Tariff Frenzy, Routes in the Age of Sail and a War Correspondent Who Covered the Nazi Surrender and the Trial at Nuremberg.

December 2, 2024 Volume 5 # 24

Tariff Panic

Donald Trump’s online musings about a 25% tariffs on goods from Canada and Mexico threw the chattering classes— journalists, pundits and politicians— into a panic. Markets, where people are putting up money, not words, were unmoved.

The Canadian dollar was actually up during the week, even though lazy headlines midweek said the tariff news had hit it hard. It barely budged after an early sell-off.

The Toronto Stock Market index closed at a new high. No panic here.

Trudeau to Florida

The Prime Minister embarrassed Canada by rushing to Florida to suck up to Donald Trump. Could you imagine his father Pierre doing anything like that?

Canada has a lot of bargaining chips. The country supplies the United States with oil, aluminium, nickel, copper, cobalt, potash fertilizer and many other products, along with its intricate involvement in the car business.

This is an ice-breaking freighter, the Umiak 1— note the bow— picking up nickel, copper and cobalt from the Voisey’s Bay mine in frozen Labrador.

This is one of the many car plants in Windsor one mile across the river from Detroit.

“Canada exports approximately 25% of its national output to the U.S., selling almost all of its oil there, while vehicles manufactured in Canada account for 7% of U.S. auto sales. On the other hand, Canada buys more from the U.S. than China, Japan, France, and the U.K. combined. I cannot emphasise enough the importance of these issues,” wrote the economist Hubert Marleau this week.

“Canada is not a weak and defenseless country and should not act like one,” wrote Conrad Black in this weekend’s National Post.

