the final unification of Italy in 1871.

There was a huge surge in Italian immigration from 1900 until the First World War when 119,700 Italian immigrants entered Canada, according to the Canadian Encyclopaedia, the biggest year being 1913, when the patriarchs of the Dellelce and Scagnetti families arrived: young single males, who would later send for their brides to join them. The war slowed down immigration, though Rachelina Masciangelo and her mother arrived in 1916 as the war raged in Europe, and shipping tonnage was primarily devoted to moving troops and war materiel, not passengers.

There was little immigration in the 1920s, and economic opportunity in Canada dried up in the Great Depression of the 1930s. During the Second World War, many Italians were interned as so-called enemy aliens. This did not happen to any of the Dellelce, Scagnetti or Masciangelo clans, who were all loyal Canadian citizens by that time.

America was discovered by an Italian, Christopher Columbus, and named after an Italian, Amerigo Vespucci. The first Italian to land in what is now Canada, was Giovanni Caboto from Venice, but in the pay of the English King when, as John Cabot, he laid claim to Newfoundland for the British Crown. In spite of this early history, there were prejudices against Italian Canadians, even those who were citizens. The Dellelces, the Scagnettis, and many other Italian families ignored the limits placed on foreigners by the Protestant establishment by going around the system as self-employed entrepreneurs.

3

The Dellelce Family’s Early Years

Tommaso Dell’Elce, the handsome young immigrant ready to take on the New World

Tommaso Dell’Elce arrived in Canada on July 25 of 1913, with $20 in his pocket. Though that may not sound like much, it was worth almost $500 in today’s money. He was 18 years old. His future wife, Rachelina Masciangelo, arrived almost three years later at the age of three; her relatives were listed as having just $2 between them.

Tommaso was born on May 7, 1895 in a small village in Lanciano in Abruzzi, called Villa Elce. The family name means “from Elce” in Italian. Below is a bell tower in Elce across the road from the house where Tommaso was born.

In Italy, he had worked for the railway as a track boy, keeping the roadbed clean. When he arrived in Sudbury, not speaking any English, he found a job with the Canadian Pacific Railway as a water boy, then a labourer. Eventually, he moved to Inco, and its private railway and became a fireman, stoking coal into the boilers of the steam engines. He then graduated to railroad engineer, driving the steam locomotives for Inco. He had to work to qualify as a locomotive engineer, a prized job on the railway and one that paid well. There were many perks and it was a job that was at the top end of the working class.

Tommaso, or Tom, as he became known in Canada, led a more complex life than most immigrants, and travelled back and forth to Italy three times between 1913 and 1925, according to ship manifests, and immigration records. Not only did he live in Sudbury, but also in Montreal and Trois Rivières in Quebec, and possibly St. Catharines, Ontario. Only when he married Rachelina did his life follow a straight line.

Enrico Masciangelo came to Canada first, then sent for his wife, Ginevra Delazizza, and their daughter Rachelina, once he was established. On her immigration papers Ginevra listed the reason for coming to Canada as “to come to husband.” Both were from town of Fossacesia, in Abruzzi, which is on a hill overlooking the Adriatic two kilometres away. It is 11 kilometres away from Villa Elce in Abruzzi.

The Masciangelos first settled on a farm in Markstay, and Rachelina went to school there. Later, the family moved to Sudbury. Like all immigrant families, they worked hard; there was no social safety net, so it was sink or swim. Enrico’s occupation was listed as fireman in 1926, though that could have been on the railway, stoking steam engines, as Markstay is on the main CPR line. Eventually, Enrico opened the first boarding house in Sudbury, at 207 Kathleen Street. It provided room and board for as many as 50 miners and railroad men.

Rachelina finished primary school and then worked in her parent’s boarding house, later known as the International Hotel.

“When I was young, I told my dad that I wanted to go to school, and get higher education, but dad said `no, you work here (at the boarding house) and help your mother,’ ” Rachelina told the Sudbury Sun newspaper many years later. “And so I did. My mother taught me everything.”

Maybe because Rachelina grew up as a Canadian, she had an edge on her husband who arrived as an immigrant, because as her life would later show, she had street smarts.

By the time he was 36, Thomas Dellelce was not rich, but he earned a good wage as a train engineer. He lived at the Masciangelo’s boarding house, as many unattached males did at the time.

Theresa Olivier, Rachelina’s youngest daughter, recalls how Tom and Rachelina came to be married: “My grandfather ran the boarding house and had borrowed money from my dad, who was one of the boarders. Eventually, my grandfather could not repay him. He asked my dad what he would take instead, and he said “your daughter.” She was seventeen, and he was thirty-six.”

They married in 1929 and their first child, Nicholas, always known as Nick or Nicky, was born on July 19, 1931, followed by Tom Jr. on November 10, 1932.

Tom Jr. had the same personality as his easy-going father, who was someone that stayed in the background. Though his younger wife earned the reputation of being a clever entrepreneur, family members recall he, too, was a hard worker.

“He never got the credit he was due. I mean the (Sorrento) hotel, and all that, I know she was the head honcho but he worked hard too,” says Terry Dellelce, Tom Jr.’s widow. “He built many houses here in Sudbury. In fact, we just moved from the very first house he built up on Elm Street. Plus, he worked for Inco, he drove the trains. So he was no slouch, he worked hard.”