Risotto, Genoa, the 1950s, Milton on Tariffs and an Italian Immigrant's story.

April 12, 2025 Volume 6 # 2

A Fisherman in the Harbour at Camogli

A heron sitting on a small fishing boat waiting to catch a meal.

And Risotto with cuttlefish ink and squid at a restaurant 10 yards away

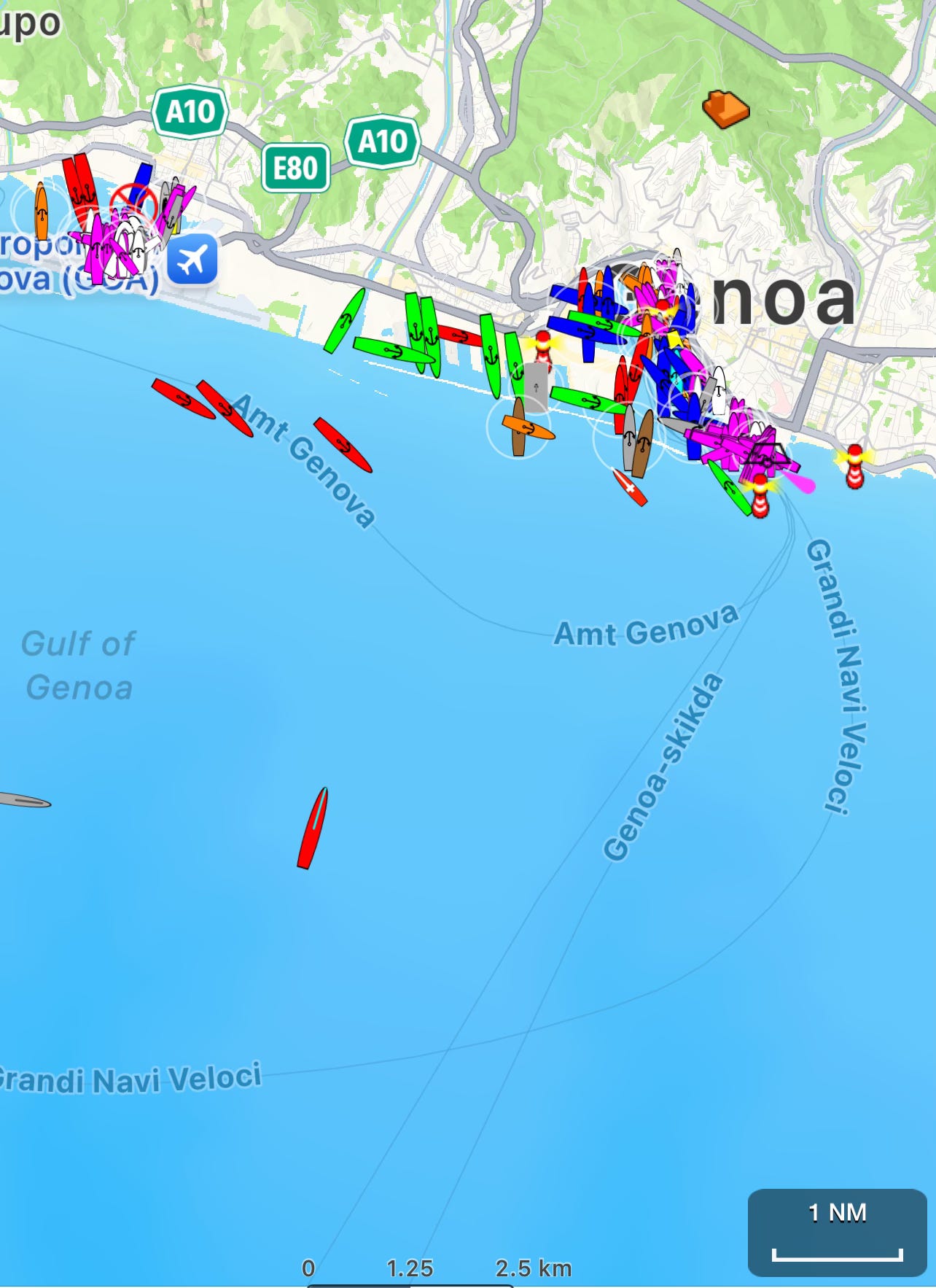

Genoa: The Port City, Home to Christopher Columbus

Genoa is the busiest port in Italy and one of the most important in the European Union. Its harbour, part of which you can see from the air, is crowded with cruise liners, container ships and tankers. Genoa is rougher than sleek Milan, just two hours away by train. To give an idea how crowded the port is, here is a scan from Boat Watch, an app that tracks the movement of ships.

The seat of the Republic of Genoa, once a powerhouse in the Mediterranean. The rich architectrure, like Piazza De Ferrari in the centre of city are a reminder of its wealth.

Genoa and the Italian Riviera Were Once Part of the Holy Roman Empire

“The Holy Roman Empire was neither Holy, nor Roman, nore and Empire,” Voltaire in 1756, 50 years before Napoleon dissolved it.

