Tariff Worries, Lenin’s Comment on Syrian Regime Change and Canadian Politics

December 30, 2024 Volume 5 # 28

Trying to Beat the Trump Tariff Threat

Container ships are packed as companies try to get goods in under the January 20th Trump inaguration and the threat of tariffs on Chinese Goods.

“Transpacific rates climb,” says a weekly newsletter from Freightos. “Rates are up 15% and vessels are full as importers and exporters try to ship ahead of potential tariffs….Shippers should prepare for rate increases in January, especially on transpacific and transatlantic routes.”

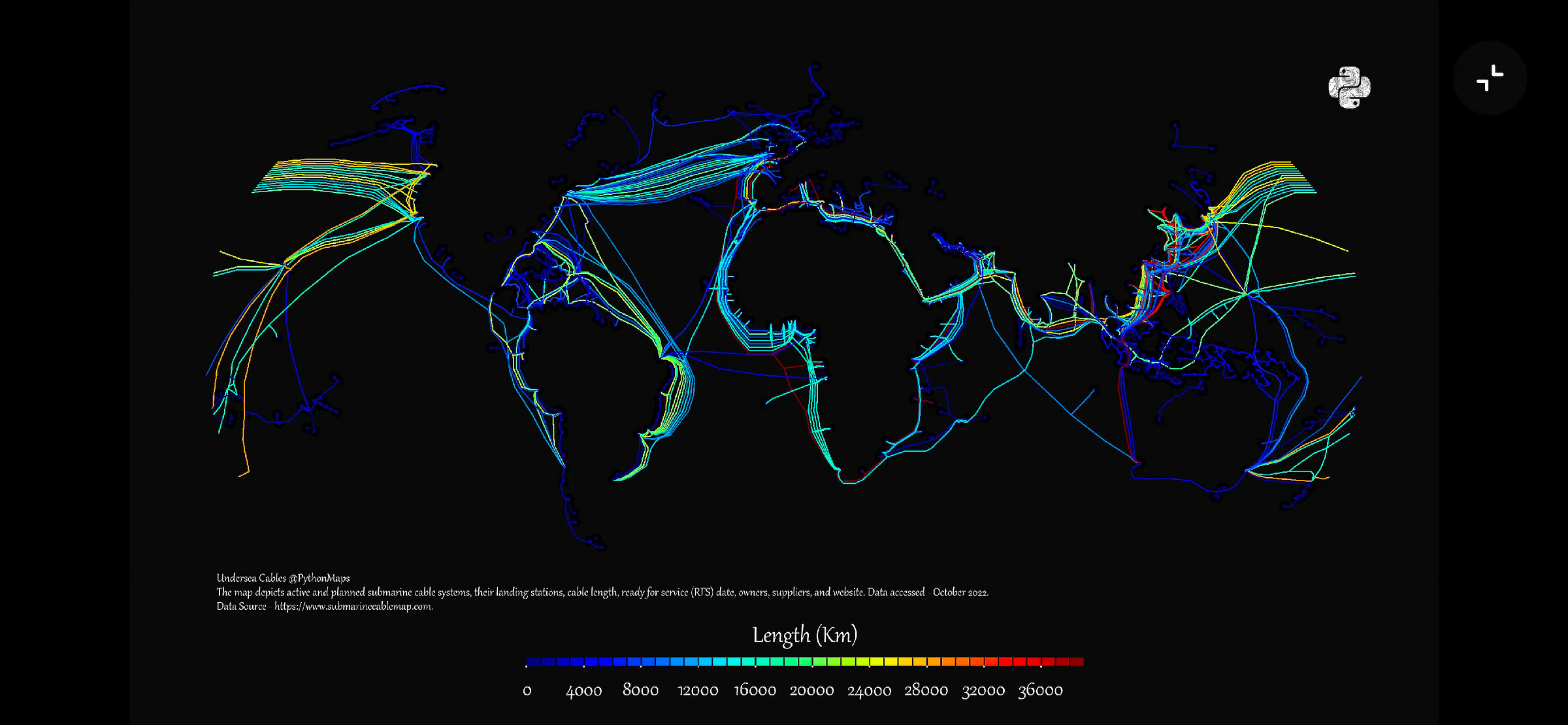

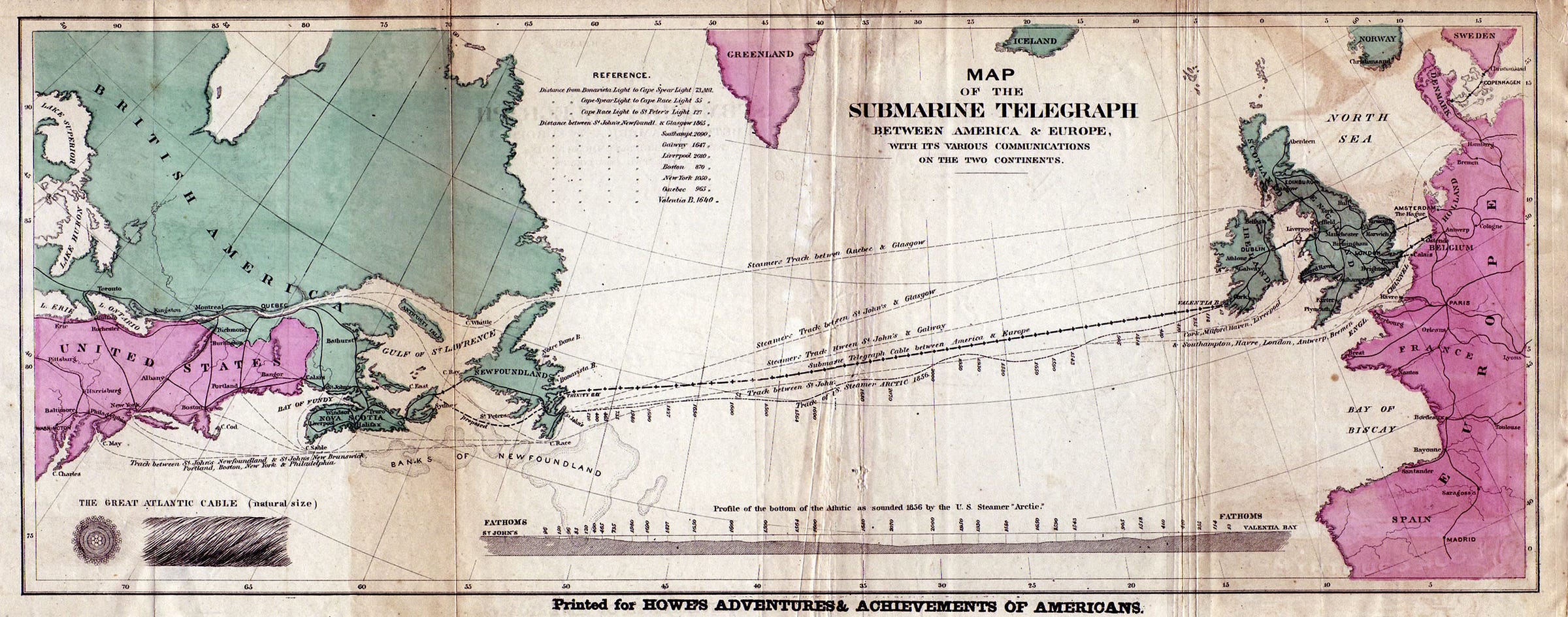

Undersea Cables Connect the World

The first transatlantic communications cable was laid 170 years ago. Telegraph. Nothing else had been invented by 1854. It went from Newfoundland at first.

.

Lenin Died 100 Years Ago; But He Could Have Said this Yesterday

The Assads are now in Moscow.

Out in a week in December after a takoeover no one saw coming. The British-born Asama al-Assad is said to want a divorce. I guess. Her siblings, all doctors, still live in Britain. She might not be allowed to return. She is also said to have leukemia. The British tabloids are giving her no sympathy.

****

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s demise came one week in December, knifed by his Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland (after he knifed her) who called his spending plans a political gimmick.

