Oil Back to $100 a Barrel? Pricey Electric Cars and Runing Away to Sea

Ocrober 14, 2024 Volume 5 # 18

Is Oil on the Way Back to $100?

Oil was well above $100 a barrel just two years ago. It closed at $75 on Friday and Barron’s is musing that it could go back to $100. War in the Middle East is the reason. The dramatic image below is a Greek oil tanker on fire in the Red Sea after a rocket attack by Houthi rockets fired from Yemen.

An oil price of $90 or $100 would hurt drivers worldwide and hit poorer countries where rising prices produce more relative misery. Higher prices would help Russia and Iran become richer and make it easier for them to finance their wars. It also helps Canada where expanded pipelines to the Pacific mean more markets than just the USA. The farm fields of Alberta, shown below, are dotted with oil wells along with huge deposits in the oil sands in Alberta’s north.

Will People Start Leaving Florida?

The Wall Street Journal thinks so.

But a friend who has a business and a condo in Florida says this happens every time there is a storm. The reality of another northern winter sends people south. Real estate has been slow across North America and maybe Florida isn’t an exception. That said, two hurricanes in a row might have some people planning to move.

Miami was already in the Bubble Zone and it was untouched by recent storms.

Boeing’s Problems Mount

First it was two crashes of the Boeing 737 Max, pictured below., killing 346 people. Then a door fell off an Alaska Airlines 737 Max in flight.

Two Astronauts taken to the International Space Station on a Boeing spacecrft are stuck there, probably until next year. About 33,000 Boeing workers are on strike and this week Boeing announced it is cutting 17,000 jobs and dealying its 777X airliner.

The stock price just about cut in half.

Mercedes’ Top Electric Car

Sitting in the Mercedes dealership while my nine year old diesel Mercedes was being serviced, I saw this huge black car with EQS stamped near the driver’s mirror.

It is the top end electric sedan from Mercedes.

The Price Tag

So that $190,804 would be $215,608 with the sales tax. That is enough to buy a decent house in Moose Jaw. I checked.

The car looks gorgeous and Car and Driver decribes it as: “…opulent experience—but in a body so softly rounded, it looks like it has been melting in the summer sun.” They love the interior.

But the flattery stops a few paragraphs later. Car and Driver lists it at number 13 among luxury electric sedans. “Our chief complaints about the EQS are its blasé driving personality and its mushy, disconnected brake pedal feel. If you're prioritizing a plush, quiet ride the EQS delivers exactly that. That its rivals—a list that includes the BMW i7and the Lucid Air—offer both similar panache and better road manners makes the EQS a harder sell.”

The most expensive Lucid Air costs more than the EQS.