This map shows the Holy Roman Empire at its peak in 1250 the last year of the long reign of Frederick II, who spoke German, like this map. Genoa then included Pisa, Corsica, tiny Elba and Corsica and colonies in Syria and Crimea, among other places. Lots of interesting bits around the edges of the Holy Roman Empire. Poland wouuld disappear for a while. Prussia, which led Germany in both World Wars, is just a speck around the outer edge. Friesland, in the yellow next to Holland, is now just a province of the Netherlands, with a separatist twist, and Fries is probably the closest related language to English. Serbia is huge, the cause of unending resentment, as is Hungary.

Tourist Talk…and Reality

Americans, and Canadians, like three countries in Europe.

Europeans prefer to visit, New York, Florida and California.

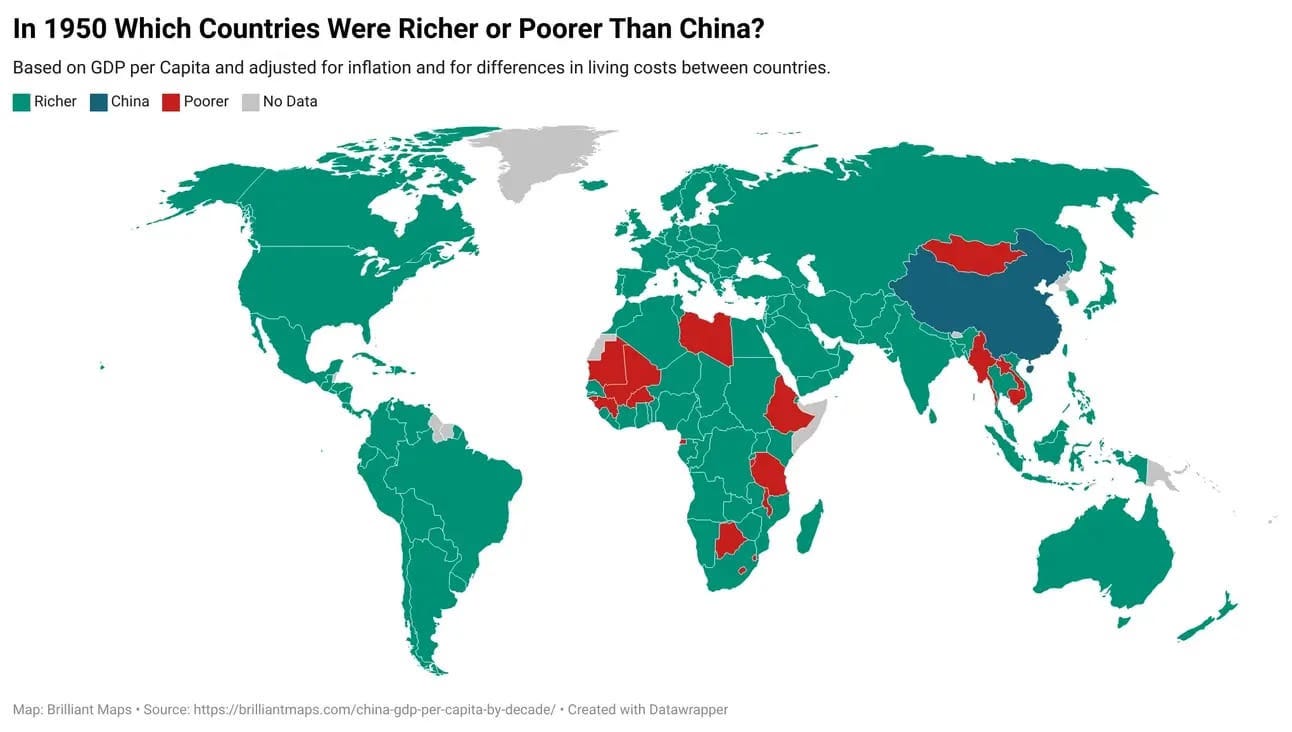

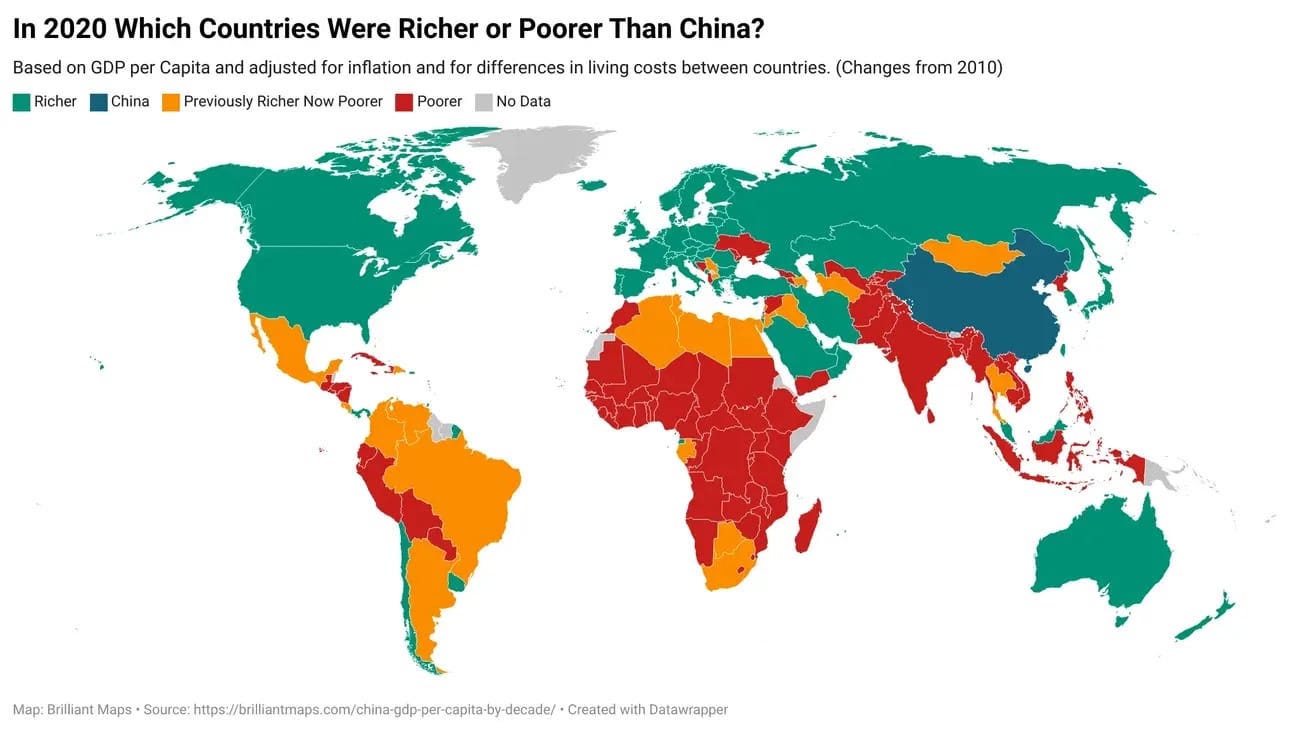

China Then and Now

