The Weekly Market

The Italian towns of Liguria have at least one weekly market and some of the bigger ones have two. Camogli has one every Wednesday. Above, Bar Baby, my spot.

It stretches about a two thirds of a kilometre from the train station, just over the shoulder of the woman below with her black spaniel on Via XX Settembre, which celebrates the capture of Rome and the Papal States on the 20th of September 1870, completing the unification of Italy and making Rome its capital. Popular in the north, in the south not so much.

It meets a little park with its statue of a local fisherman who was killed fighting with Garibaldi. The sea where he fished is behind him. He should have stayed home.

Here the street takes on another patriotic name, Via Della Republica, more Garibaldi won propaganda. History is forgotten on market day, though. Better to stick to selling wine with the Mediterranean as a backdrop.

My favourite stall

The most amazing collection of socks. Almost all of them made in Italy and two pairs for 10 Euros. I have over bought and my sock drawer runneth over.

Gold

Each of those gold kilo bars is worth $105,000 as of Friday May 2. Handy size for a quick getaway. Though it would set off the metal detector at the airport.

The small investor is all-in on gold, according to a report by the World Gold Council, though they don’t actually put in those plain words.

Individuals are buying gold coins and bars and gold ETFs, Exchange Traded Funds. I have a gold related investment and it has done rather well.

The report says Central Banks are still buying but not as much. Ditto for jewellery.

With gold touching $3,500 an ounce in April, gold bangles became too pricey and the Gold Council predicts demand for gold jewellery will drop. Gold was $3,247 on Friday.

China and India account for more than half of world demand for gold jewellery.