Marching along in happier days.

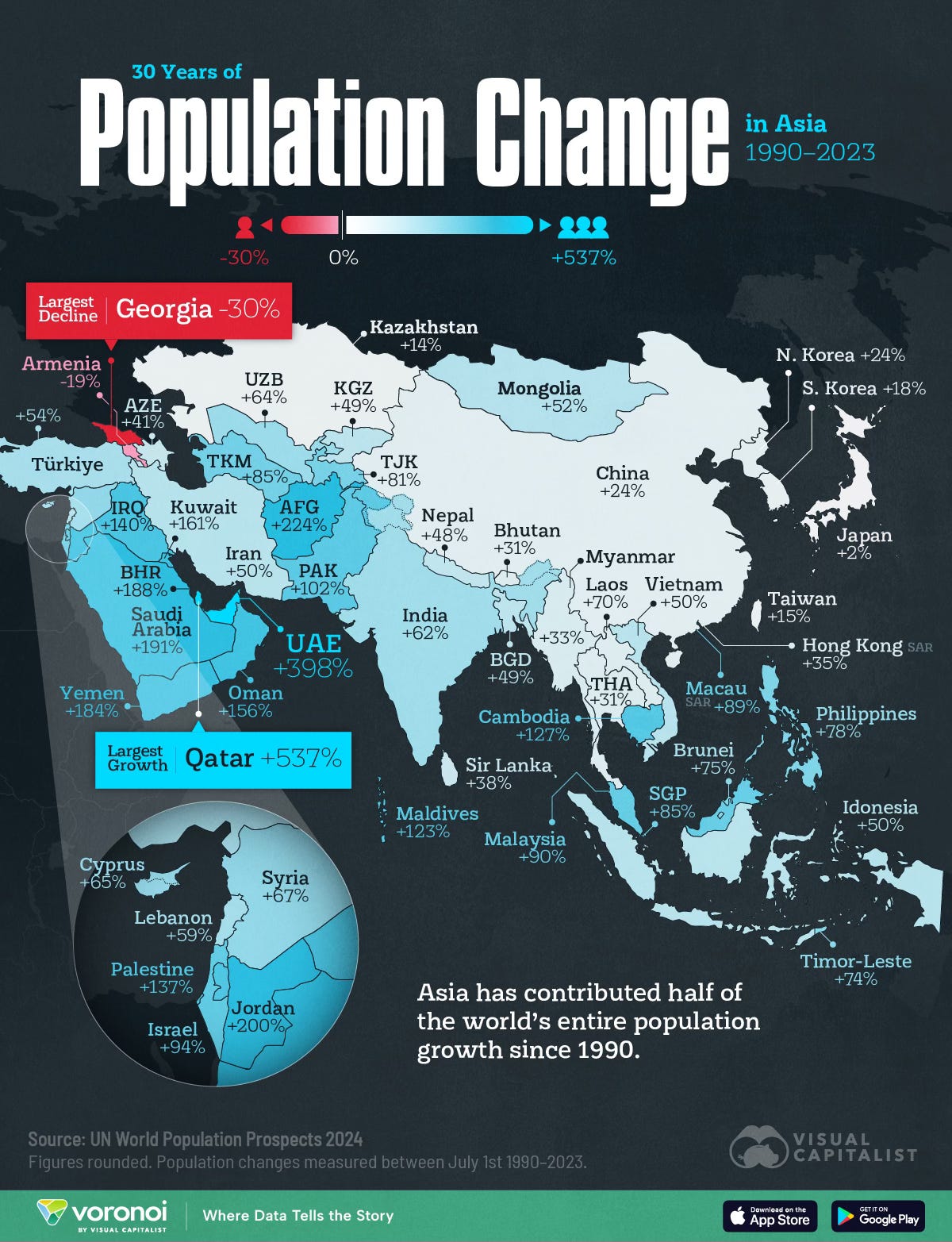

Demographics

Ups and Downs

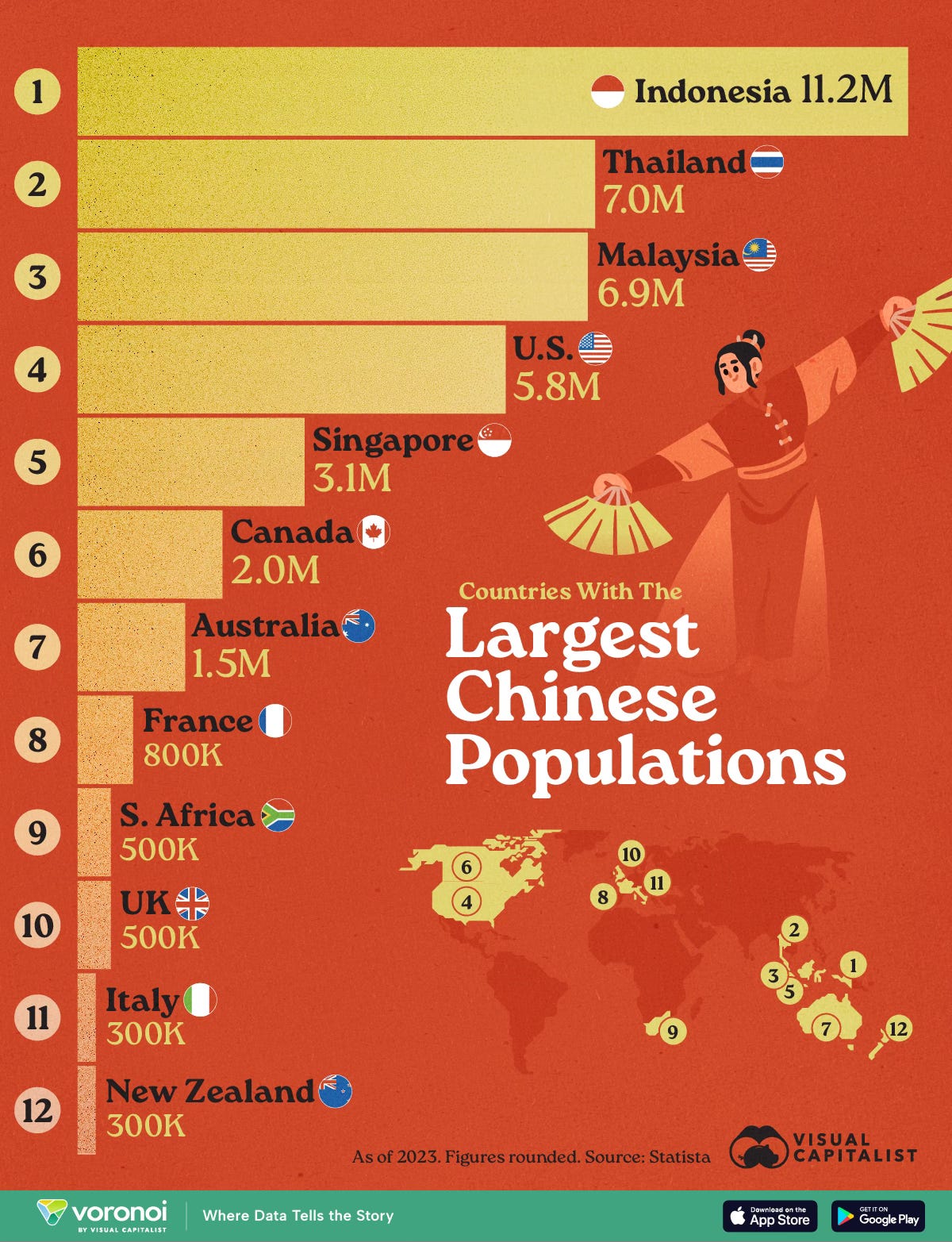

The Chinese Diaspora

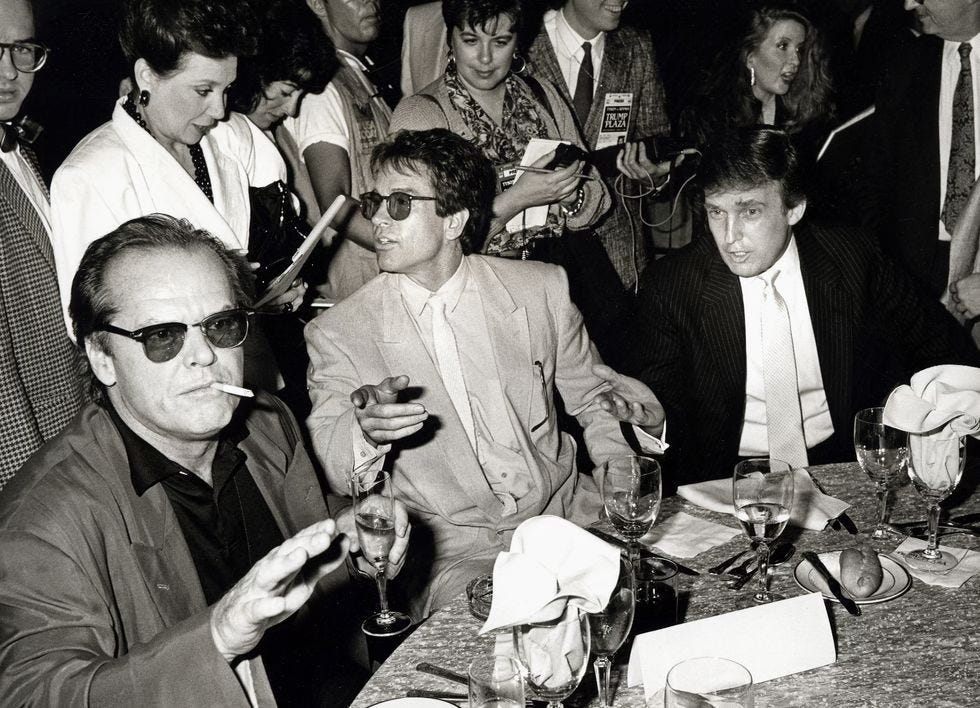

A Trio at Studio 54 (I think)

The Uber-Liberal Warren Beatty must be aghast looking at this old photo. But back then the Donald was a Democrat. Jack Nicholson was busy doing decadence.

An Old Car Article

Once upon a time I wrote car articles for the National Post. My agreement with the CBC, my main job, was that I couldn’t accept freebies like testing a Mercedes for a month. One of my tricks was sticking my business card on the windshield wiper of a car I thought was interesting. A 1969 Lamborghini or a 1972 Mercedes 300 SEL. I will run a few of them, those I