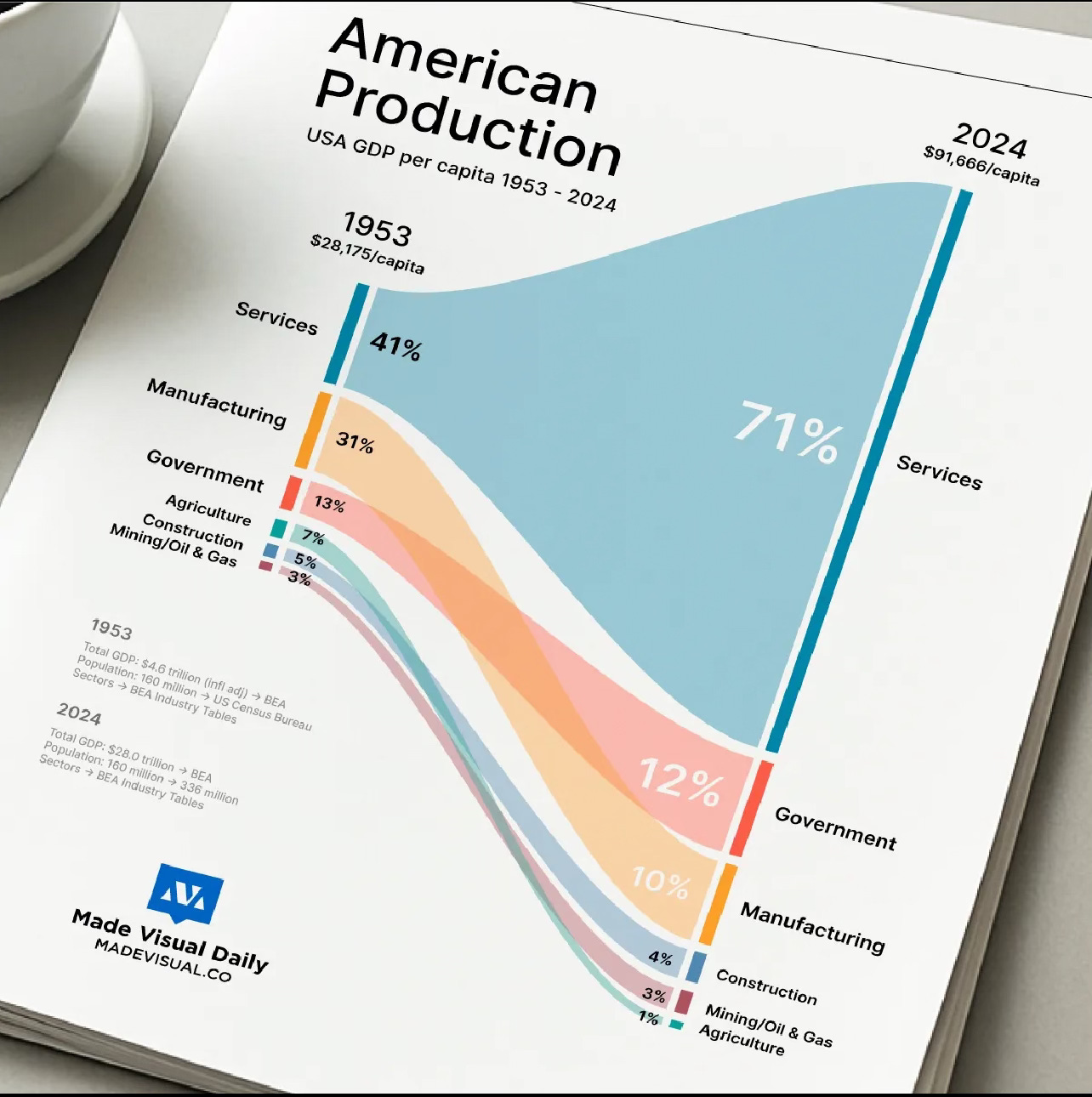

Why the 1950s Aren’t Coming Back

Manufacturing was one job in three in the United States in 1953. Now it is one job in ten. Services can mean a lot of things, working for a bank which is well paid, or working for Starbucks or McDonalds, which is not. It will cost Americans a lot of money to bring back manufacturing jobs.

If iPhones were made in the United States, they would cost $3,500 instead of $1,000 says an article in Barron’s on Friday. It suggested Apple may have to cut low end iPhones and introduce them every two years instead of every year.

But on Saturday, Barron’s said smartphones will only pay a 20% tariff.

A robotic weeder uses Artificial Intelligence to know the difference between a crop and a weed. Few people work on farms in the United States, just one percent of the population, down from seven percent. It’s automated and they produce more food.