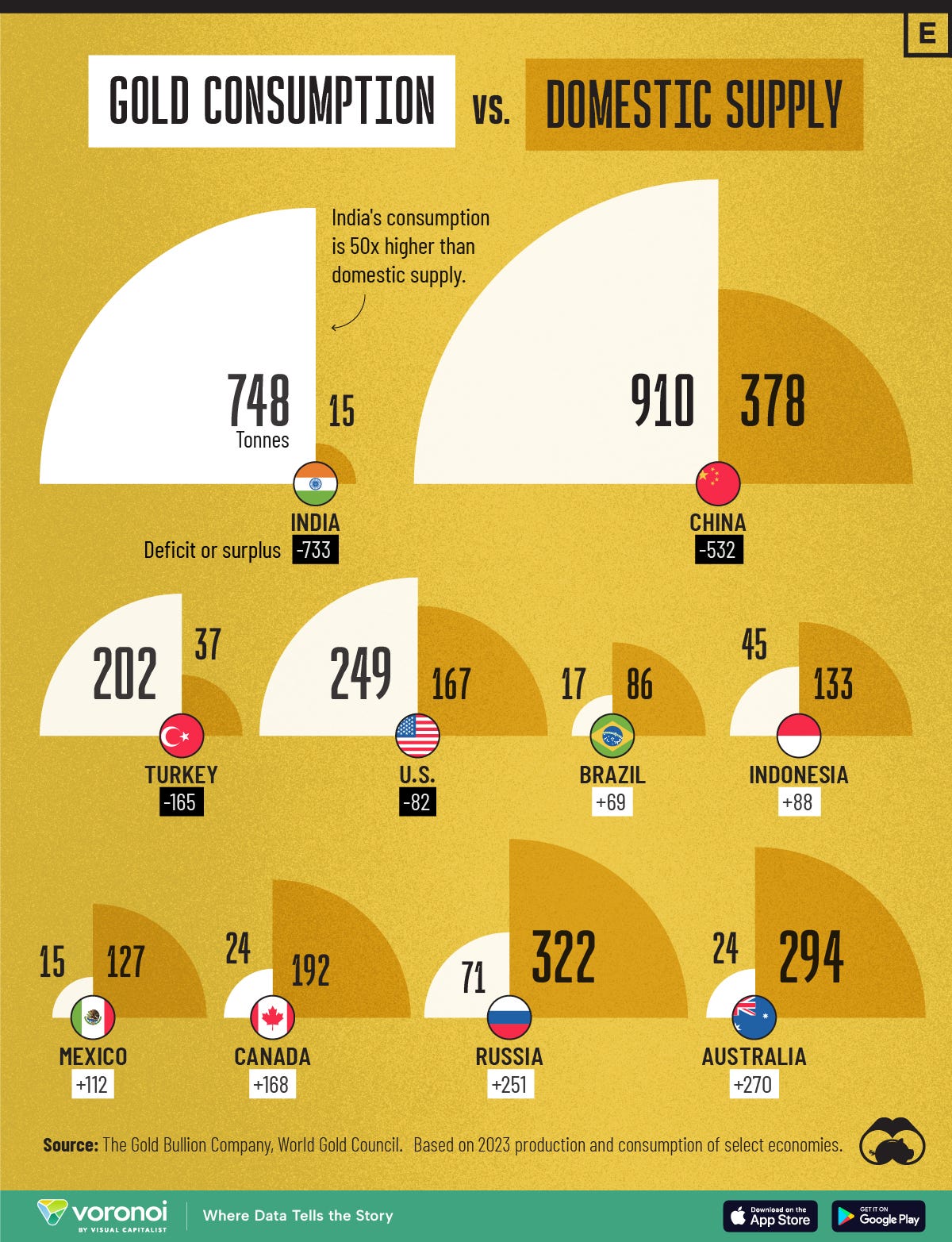

Countries that produce gold aren’t always the places where people wear it.

Here is a link to the entire World Gold Council report.

The Prisoner and His Lotus Super Seven

When I was in my 20s I really wanted one of these. The Lotus Super Seven was a street legal racing machine. It was driven by Patrick McGoohan in the opening scene of The Prisoner, a weird spy drama that ran in 1967-68. The Super Seven was designed by Colin Chapman of Lotus fame. It weighed next to nothing and could do zero to sixty faster than most sports cars of the day. It handled like a motorcycle. Grossly impractical but very cool.

Essay of the Week.

This is another chapter of the book on Sam Ciccolini, the story of his business success.

Chapter 9

The First Insurance Agency

When people look at Sam Ciccolini today, they might say, “What a successful guy. I guess getting there was easy for him.” Well easy it was not. It started when Frank was selling life insurance and Sam was still working on contract for the engineering firm.

Frank found out that a friend of the family, Steve Perzia, wanted to sell his small insurance agency. Seems Steve had been trained as an architectural draftsman and figured he could make a lot more money doing drawings and getting permits for all the garages that were going up in the laneways and back alleys of Little Italy.

The agency was for sale for $4,000 and Frank wanted Sam to go into business with him. Neither had the money so that night at dinner they asked their parents it they could lend them $4,000. It shows how frugal Pasquale and Filomena Ciccolini were, that they could have that kind of money in the bank on a working man’s paycheque.

“My father looked at my mother and she looked at him and she said, ‘I think we should give them the money’ because she, and I keep on coming back to my mother, she was the brain trust of the family,” says Sam. “So Frank got in touch with Steve and told him that we were interested and my contract with the engineering firm was almost over and so was the position. So on September 20, 1966, we met with Steve Perzia and we shook hands and said yes we were interested.

Steve’s office was at 1224 St Clair West on the second floor of a bank known as the County Savings and Loan Corporation. There was another room for rent and Sam walked in and asked to speak to the manager. Out came a man he would know all his life: Con Di Nino.

“We sat down and he said yes, great, it’s $25 a week and so we went upstairs to see the room and it was six by nine. I said Mr. Di Nino this room is very small. He said what do you want for $25, furniture too? I started laughing. Now we had a room, we had an agency, but we had no furniture. I called one of my friends Frank DelCore and asked him, since he was moving, if he had anything we could use and he said he had a desk, two chairs, and a steel cabinet. So we bought all that stuff from Frank DelCore for nine bucks. I still have the desk and the two chairs. I got them refurbished and they’re at my house.”

October 1, 1966, was start of Ciccolini and Perzia Insurance; the brothers were $4,000 in hock to their parents and not a prospect in sight. They kept the Perzia name for continuity and to keep operating legally under his licence. It would be years before Sam took a salary from the agency. He started to walk the streets of his neighbourhood, banging on doors to see who wanted to insure their car or their house.

This was also the start of what is arguably the hardest working part of his life, which, when it comes to someone like Sam Ciccolini, is really saying something. He arrived at the insurance office every day 8 am and left around 5. He then went home, grabbed something to eat, and headed out to his paying job at Oshawa Wholesale at the Ontario Food Terminal on the Queensway.

The company was the wholesale distributor for all the IGA stores in southern Ontario and the near north, places such as Parry Sound. It was a different era back then and many small towns had IGA franchises run by local families.

Sam was part of an eight-person inventory crew that would go out at night and do an inventory of stores, driving hours outside the city to do the job. On the weekends the crew would visit IGA stores in far off locations such as North Bay or Ganonoque past Kingston. On weeknights he would finish in time to get home around three in the morning, grab a few hours sleep, and head into the insurance office. This went on for seven years.