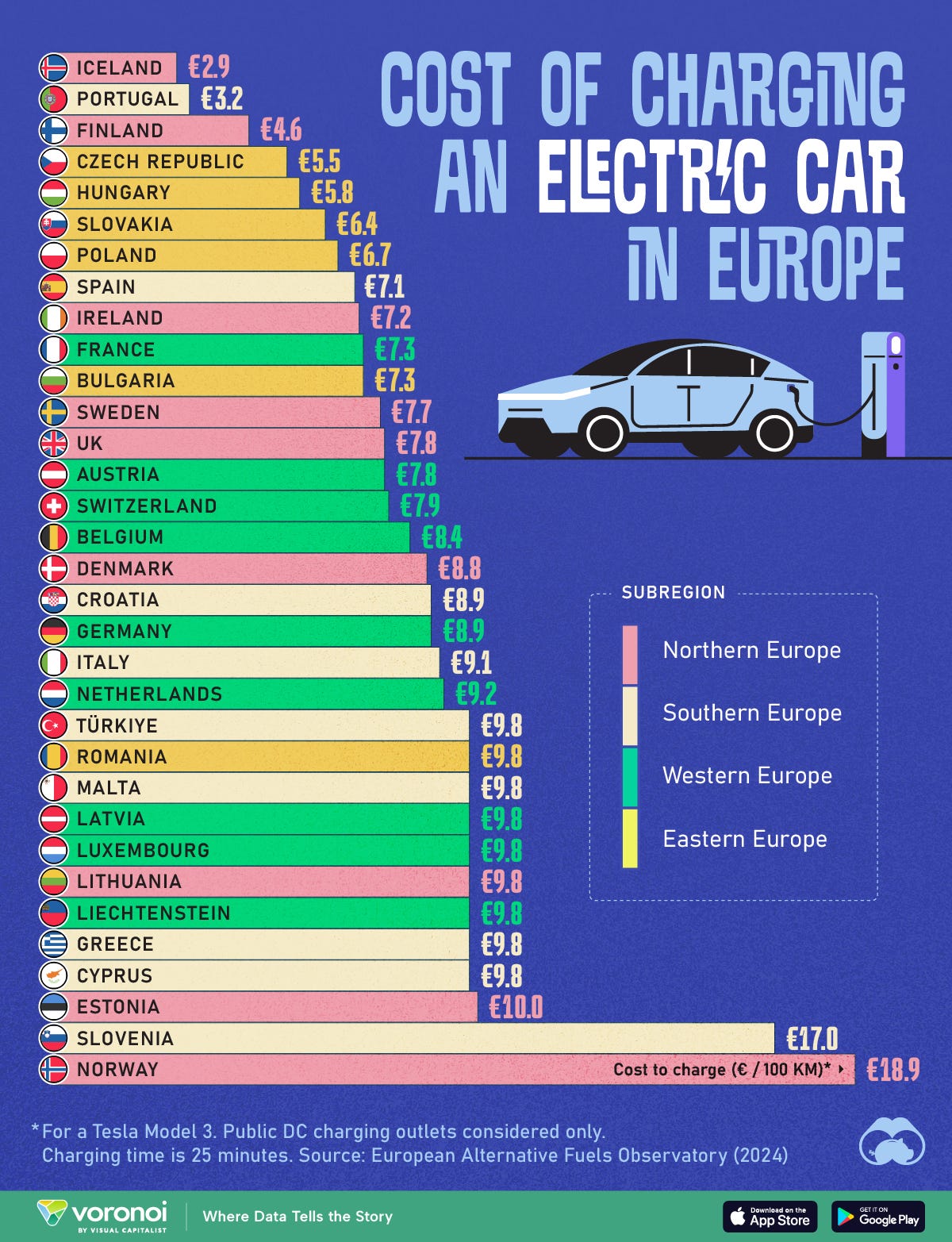

And Charging EVs in Europe

The prices at public chargers. Rich Norway, which subsidieses the pirchase of electric cars, soaks the drivers when they need more juice.

Essay of the Week

This is a chapter from the book I wrote on Bill Marshall, who was a Spitfire pilot during the war and then a horse trainer. Another find from a recovered hard drive.

Down to the Sea

Bill Marshall ran away from home when he was 14. Wearing just his schoolboy’s flannels and a jersey, he rode his bike from his home at Chichester in West Sussex to Portsmouth in Hampshire, the port where he signed on to see the world as an ordinary seaman, the lowest of the low.

It’s not far from Chichester to Portsmouth, only 15 miles in a straight line and about 17 by bicycle. But the two places might as well have been on different planets. Chichester, the pleasant town of 13,911 souls near the seaside where retired naval officers like Bill’s father lived and kept their small yachts; and Portsmouth, a city of a quarter of a million out of place in gentle Hampshire, the tough port where freighters picked up their orders and their crews.

Many boys in England left school at fourteen back then and were apprenticed to a trade or even signed up as seamen on ships. They weren’t old enough to vote but they were old enough to do a man’s work, though many who signed on to a freighter didn’t know the hard life they were starting. Still, it was a form of apprenticeship and the man who was the skipper of Bill’s ship started his life at sea as a boy seaman.

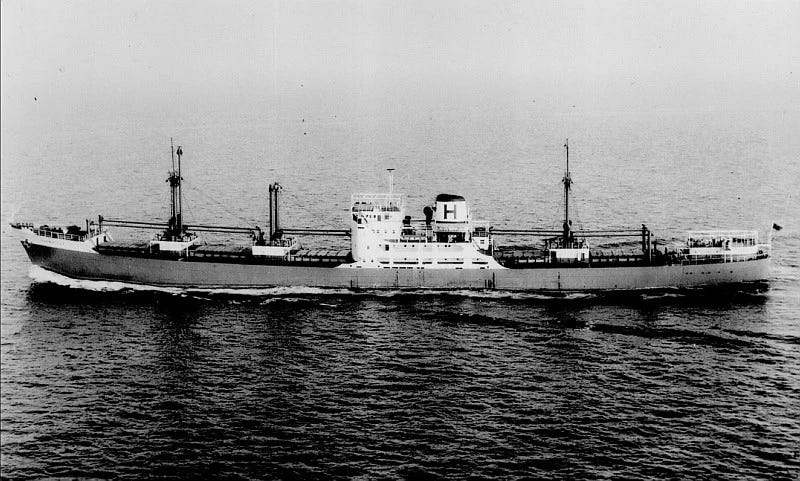

The ship Bill signed on to was the Harmattan, named for a dry, dusty wind that in the late autumn and early winter blows along the northwest coast of Africa, carrying cooled air east from the Sahara. When the Harmattan blows out to sea it can sometimes be as thick as a red fog, leaving the sands of the dessert on the deck of ships off the coast. It was a similar wind that would help carry Bill Marshall back to England almost seven years later. But he didn’t know that then, and this was the fall of 1932 when a skinny boy wanted adventure and not school.

Bill had run away from home because his father had him down for public school, in his case, Rugby, made famous in Tom Brown’s Schooldays and later in the racy books detailing the fictional adult life of Flashman, the school bully and arch cad.

It wasn’t that Bill had a rough childhood, just that he was a strong minded young man who rebelled against his father earlier than most.