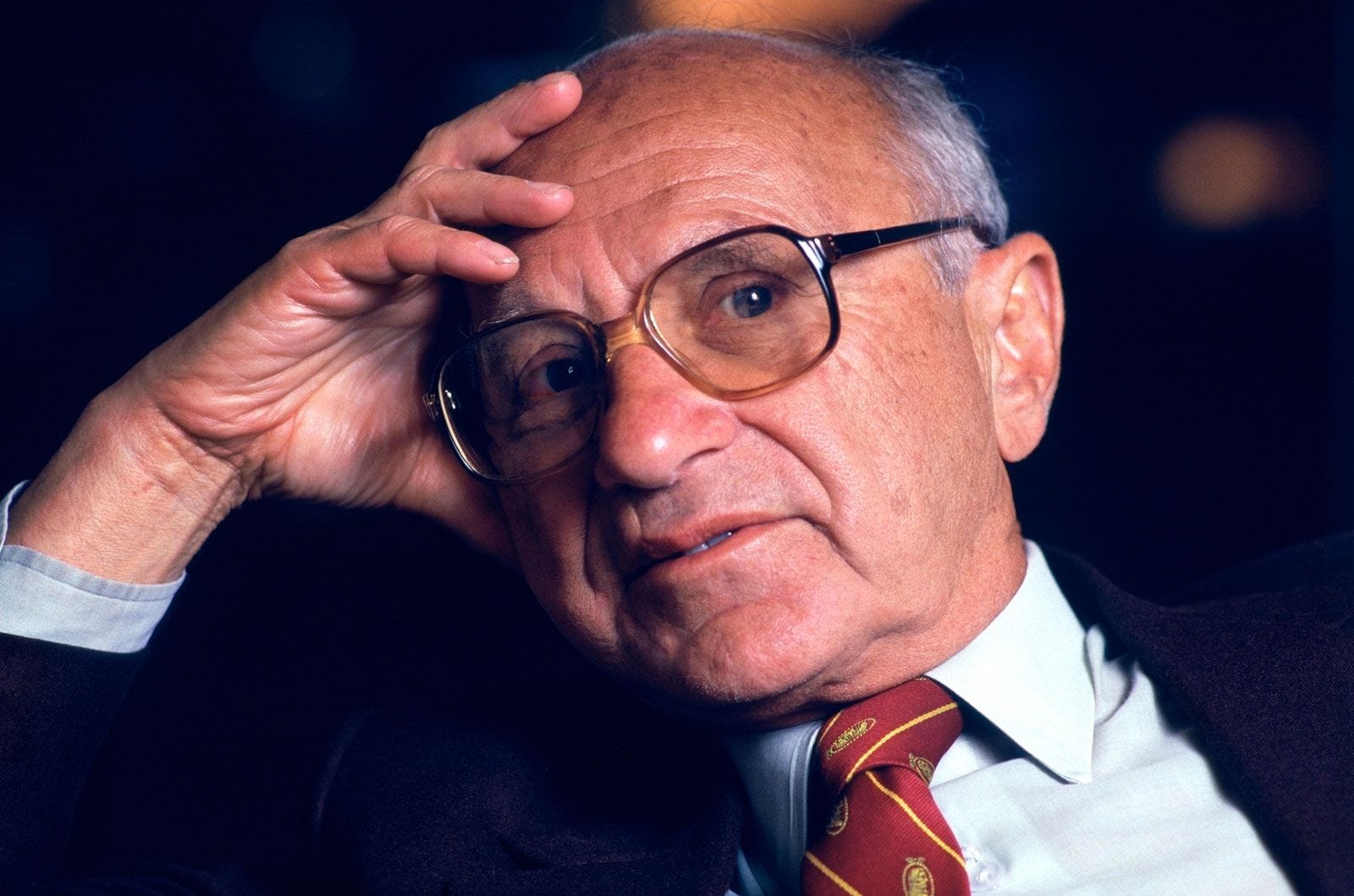

Milton Friedman on Tariffs

You might think Milton Friedman would be popular in a Republican White House.

But the free-market economist, who won a Nobel Prize, was not a fan of tariffs.

These two clips are from a speech he gave in Kansas in April of 1978.

“The political reason (for tariffs) is that the interests that press for protection are concentrated. The people who are harmed by protection are spread and diffused. Indeed the very language shows the political pressure. We call a tariff a protective measure. It does protect; it protects the consumer very well against one thing. It protects the consumer against low prices. And yet we call it protection.”

When Friedman gave that speech it was Japan, not China, that was the country the politicians said was taking advantage of Americans. Friedman said bring it on.

“What about the argument of unfair competition? What about the argument that the Japanese dump their goods below cost? As a consumer, all I can say is the more dumping the better. If the Japanese government is so ill-advised as to tax its taxpayers in order to send to us, at below cost, TV sets and other things, why should we as a nation refuse reverse foreign aid?”

Click here for Milton Freeman's speech.