World Import Trade at a Glance

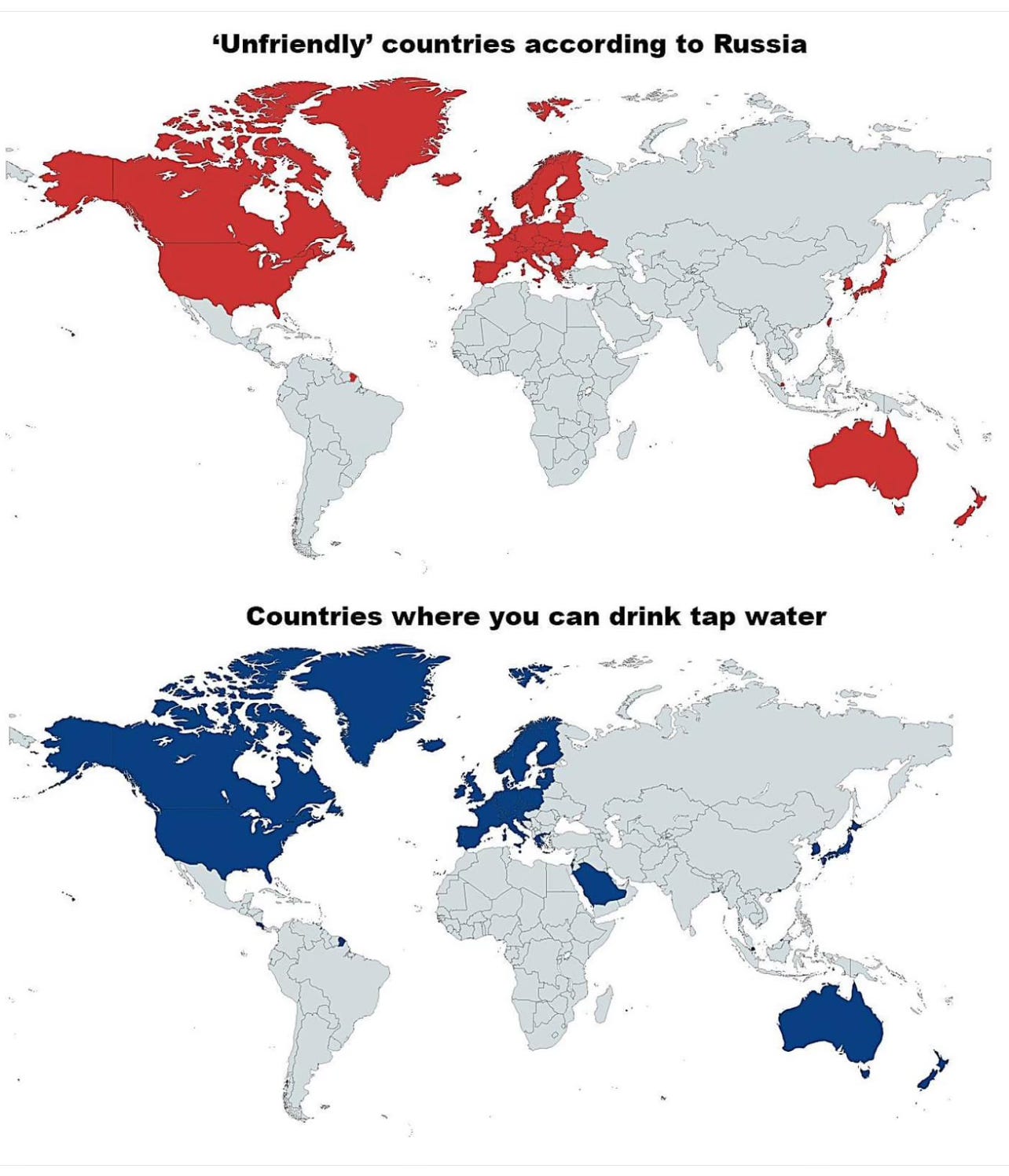

Weird Maps

No explanation needed.