Growing up on a farm just south of Chichester young Bill had been around horses almost all his life. His father bought him an unbroken New Forest pony. He had to break it himself and was thrown off time and again, but in the end he rode it.

“He bucked me off millions of times. Eventually the pony and I had an agreement. He didn’t buck me off and I didn’t keep chasing him,” remembered Bill. He also remembers the size and age of the horse. “He was only a yearling. We grew up together. I had to use a box to get on him. He was only ten or twelve hands.”

Bobby was what he called the pony, was the first horse he ever trained. From them on Bill was at the stables every day. He was a natural rider and used to work for a horse dealer, keeping his horses in shape by taking them out on hunts.

“I used to take a horse from Chichester, hack it to Horsham—that would be 25 miles—go to the meet and then be over by four in the afternoon. By the time I hacked home it was almost midnight.”

His parents were unsettled by his obsession, but then a young boy could be doing a lot worse than spending all his spare time with horses. There was one incident which unsettled them. Young Bill enjoyed hunting so much, he came up with a scheme to skip his day school north of Chichester, and ride instead.

“I. wrote the headmaster and told him I wasn’t going to be coming to school that term, because I’d broken my leg. Well instead of going to school I went hunting every day. Unfortunately my father ran into the headmaster after about two months. He said to my father `How’s the leg coming along?’ My father said `Leg, leg? You should know, he’s with you isn’t he?’ Well of course there was one hell of row. I should think I was about 12 then.”

Marshall has nothing but good memories of his father, Cyril, even if they did row when he was a boy. And he spent an idyllic childhood in rural England, which he remembers as a perfect place. He saw a lot of it from the back of a horse, high up, and a lot of it low down, near the hedgerows that make the English countryside such a beautiful patchwork place.

When he wasn’t at the stable, riding in the hunt or at school, young Bill spent a lot of time with the men who kept up the hedgerows in rural Hampshire. He liked to listen to their stories, which were lessons on the wildlife living in the thick bushes that separated one field form another, or the pasture from the road.

It was just a short time after his father caught him playing truant, that Bill met a farmer near Horsham. The man was interested in point-to-point racing and had what he though was a pretty good horse. But he was what Bill described as `Not a very fashionable fellow’ who couldn’t get any of the local amateur jockey to ride his horse.

Bill was his man. “And I was lucky enough to win. I rode four or five winners. And after that people wanted me to start to ride their horses.”

Point to points are also know as steeple chases, the races over green covered hurdles masquerading as hedgerows, the pinnacle of which was, and still is, the Grand National. That’s what Bill wanted, the life of a steeplechase jockey: horses, excitement and the feeling of kinship he felt with the other men and boys at the tracks. By the age of 12, his mind was made up. Horses were what he wanted to do with his life, and nothing could change his mind. In fact, nothing ever did.

An amateur rider was one thing, but the son of a naval officer becoming a jockey was preposterous. His father, grandfather and great-grandfather, who had been headmaster of Brighton Grammar School, had all gone to Rugby. Bill was good enough at school, but the thought of being lectured to by a master, and having to obey the petty rules and whims of older boys was enough to drive him from home.

Australia was where he wanted to go. A place where he could ride all year, and far away from the rules laid down by his mother and father. He was determined to go to sea and make his fortune. His first stroke of luck was selling his bicycle for 10 shillings before heading down to the docks to pick his ship.

The Harmattan was a tramp steamer from the Harrison Line. That was Harrison’s of London, not to be confused with Harrison’s of Liverpool. It was one of the oldest British shipping lines of its type, the stuff of which the mercantile traditions of the Empire were made.

The company’s symbol was big red H in a black ring and on this ship it was painted on its single smokestack. The Hungry Harrisons they called the line, and for a reason. It wasn’t much of a ship, a scrounger of maybe 6,000 tons that lived by its wits from port to port, eking out a living, anchoring off a port and waiting for a cargo.

For signing on to the Harmattan Bill Marshall, new ordinary seaman, was given 10 shillings, which was two weeks pay. With a full pound in his pocket he went out for a night on the town in Portsmouth, and spent just about all of it. First stop was the Portsmouth Hippodrome, where you could sit in the gods for tuppence, smoke a few Woodbines and watch the show.

Then he went to a pub, flirted with some young girls, buying them shandies while he settled in to a session with four or five `Brickies’, little bottles of strong barley wine. A round of smoked salmon sandwiches took care of the hunger. By the time he went back to the ship he was more than a little drunk.

The next morning the Harmattan set off for Newcastle. It would take four or five days to get there, traveling `light ship’ or empty from Portsmouth. In good weather they could make 12 knots. It occurred to him they were going the wrong way for Australia.

Young Bill Marshall had read up on travel to Australia. It took six weeks. That was on the kind of ship his father used to captain before the First War. But this was a tramp steamer, and Bill was off on a round the world trip that would take 18 months, not six weeks.