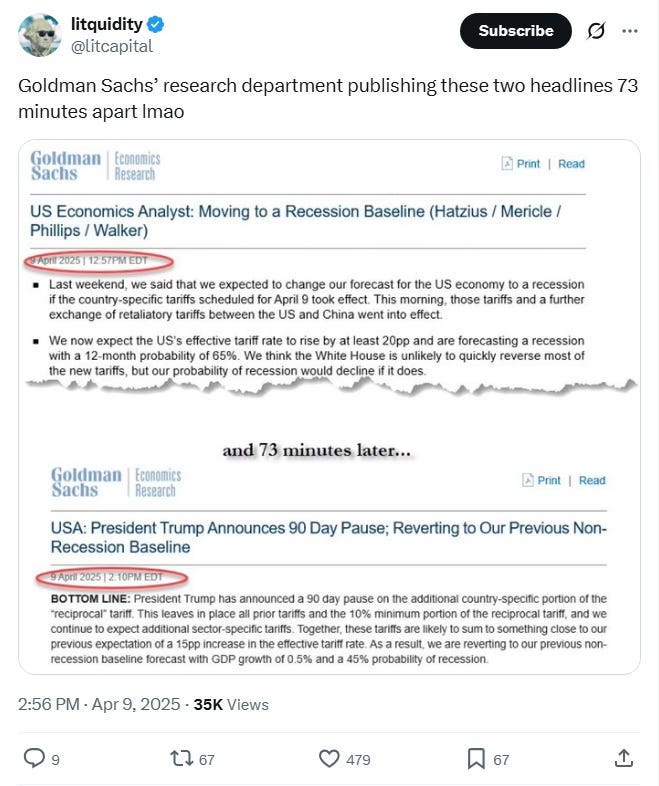

The On Again Off Again Recession

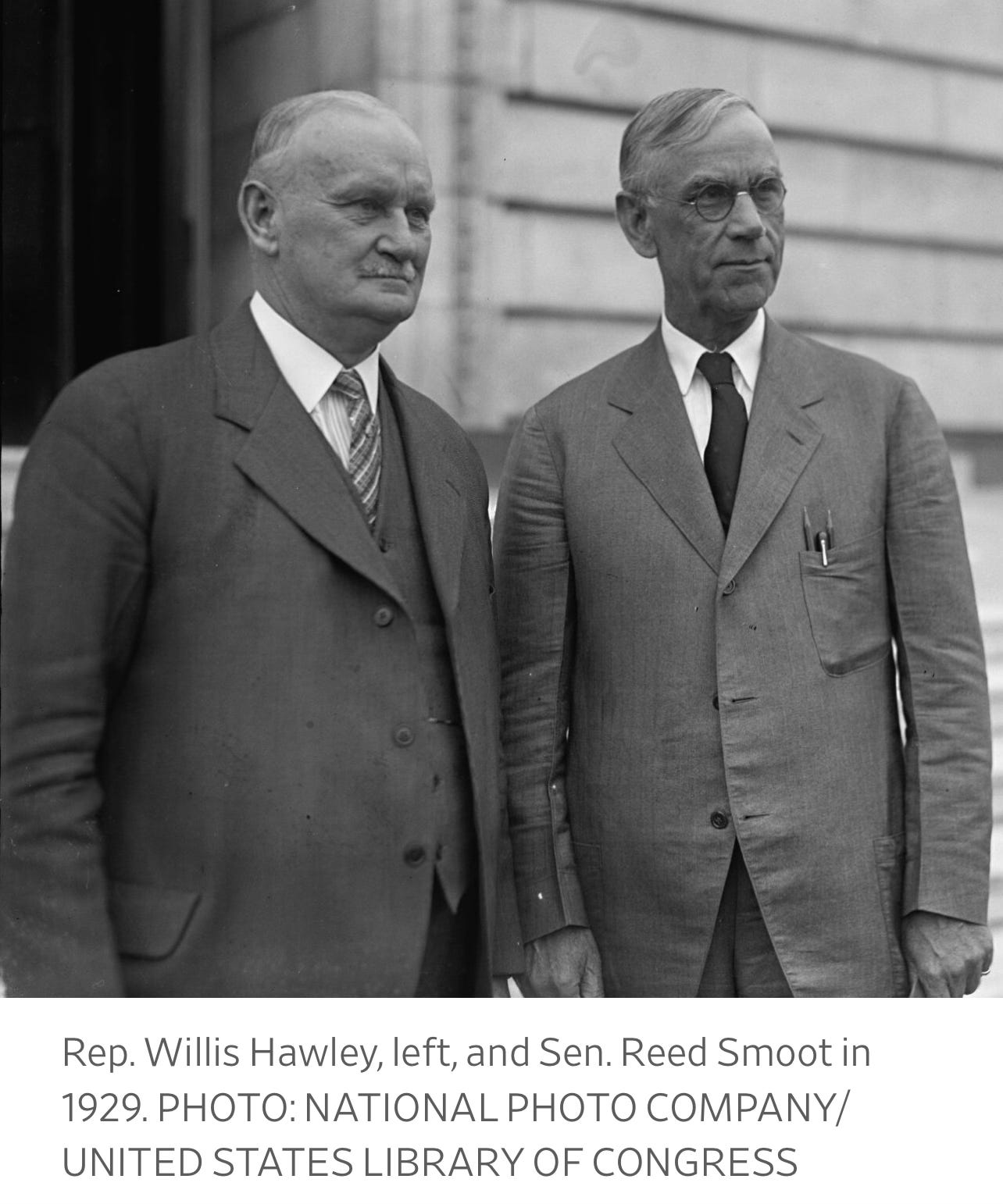

The Two Bozos Who Started the Last Tariff Crisis

The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of June 1930 was designed to protect industries, workers and farmers in the United States. Instead it added to the chaos of the stock market crash of October 1929. By 1933 the American economy lost almost a third of GDP, unemployment went from 3% to 25% and 85,000 businesses went under. Half of the mortgages in the US were `delinquent’. The depression spread to the rest of the world, inlcuding Germany, where it helped elect Adolf Hitler.

Sun sets on a Catamaran Off Liguria

Essay of the Week

This is another chapter in the life of Louis Aldrovandi. I was the ghostwriter. After the book was published Louis took it to Italy and had it translated. The translator listed himself as the author. Cheeky, but what difference does it make? One thing he couldn’t translate was my title: A Lift to Life. It was a play on words, a reference to Louis’s company, LiftKing. It defied an Italian equivalent. Here is the Italian cover:

Louis made the basis of his fortune as a young man working in hydroelectric contruction sites in the north. Later he worked in South America, by then an experienced hand, and put away more money. He was a saver, didn’t drink at work and stayed away from the poker table. He grew to love the north. And though he started as a mechanic, he soon became a manager and travelled the world. Part of the reason for his success was the Italian school he went to didn’t just