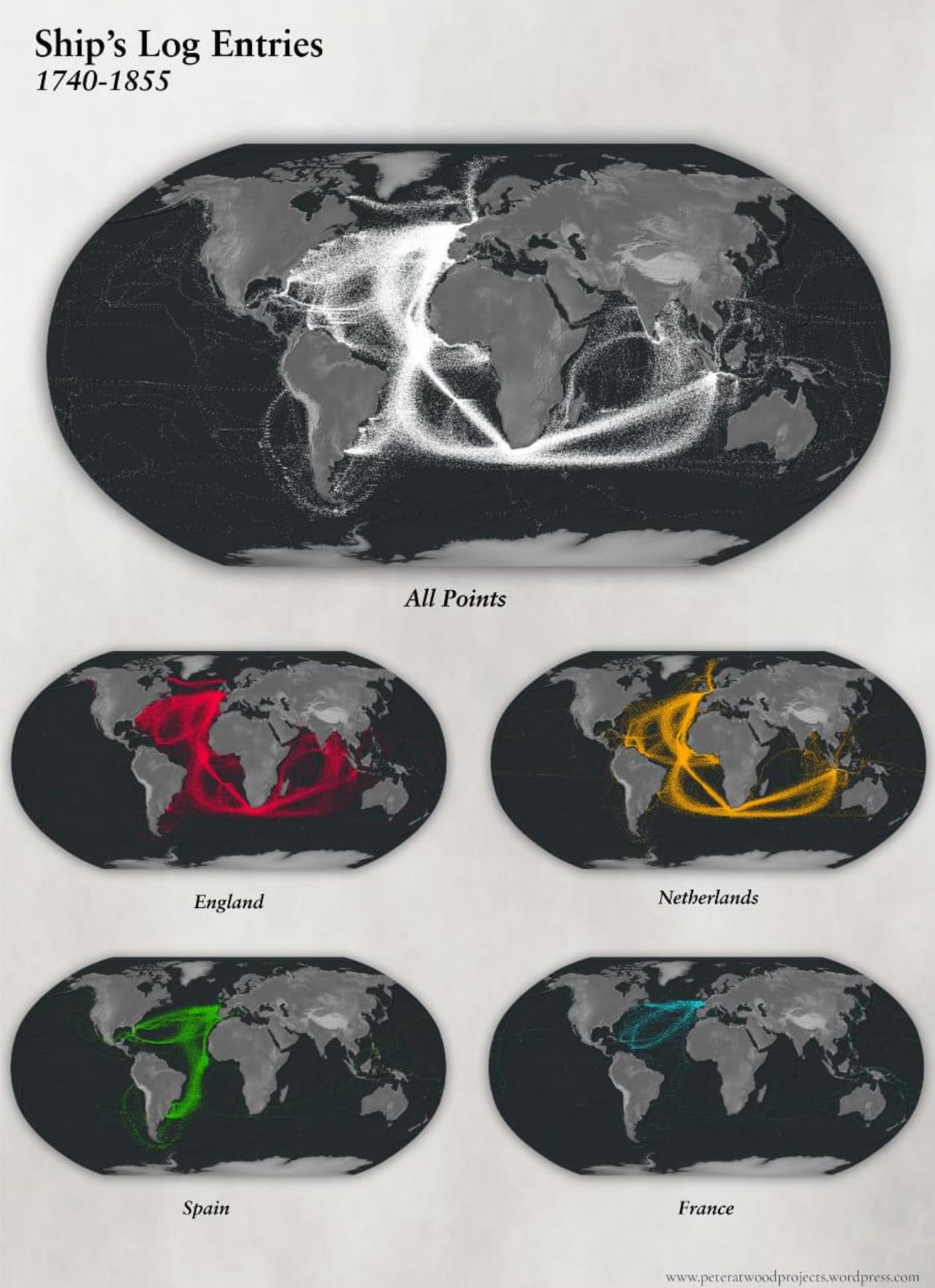

Routes of Sailing Ships

The maps below are from 280,000 log entries from the age of sail. The four big European colonial empires are broken down. England and the Netherlands seem to be the busiest; Spain and France concentrate on their American possessions. The can’t have included everything; there are no lines to Australia for instance.

And few ships braved Cape Horn, the deadly waters off the tip of South America. David Grann wrote The Wager, which talks about the hell of Cape Horn. Great read.