Max Wolfe was the boss of Oshawa Wholesale, and he encouraged Sam and the other members of the crew to do a little overtime at the Food Terminal when they returned. That was extra money and Sam never turned it down.

“Max Wolfe would say, boys, anyone want to work overtime? To sweep the warehouse ready for the workers at 7 o’clock. I used to stay there for an hour which would give me two hours pay instead of an hour,” says Sam. “Then I actually started going on a Saturday morning and my job was to make sure that all the fridges full of bananas had proper gas flow and proper heating to turn the green bananas the right color. I did that two hours on a Saturday and got paid four hours.”

Back at the insurance agency, times were tough. In their first month in business they made $3.25. Good thing Sam was making $125 a week, plus overtime, from Max Wolfe at Oshawa Foods. The third Ciccolini brother, Livio, had joined the team while holding a job at Dominion Stores. It was sheer will power that kept the tiny agency going.

Most weekends were spent knocking on doors, most of them belonging to strangers. This is the “cold call” one of the toughest things to do in any line of work, but in particularly in the insurance business because most people think they don’t need insurance. It is a product that is sold, seldom a product someone goes out to buy.

There was also the kindness of people who wanted to give the struggling agency a leg up. Marino Di Nino, Con Di Nino’s father, was one of them.

“He was one of the pillars of our foundation apart from my parents because he kind of took me under his wing and said, ‘come with me, one of my friends needs insurance.’ So that was our first client, Diodoro Cocoa, and I think we still have him. He lived across the road from Marino on Hillmount Avenue and we went to see him and that was my first policy I wrote,” says Sam.

It wasn’t until 1972 that Sam left Oshawa Wholesale and started working full time at the insurance agency. His job was to sell and it still is. ( Today Masters Insurance has about 110 people working in its Woodbridge office and not one of them is in sales. The members of the Ciccolini family who work there, four of the older generation and ten of the next, do the selling.)“We are the sales force. We’re so highly oriented around our community that we never needed sales people,” says Sam. “We tried on two occasions to have sales people. Our first person to come and work with us was a fellow by the name of Mario Bonfini. That was in 1969 and he didn’t last very long because there was no money.”

But back to their first office on 1224 St. Clair West. It was 1972 and Sam and his brother started taking a paycheque of $100 a week with a bonus at the end of the year when the profits would be split fifty-fifty since each owned half the business. Along with knocking on doors there was non-stop networking, though sometimes the networking had nothing to do with selling insurance.

It was also the year Max Ciccolini was recruited into the family insurance business. He was reluctant at first. Unlike Sam, Max had been a star student at Harbord Collegiate and after graduating in 1965 went on to York University where he studied history and political science. Max was one of the first students at York University when the Keele campus began in 1965.

After graduating from York Max was accepted in law school at Queen’s University but left after a year. He was looking for a job when he was recruited by one of his former teachers to become a teacher himself. Soon he was teaching history at Danforth Tech. By the time Sam approached him to join the family agency, Max was making $9,800 a year with long summer holidays, a dental plan, and a pension. None of this was on offer at Ciccolini Insurance, as it had become known by 1972. There were 168 teaching days a year in Ontario high schools, while Ciccolini Insurance was a six days a week commitment or 312 days a year.

“In January Sam comes along and he and Frank had been in the insurance business for six years since 1966 and they had people working with them but as soon as they [the employee]realized that they could sell insurance on their own, they left,” remembers Max. “Sam said to me, ‘Max, if Frank and I are going to continue and go out and drum up business, we will need somebody in the office to do administration. I said, `Sam, are you crazy, I’ve got a permanent job with summer holidays, March break, Christmas and Easter.’”

There was another thing, the status of being the first member of the family to earn a university degree. “To Italians a ‘professore’ is status.”

We all know the outcome. Sam closed the deal. Max never stood a chance and he took a cut in pay—from about $200 a week to $125— gave up his benefits, and by September 1972 was on board at Ciccolini Insurance,

By this time Sam and Frank had moved from St. Clair Avenue, upstairs from Con Di Nino’s County Savings & Loan, to 1710 Dufferin Street just around the corner. When Max started so did a new bookkeeper, Josie Bertucci, who still works at Masters Insurance sitting right near Max’s office.

Max’s job was to answer the phones, handle the administration of the business, while learning as much as he could about the insurance business. A clever man, his academic training made him a quick study. It didn’t take him long to pass the exams and get his insurance licence. Max ran the office pretty much the same as he does today. That left Frank free to specialise in his side of the business: life insurance and health and benefit insurance, and let Sam concentrate on what he did best: meeting people, selling insurance, and networking.