can find. The National Post does not have older back issues digitized, so I have a few on my computer, but not many. This the file as I re-sold it to Wired Magazine, though they cut it down to size.

The Triposto

The prototype of the Triposto was named the most beautiful car in the world at the Montreal Auto Salon in 2000. It certainly is beautiful – and fast—but it is not the easiest car in the world to get into. The Triposto is a custom built super car put together by a father and son team in Montreal, Hugh Kwok and his father Clyde.

As the name Triposto suggests, this is a car with three `posts’ or three seats with the driver’s seat -- moulded to the owner’s body-- smack in the middle and a little forward of the two passenger seats.

“It’s not that hard once you get used to it,” says Hugh Kwok, who with his father Clyde Kwok, designed and built the car. He grabs a side of the seat and slips into the middle seat in a two quick moves. Trying it for the first time tests the flexibility of an aging body.

Once in place it is quite cozy, the steering wheel close up like a race car and the tachometer the only dial in front of you. The other information you need comes up on a digital display once the engine starts. From the outside you would swear this is a mid engine car, but it is not.

The Triposto is built around a stripped down Porsche 911 chassis. It is powered by a 3.6 litre engine from the 1993 911, one of the last air cooled models, the one that makes the wonderful Porsche noise that the newer water cooled Porsches are missing.