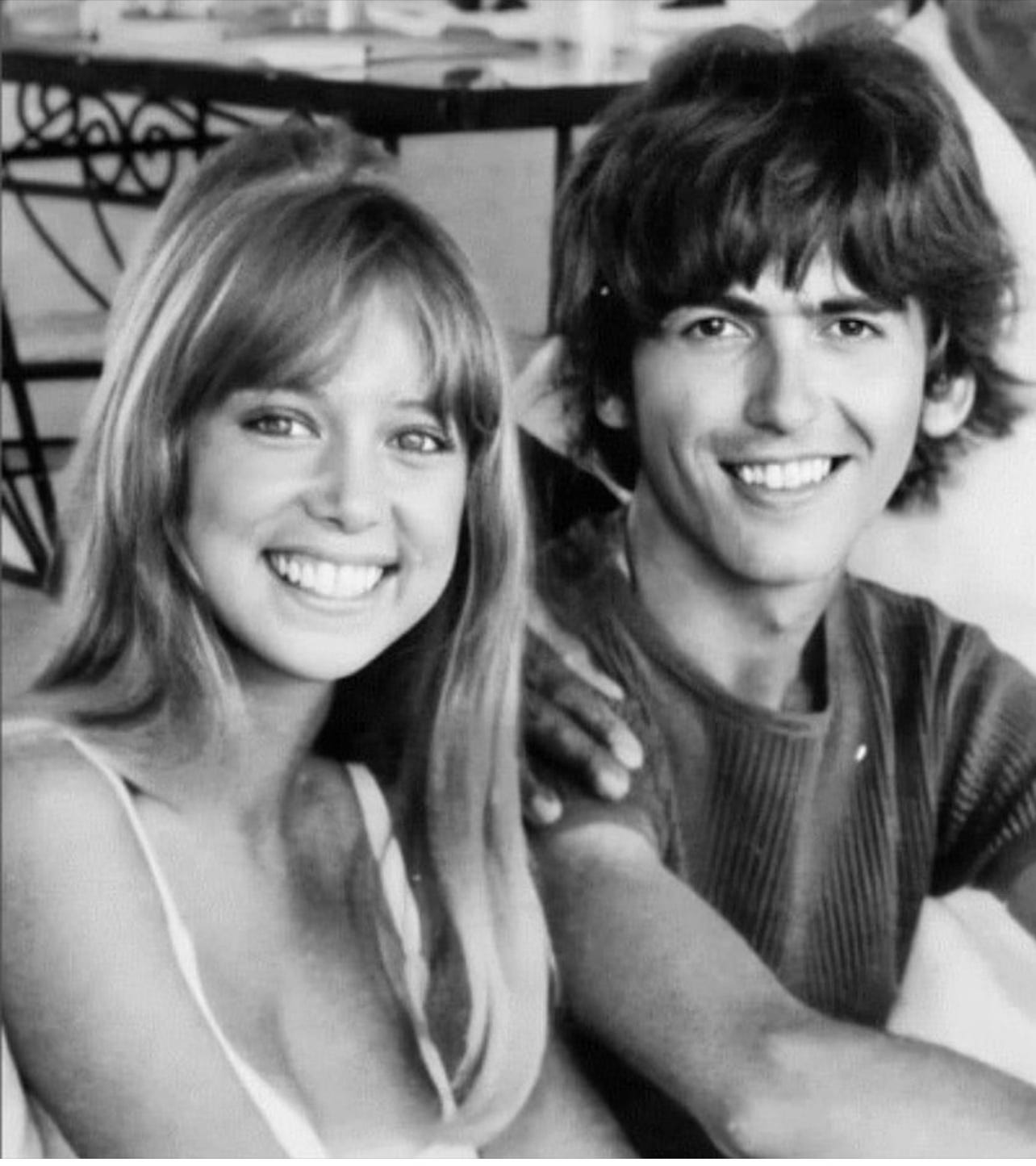

Beatles Love

Pattie Boyd and George Harrison on their honeymoon in Barbados in 1966. They remained married until 1977. Two years later she married Eric Clapton.

A Rare Sighting

I have never seen a Great Horned Owl, or just about any owl. A friend took this picture in the Morgan Arboretum in Senneville, Quebec, on the island of Montreal.