With Max covering the office and the detail work, Sam went out to subdivisions that were under construction and lining up insurance on the new houses. Max says his brother Sam is “the best salesman in the family, by far.”

“Within two or three years by 1975 we had already built up a good book of business because they [Frank and Sam] hustled. Sam hustled every night and I would venture to say that out of every ten people that he went to see he probably wrote [sold a policy to] at least five of them. He had a fantastic hit ratio and that’s how we base our things even today. Companies quote a hundred and if they get twenty they’re laughing. So we were doing a lot better than the average at the time and that’s how we grew,” says Max.

One of the people Sam met was an energetic, ambitious young man, 9 years younger than Sam, who had moved from Windsor, Ontario, to Toronto. His name was Sergio Marchionne and, after graduating from university, took a job with Con Di Nino’s bank branch downstairs from the Ciccolini insurance office. Sam and Sergio would have lunch most days at the Harvey’s at the corner of St. Clair and Lansdowne. They would talk about everything except insurance, and for Sam it was a bit of an education and an eye-opener to wider world that, as yet, he knew little about.

Today Sergio Marchionne is CEO of Fiat Chrysler. He and Sam are still friends, and as Sergio travels and lives abroad, Sam keeps an eye on Sergio’s mother who still lives in Toronto. Back when Sergio was just a bank trainee, those lunches meant contacts for both of them in the local Italian-Canadian business community.

There was an important chance meeting at the Sidewalk Restaurant at the corner of St. Clair and Dufferin. The man they met was Emilio Gambin of the law firm Gambin & Bratty.

“So, Mr. Gambin asked, ‘what do you do, young man’? A staunch dignified sort of an individual who looked like he had just come from seeing the Queen. Very sharp and everything to the nines. I told him I was in the insurance business and he asked what type of insurance and I told him we had just started and we weren’t doing very well but we were going to stick it out,” says Sam.

That was when Mr. Gambin decided to give the young Sam Ciccolini a chance, not something easy, but a test to see if he could pull off a difficult task that his current insurer had trouble delivering. “He asked if we could produce insurance policies on the last Friday of every month and I said, ‘sure, why not’ but I was stretching the truth because I didn’t know what he was talking about. You see at that time they used to close deals on the last Friday of every month, they didn’t close deals every day or at three in the morning or two in the afternoon. He said you know every month we may close as many as two hundred homes and anyone who has a mortgage on the house we need to have an insurance policy. I said, ‘Mr. Gambin, I can do that with my eyes closed.’”

What happened next was the test. At the end of that month Mr. Gambin told Sam he would give him the closings and he provided the details of what his law firm needed.

Sam went back to the office and called the Boston Old Colony Insurance Company and Gibraltar Insurance and figured out how to work on the closings. What had to be done was to make sure the houses had insurance, and to do it all on the same day of the closing. It was complicated, and at first Sam, in his own words, “had no clue” what he was doing, but he learned and in a hurry.

“We got the names of the husband, the wife, the description of the house, how big the house was and which neighbourhood and whether or not there was a fire hydrant in front or it was close to a fire station. All that had to be part of the actual policy. Then I asked him [the insurance company executive] how much we needed to put on the policy and he said if the house is, say, 1100 square feet, how much would you need to replace it and that part I knew at around $20- $25 a square foot. The actual policy was for $8000 and I convinced him to take $2000 of contents and it cost $32 for three years.”

The deal was done late Thursday night and at 9:30 the next morning Sam showed up at the office of Gambin and Bratty with the five policies. The lawyer was dumbfounded. He had to pull teeth to get his regular insurance firm to deliver the policies by 3:30 on a Friday afternoon, close to the closing deadline. Bingo. Out went the other agency and soon the Ciccolini brothers were doing 80 to 85 closings a month, almost all the law firm’s business.

“It wasn’t rocket science. You had a four-page policy all with carbon copy paper and you had to type it but I had two girls at the time so I typed and they typed so we knocked them off in one day,” said Sam. “Now, were there mistakes? You’re darn right there were mistakes, nobody’s perfect but we actually did it. Of the four-page policy, one copy went to the client, one to your office and two you sent to the company. And we used to deliver them to the company so they could set up files and the company would actually give us a stack of policies with those red numbers in the right hand top corner of the page.”

Next Gambin and Bratty asked if Sam could do some legal work involving letters of credit that were stranded in Alberta, which was followed by work on bonds. It is a relationship that has lasted to this day.

“We do most of Bratty’s work and Remington’s [a subsidiary firm] work downstairs. They have our trust and Rudy Bratty is the most prolific lawyer/developer in Ontario, probably one of the biggest philanthropists that I know, and just a totally all-round great family,” says Sam.