This is not a reproduction. The mechanical innards are all Porsche, the body is designed and built by the Kwoks. It is featherweight, just 1,000 kilograms, and has an estimated top speed of 280 kmh. This Triposto has been road tested on the track at Circuit Mont Tremblant. You can buy it to drive on the street for $250,000. The latest customer: a Montrealer who is taking the car on a move to California.

“We’re only building two to three cars a year. They’re hand built and we can’t build more. We like to keep the operation small so we can enjoy what we’re doing” says Kwok.

The Triposto is third car the Kwoks have designed. The first was called the Spexter, and it was their vision of what a Porsche Speedster would be in modern clothes. It has the low windscreen of the original Speedster, a Spartan interior but a moulded aerodynamic body in silver and a 2.7 litre Porsche 911 engine from 1982 in back.

The next car was the 928 Spyder, built on the frame of the Porsche 928 and using its front engine v-8. It looks a bit like a Porsche Boxster, but it was prodcued in 1993, three years before the mid-engine Boxster appeared on the market. The Kwoks have sold several for $125,000.

“I buy every 5-speed 928 I can find. It’s a very under rated car,” says Kwok. “Our 928 Spyder works even better than the original donor cars because of the improved aerodynamics and weight reduction.”

The Kwok family operates under the name Wingho Auto Classiques Inc. It is in fact two businesses: one designing and building one-off cars based on Porsche frames and engines. The other is restoring old sports cars, almost all of them Porches. Hugh Kwok specialises in restoring Porsche 356’s.

Not all the cars he looks after are Porsches. Hugh Kwok used to service the Mercedes 300 SL owned by Pierre Trudeau, and on the wall is a picture of the former Prime Minister in a 928 Spyder.

“I race the cars we build, and I also race a Porsche 356,” says Hugh, who among his other achievements was Canadian junior tennis champion in 1982. He is standing near a silver 356 SC, a 1964 model whose modified four cylinders would outrun most older stock 911s.

The Kwoks work in two places and we looked at the Triposto in a large six bay garage in downtown Montreal. Much of the restoration work is done at two airport hangers at Beloeil about 20 kilometres south on the other side of the river.

“I call this my laboratory,” says Dr. Kwok, in the garage where you don’t see any grease. It is as clean and tidy as most hotel rooms. Mirrors line the wall, making it seem larger, and there is a bar with an espresso machine.

Clyde Kowk is a retired engineering professor who was born in Shanghai and educated first in Hong Kong then McGill, where he got his doctorate in mechanical engineering.

“My speciality was fluid dynamics, and that made me appreciate aerodynamics,” says Dr. Kwok running his hand over the smooth shape of his 928 Spyder.

But like his son, the Triposto is now the love of Clyde Kwok’s life.