Essay of the Week

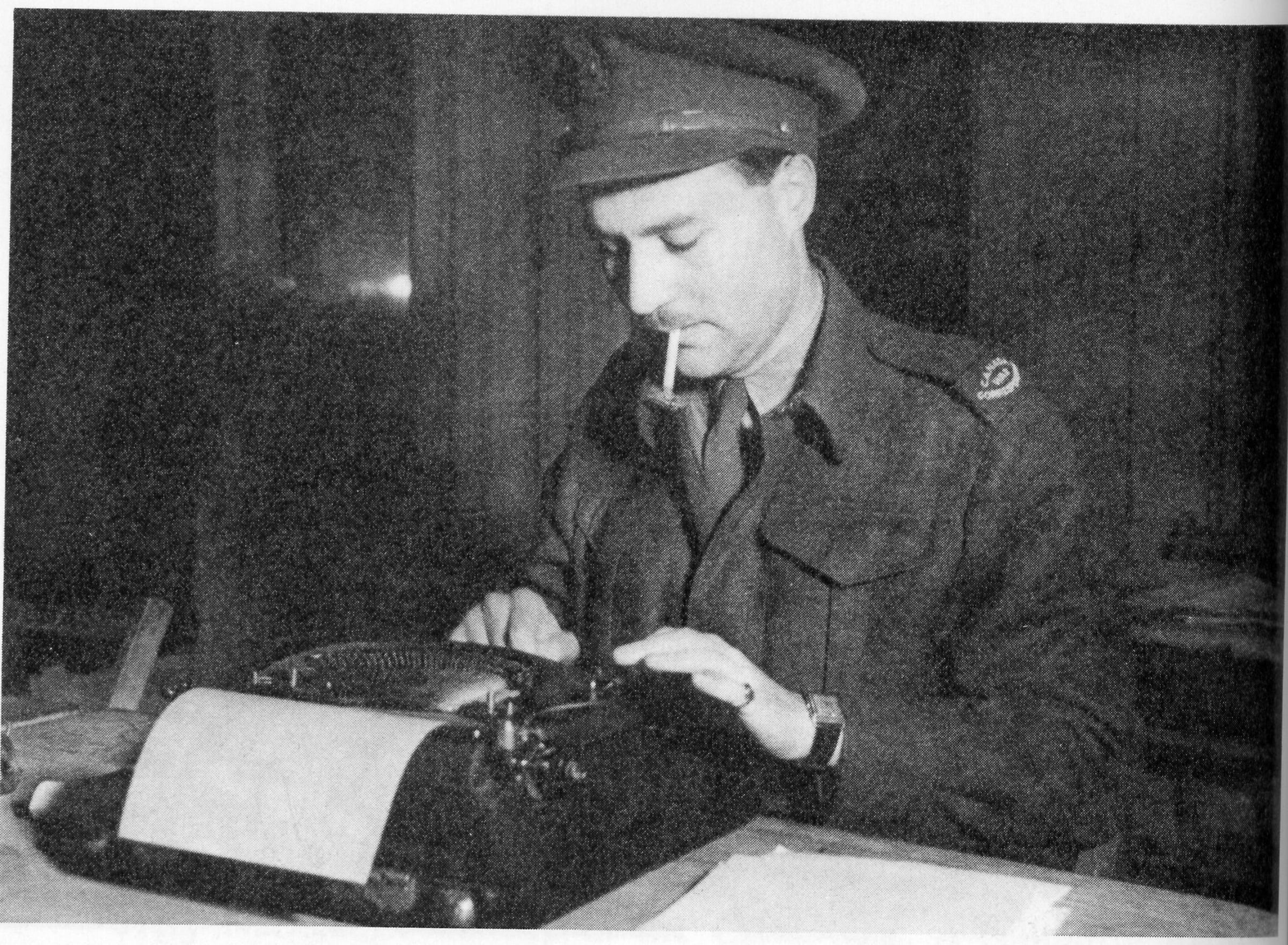

Gerald Clark was a dashing young war correspondent waiting in the bar at the Hotel Scribe in Paris for Jacqueline, a young woman he met during the liberation of Paris, almost 9 months earlier. It was early May of 1945 and a press officer from Supreme Allied Headquarters rushed into the bar and grabbed Mr. Clark.

“Thank God I’ve found you. We need a Canadian.”

A few hours later, after a short flight, Gerald Clark of the Montreal Standard and other select war correspondents watched General Adolf Jodl and Admiral Hans-Georg von Friedeburg walk into a room to sign the papers of Germany’s unconditional surrender. It was early in the morning of May 7, 1945, in Reims, the same French city where Adolph Hitler had danced his famous victory jig after the fall of France in 1940.

There were only 17 reporters present; the other Canadian Mr. Clark recorded in his memoirs, being Matthew Halton of the CBC.

“Jodl and von Friedeburg marched seventy-five feet along the cement corridor leading to General Eisenhower’s office,” wrote Mr. Clark. “Eisenhower’s blue eyes were glacial as he regarded the Germans who stood before his desk. In one sentence he demanded whether they understood and agreed to carry out terms of the surrender they had just signed. Jodl said, `Yes’.”

After the war when he told the same story to an audience at McGill, a dozen people in the audience wanted to know what had become of Jacqueline. He replied she was at the bar of the Hotel Scribe waiting for him the next night.

Gerald Clark covered the war from 1943 on, from features in pre invasion London -- where geographically challenged Britons expected relatives from Vancouver to meet ships of refugees in Halifax – to D-Day and the liberation of the death camp at Buchenwald.

Gerald Clark stayed on to cover the trials at Nuremberg.

One of the accused was Alfred Jodl, German Chief of Staff for war operations. He was convicted of war crimes and hanged on October 16, 1946, the court turning down his request for a more honourable military style firing squad. Admiral von Friedeburg, commander of German U-Boats in the north Atlantic, committed suicide on May 23, 1945.

In France Gerald Clark was jammed into a crowded courtroom to witness judges issue a death sentence for Marshall Petain, who ran the collaborationist Vichy regime. His sentence was commuted to life in prison, and he died in 1951.

The war made Gerald Clark’s reputation as a reporter and gave him a lifelong urge for action and covering foreign news.

After the war he returned to Montreal where he continued to work for the weekly Montreal Standard, a paper owned by the McConnell family who also ran the daily Montreal Star, where Mr. Clark soon worked. While Mr. Clark prospered as a journalist, his mother would have preferred that he become a doctor.

Polly Fink and Shmuel Klughaupt came to Canada in 1903 from Galicia at the eastern edge of Austro-Hungarian Empire. “You can’t come to a new country to Canada with a name like that,” said a Canadian official on their arrival. On their way they had worked in England, and he asked what they did there. The reply was clerk, said in the English way, so the name became Clark.

Jacob Clark was born in Montreal in 1918, but his sister soon called him Gerald and it stuck. He was later to say that his anglicised name helped him avoid some subtle anti-Semitism in Montreal. He was the first Jewish editor-in-chief of the McGill Daily, and he said Gerald Clark on the masthead didn’t raise any bigoted eyebrows.

McGill itself had a type of quota system for Jewish students. The standard for entry was 60% in the Quebec high school matriculation. However, for Jewish students it was 75%. Young Gerald saved for university canvassing door to door for a city directory and sweeping floors in his father’s small garment factory.

At McGill he studied science, because his mother thought that with careers such as banking closed to Jews, medicine was a place her son could prosper. When he told his mother that he wanted to become a journalist, she replied:

“You can be whatever you want, as long as you’re a doctor.”

After graduating from McGill, he applied for a job at the Montreal Star. The editor turned him down. He then landed at Canadian Press re-writing the `blacks’, the carbons of stories from the daily newspapers. He lasted one month. It was his luck that the Gil Purcell, the tyrant who ran CP, was in Montreal and caught him making two mistakes, one of them a football score.