teach mechanics, they added literature and philosophy. Louis was a cultured, civilized man. Later he started a major company, and like most immigrants, bought land. Louis once told me about a 10 acre piece of land he bought on what was farmland outside Toronto. “When I bought it they measured in acres. Now they measure it in square feet.” The municipality wouldn’t let him build. So he kept the land and paid farm taxes. Around his slice of land, grew the city of Markham, one of the richest suburbs in Toronto.

Here is this week’s chapter.

Carillion Then New Zealand

Once back in Toronto, I had a few days of rest and then I went to the McNamara offices. At the risk of being immodest, I have to say they were effusive in their praise about how I had turned things around on the Kelsey project, helping change it from a money-losing project to a profitable one and pushing it ahead of schedule by a year. McNamara paid me four months in advance to go back.

However, Roy Anderson of Perini kept calling me asking if I wanted to go and see a job he called the Carillion Power Project near Montreal. I went there in November and he hired me right away. A week later I started working in Montreal.

There was a quick trip back home to ready the family for the move. By the third week I had rented a house in Dorion in the same subdivision as Dick Boivin. Dorion was convenient. It was half an hour drive on the old number 2 highway into Montreal and about forty-five minutes along highway 17—the road to Ottawa—to the site at Carillion. With Dick as a neighbor, it meant he would drive one week, I would drive the next.