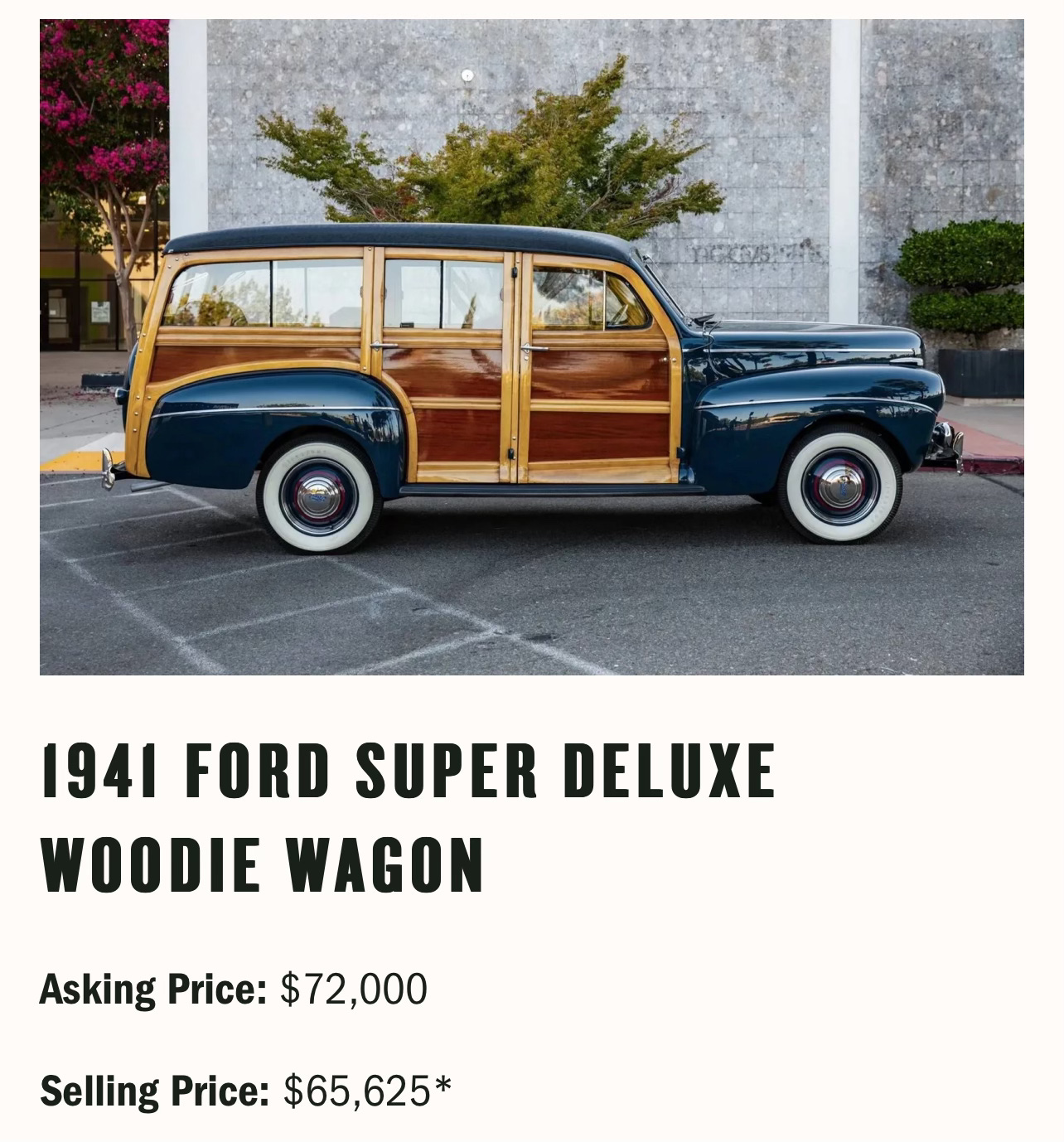

Just the thing for Shopping on Martha’s Vineyard

This from Hemmings Motor News this past week.

Essay of the Week

This is another chapter in the life of William (Bill) Marshall DFC, a book I co-wrote more than 20 years ago, By this stage of his life Bill has run away from home and signed on to a freighter called the Harmattan.

This is a longish read, but it’s that lazy period between Christmas and the New Year.

***

FLOTSAM AND JETSAM

Tramp steamer is a common enough phrase, but who knows what it means? One simple definition is plucked from the Oxford English Dictionary: A cargo vessel, esp. a steamship, which does not trade regularly between fixed ports, but takes cargoes wherever obtainable and for any port.

It’s a new sort of expression, tramp steamer, and first came into use in English about 1880. And the tramp part has nothing to do with easy women as in the song title, That’s Why the Lady is A Tramp. That’s an American expression. The steamer moved like a tramp, a vagabond who traveled the roads with no direction. The tramp steamer, like the tramp on the move, never knew its next destination or where it would get its next meal.

The tramp was at the low end of the shipping food chain. Its specialty was to trade in ports that had no cable connection back to England. That way the cargo had to be negotiated on the site, with the captain and the shipping agent making the deal. The only link to the home base was the wireless on board the ship, receiving messages in Morse Code.

Tramp steamers filled the niche in the shipping market that the big steamships could not. Many of them had just enough structural integrity and safety gear on board to squeak by the insurance inspector known as the Lloyd’s Surveyor.