It was a lucky break. Young Gerald Clark was taken on at the Montreal Standard and soon became a feature writer. When war broke out, he volunteered for the artillery. He did some training but flunked the military medical. He stayed on as a reporter.

Gerald Clark was the type of reporter every editor loves. Send him anywhere in the world and he would soon be filing back well-crafted stories from news bulletins to long detailed features. In the early 1950’s he moved from the Standard to Montreal Star, and by 1955 was back in London as the paper’s correspondent.

Mr. Clark travelled through the eastern bloc at the height of the Cold War. In his memoirs he records petty annoyances such as having his camera seized by Polish secret police. But in Hungary in 1956, he managed to work around the government-controlled censor.

Before leaving London, he set up an arrangement with the Daily Telegraph, where they had operators who took down copy over the phone. Mr. Clark made a deal that the Telegraph could use his copy as long they transmitted it to the Montreal Star.

At a time when American reporters were not allowed to cover Red China, as it was then known, Mr. Clark went there for his paper. He produced feature stories and magazine pieces and a documentary, Report from China, which aired first on CBS in the United States—where it won an Emmy—and then on the CBC.

The trip produced a book: Impatient Giant: Red China Today, the first of five books he published. He had travelled through China with a state guide and interpreter and got some things right and some things wrong. He astutely judged that China would become a major economic power. However, he claimed China’s steel production had passed France during the so-called Great Leap Forward. That attempt at back yard steel making and industrialization was a failure.

Back at the Montreal Star he was promoted to Associate Editor, then Editor in charge of the editorial page. He remained the Star’s main foreign correspondent and travelled around the world. In 1961 he went to Israel to cover the trail of Adolf Eichmann.

“The Eichmann trial left an impact on him as a Jew and how he saw the need for Israel,” said Stanley Cohen, a young writer at the Star who was Mr. Clark took under his wing.

There was some debate among his family and friends over just how many times he visited Israel; his wife said it was 50, one of his friends said 99. Once during the Six Day War, when the borders were closed, he flew in from Cyprus in the belly of military plane.

He interviewed every major Israeli leader, from Ben Gurion to Rabin.

“He reported on Israel with the great candor and undisguised admiration, but he left the cheer-leading to others,” said Ned Barrett another former colleague from the Star.

The man from the Montreal Star amazed his colleagues with his knack for landing interviews with the famous of the world from Che Guvera to Bob Hope. At home he took up national and local issues, such as medicare. He wrote such strong editorials in favour of health care that one doctor who railed at the system of socialised medicine refused to take Mr. Clark as a patient.

“He was a revered figure at the Star, regarded as a model by the younger journalists” said Peter Desbarats, former head of the Journalism School at the University of Western Ontario who started as a reporter at the Montreal Star. “He was a real gentlemen journalist. And incredibly modest. I never knew about all his accomplishments in the war.”

The Montreal Star closed in 1979 after a strike. Gerald Clark was devastated. He continued to write, in particular for Reader’s Digest which sent him around the world doing things such as features in Japan and a two-part series on South Africa in the dying days of Apartheid. Though he worked for magazines, he couldn’t shake newspapers out of his system.

“He retained the instincts of a daily newspaperman. He always wanted to be where the action was,” said Alex Farrell retired editor-in-chief of Reader’s Digest in Canada. “He made the adjustment to magazines, but it took him a while.”

One example was the Gulf War of 1991. Mr. Clark was in the Middle East and ready to file a story on Scud strikes in Israel, but the war ended so quickly the magazine, with its long deadlines, couldn’t use the piece.

Gerald Clark was active until the last day of his life. He played tennis at the Mount Royal Tennis Club until about 6 years ago when his eyes deteriorated. He then read and wrote on a computer screen with giant print. He bought the latest Apple model a few months ago.

Mr. Clark loved Montreal and wrote a passionate book about the city called Montreal the New Cite. He his wife Barbara and their Shih Tzu dogs lived in an apartment in Papineau House, a building in Old Montreal restored by the late Eric MacLean, another colleague from the Montreal Star.

Gerald Clark was born in Montreal on April 3, 1918. He died at home in his sleep on July 7, 2005. He is survived by his daughter Bette, who lives in New York City, and by his wife Barbara. He was a widower twice. His two other wives both died of cancer.