At Carillon the Ottawa River drops about 65 feet (20 meters) and there was a canal built there in the nineteenth century. Hydro-Québec planned to tap the huge flow of the river and produce electricity. The construction job consisted of a building a concrete dam across the Ottawa River from Pointe-Fortune, Quebec, on the west side and Lachute, Quebec, on the east. There were two separate groups although only one manager. Each side had a construction supervisor and a hiring office. This was just on the Quebec-Ontario border. By now I was at home in both and could deal diplomatically in the two languages of my adopted country.

I was in charge of the mechanical departments on both sides of the river. Since it was a government job it meant the workforce was unionized so we were working only five days a week, eight hours per day. It was the most restful period that I had ever had. I had a short commute back home to Dorion so I had all the time that I always wanted for my family.

It may have been peaceful, but there were some crises on the job. One of the biggest problems was a man named Whitton who was in charge on the west side of the river near the Ontario border. There is no way round it: he was an old-fashioned extremist of the kind I had run into the work camps in northern Quebec. He didn’t like French Canadians and was positively rude to the Hydro-Québec people.

There was also a major construction accident. A temporary Bailey bridge had been built across the river. It was a military design used to connect one side of the river to the other. One day it collapsed killing a crane operator.

I left Montreal after seven months for a vacation to Italy with the family. Before we left, I knew there was a chance I might have to go to New Zealand and start yet another new job. I confirmed this by phone while I was in Italy. The equipment needed to start the construction job in a joint venture with a local contractor was shipped to Auckland on a chartered ship. I was advised of the ship’s arrival in Auckland and asked to be there to unload the equipment from the freighter called the Hong Kong Clipper.

The equipment was on a slow boat, but I was going by air. Back then there were no direct flights, so I was going to hopscotch across Asia to get there. It turned out to be the most interesting and educational trip I had ever taken.

The flight to New Zealand was a whole new experience for me as I flew first class, a company policy for managers. On my way down, I planned on making a few additional stops; the first one was Calcutta, India. I only spent three days in Calcutta, but this was long enough to experience the misery and human suffering that these poor people faced every day. I saw a man dying of malnutrition in the street in front of my hotel. The poor soul was trying to bring his frail body to a nearby tree where he could lie down under the shade to keep cooler. When I asked the hotel personnel why no one was helping him, I was told that it was better to leave him to die and that, once the sun grew stronger, he would. Later on, two or three people dragged his body to the edge of the asphalt and left him there. In the early mornings, horse-drawn carts would drive down the roads and pick up the dead bodies and take them to a crematory. The crematory was listed on a tourist brochure as one of the things to go and view.

Next, I flew to Indonesia, a place as exotic and strange as India to a boy from a small town in Italy. From there it was Sydney, Australia, which was another former British colony like India, but what a difference. This was a modern city, quite a lot like I was used to back in Canada. Then it was on to Auckland, which is 1,300 miles (2,150 kilometers) away, almost exactly the same distance from Toronto to Winnipeg.

Before I begin to describe the job, let me tell you I was very impressed with New Zealand. To me it seemed the best country in the world: beautiful scenery from mountains to beaches, and the friendliest people.

We arrived in Auckland on a Sunday evening in May 1960. From the airport, I took a taxi to a good hotel, the best in town. As I arrived at the reception desk, I asked the lady for a room. She asked if I had a reservation and my answer was no, and I told her I was arriving from overseas, she turned to another lady and said, “We have a person from overseas without a reservation.” This was a big surprise to them that I would travel this far without a reservation; however, I indicated that I was in need of a room if she had one vacant I would let the taxi know and release him; if not, I would go elsewhere. I got a room on the second floor. One odd thing was I noticed there were a couple of lumps in the bed. Turned out these were hot water bottles to warm the bed later. A first for me.

There were other men from Perini Auckland working on the same job. The problem was that I did not have the name of the hotel where they were staying. Once in the room, I looked in the telephone book and found the name of the company with which we were working. The owner answered and I introduced myself. He already knew my name and told me where Dick Boivin and Don Duncan were staying: the Papatoetoe Hotel in the suburb of Papatoetoe. It was a strange Maori word and my New Zealand history was a little shaky to say the least.

Duncan was surprised that I had finally arrived. It was his birthday and they wanted me to go there as there was a party going on. They gave me directions for the taxi. Now I had to go downstairs and explain to the two nice women on the desk that I was checking out. They were most gracious and didn’t even charge me for my short stay. I called a taxi and went to the Papatoetoe Hotel 12 miles (20 kilometers) away.

The next morning, Duncan was going to Australia and then to Canada. I took over his rental car and suddenly there I was on my own driving on the wrong side of the road; however, I did well once I entered a street and turned against the traffic. I learned in a hurry.

The construction job was a motorway from the airport to Auckland, the first modern highway built in the country. My first task after unloading was to see that the equipment was assembled before moving out of the port and keeping an eye on the convoy to the job site. From there we had train the operators who had never seen such heavy equipment and then advise Perini and more of instruction of what was there for me to do.

The ship arrived and the unloading process started. Due to the limited amount of equipment in the port, however, our equipment was unloaded only when the crane was available. On top of that our ship had not been a regularly scheduled ship line, so that added another wrinkle.

It took a few days, but soon I learned the ways of the local workforce. First, I asked the port authority to give priority to unload our crane that was nearly all assembled. Once I achieved this and I had a crane operator hired, I started to ask for the permission to use our crane to unload and assemble our equipment. How it worked was, in the morning, as soon as the port crane moved to unload another ship, I formally went to ask the director of the port for permission to use our crane. The director then asked the union and once I received okay from both, I went to do my job. I followed their instructions and I asked for very little crane time, maybe half an hour to an hour. This comedy was repeated every day both morning and afternoon.

Everywhere in the English-speaking world at the time the unions representing longshoremen and stevedores were tough and powerful. Remember the famous Marlon Brando film, On the Waterfront? This was certainly true in New Zealand. The unionized workforce was mostly from England and the country was very socialist. I had to find a way around it and I did.

The project was to build a highway (they used the British term motorway in New Zealand) from Auckland, the largest city in the country, to its airport. It was a $40-million job and Perini had the personnel and equipment to complete it in partnership with a British contractor. There was a local New Zealand contractor, but he didn’t have the experience at this stage as there were no divided highways or motorways in the country.

The motorway was built in time. We (Perini Quebec) had a lot of equipment for the job. The intention of the joint venture with the local contractor was of course to do more construction work, but the possibilities were limited due to New Zealand’s small population. There were just 2.4 million people in a country the same size as Britain. There were ten times as many sheep as people. The Aldrovandi family almost moved to Zealand, but it didn’t happen. Think, we could all be speaking with Kiwi accents.

Once the equipment operators were trained and all of the most important details of the equipment were pointed out to the mechanic, I was ready to leave when I received a telegram from Perini to get ready to move my family to New Zealand. My answer was that there was there was no need for me to stay. Boivin could handle it on his own.

My stay wasn’t quite over. There were a lot of unique things about New Zealand at least for me. At the time, New Zealand had the most bizarre drinking laws. Bars were open from noon to five in the afternoon then everyone had to drink up and be out by six. On afternoons you would see with a table full of glasses of beer and they would all be gone by 6 p.m. If you wanted a drink at night, you could go to one of the private clubs, knock on the door, and say you wanted to join, and purchase a membership. Then you could spend the night drinking and dancing without being bothered.

It wasn’t just the drinking laws that were odd. Before you could leave New Zealand, you had to go to the taxation office and get a tax release to exit the country. This could take a full day.

The day before I left, I had all the tax problems cleared up and my Kiwi friends threw a going away party for me at a beautiful house at top a small hill. The party was a bit drawn out—it lasted until 1 a.m.—and after it I drove my rental car, a Holden made by GM in Australia. I shouldn’t have driven, but I did. To make a long story short, going down the hill on a very tight curve, a car was coming up and hit me, which really shook me up. There was a lot of damage and I suffered several cuts and scratches on my face and my eye was swollen shut.

The police arrived and asked for my I.D. and asked me many follow-up questions such as when was I planning on leaving the country? I knew that if my answered the truth, my passport would be taken away. Therefore I said that I was hurt and I did not know how long it would take for me to feel better and added that I needed to get to a hospital as soon as possible. It wasn’t until 3 a.m. when the doctor visited me, took X-rays and cleaned me up by 5:30 a.m. I left the hospital in a taxi for the hotel. I said my good-byes to the hotel owners, Boivin, and the others. I got my suitcase and Boivin drove me to the airport. The 7 a.m. departure was delayed and at every announcement, I was afraid that it would be for me. If the rental car or the police knew that I was leaving, for sure my departure would be stopped. It was a relief when the plane was prepared and we were on the runway ready for takeoff—but then the engine stalled. Back to the hanger we went where we were informed that the fuel pump shaft had broken and that we were going to be delayed another two hours. By the time the parts needed to fix the plane, it ended up being closer to a four-hour delay.

The aircraft was an old Lockheed Electra and most of them had been taken out of service because they were unreliable. It was a terrifying trip, with such extreme turbulence that parts of the wing dropped off and fell into the ocean. An ugly end to a visit to such a beautiful place. Finally we made it to Sydney.

To show you how different the world was back then, I arrived in Australia with only New Zealand pounds. The first bank I went to said they could only change £12. And these two countries were neighbors. After a bit of negotiating in the manager’s office I cleared that up.

I stayed in Sydney for a few days before heading out on another cross-Asia tour. Singapore was one of the most interesting stops along the way. It was bustling and hinted at the huge international success it was to become. The country was shopper’s paradise with things such as Japanese cameras and transistor radios that were much more expensive back in Canada. Apart from the shopping, there was also the multicultural aspect of the city-state and how it had managed to smooth over differences that caused so much trouble elsewhere.

Our plane took us on to Pakistan and then to Rome. I went north to pick up Gianna, Mark and Grace and then returned to Montreal.