In real life the tramp was a ship that sometimes waited weeks for a cargo, while its captain worried what to do with a restless crew. They could paint the ship, clean it or fiddle with the mechanics on board; but most of the time they yearned to get ashore to go on the piss and chase women.

Cargo ships like the Harmattan were the backbone of the British Empire. They took British goods to the world, but also produced the invisible profits that helped keep the City of London alive. The Baltic Exchange, Lloyd’s of London. None of them would exist without the risk takers who sent cargo ships on round the world tours.

None of this economic theory was known to young Bill Marshall. He was angry with his father and determined to show the world he was his own man. Somewhere along the way he was sure he’d meet up with a horse again, but not on board a ship of course.

All of a sudden life changed for Bill, from the harsh words of schoolmasters to the crude words of sailors. These were tough men, who laughed at the silly clothes the boy wore.

“They soon gave me some things to wear. It could be cold that time of year. Almost right away they started making fun of me, but I took a swing at one of them. I couldn’t do much but I wanted to show them I wasn’t a namby-pamby. They left me alone after that. But I can tell you, you learned your manners.”

That wasn’t all he learned. Bill was an untrained hand and the older sailors started teaching him things about ropes and lines. He had to learn the workings of the winches and how to open and close hatches, and how cargo was loaded on a ship. This took several months to learn, not just a few days.

“There was nothing to do but work when we were at sea, so you might as well learn.”

They traveled round the coast of the England, though pieces of water with storied names; The Solent, the Black Deep and The Wash, plain English names given to channels and estuaries by generations of British sailors and map makers. The Harmattan was bound for Newcastle, hoping to pick up the obvious, and bring the coal to Hamburg where they had a load of pig iron waiting.

As they passed through the seawall at South Shields and Tynemouth, he could see the big statue on the south side and one of the sailors told him when the North Sea was rough, it could come up and cover the top of it. Bill found it hard to believe, but it was true.

He remembered this was where he was born, South Shields. He hadn’t lived here long. His father had commanded a submarine in the First World War and was based here. That was August 14, 1918. Less than three months later the war would be over, and the Marshall family moved back to Chichester, where they belonged.

Bill’s father had been in the merchant service before the war, but as Captain of a passenger ship on the India Line. Port over, starboard home. The line liked their men to be in the Royal Navy Reserve, so when war broke out Cyril Marshall went straight into the service.

Submarines were primitive things back then. In the final months of the war his sub was depth charged and Bill’s father almost choked to death on the fumes from the batteries inside the sub. He retired to Chichester.

For the captain of the Harmattan the trip to Newcastle was a disappointment. They sat at anchor for two weeks waiting for a cargo of coal to take to Hamburg. Then he gave up, and sailed for Germany.

Life on aboard the Harmattan was work and sleep, work and sleep. The watch or shift was four hours long, followed by four hours of sleep. Round the clock, seven days a week when the ship was at sea, or loading cargo in a port. Bed for Bill and the other hands was a bunk, an iron bed with a straw mattress.

“The mattress was fine in northern climates, but once it got warm the bed came alive with bloody bugs and cockroaches,” laughed Bill years later, doing an imitation of how he’d be itching himself. “You didn’t get much sleep and you worked bloody hard. You might have a cup of coffee after a watch and then manage a couple of hours sleep before you were back at it again.”

There were 33 men on board the Harmattan, the skipper at the top of the pyramid, a man whose word was law at sea. There were 8 stokers, 4 for each watch, a chief engineer, whose job was to run the engines (and he had two deputies), a mate, second in command to the captain, followed by a second officer and a third officer.

The Bosun was a kind of non-commissioned officer who ran the deck crew, the 12 seaman, able and ordinary, of which Bill Marshall was one of the latter. There was also a man with the rather quaint title of Lamp Trimmer. Since there not lamps to trim on a vessel with electric lights, busied himself looking after stores and ropes and seeing to things such as the hatches and the winches.

Officers and engineers each had their own cabins. The seaman had bunks in fo’csle, in the front of the ship, while stokers lived aft with the engines and the coal.

At first Bill Marshall thought he had signed on to hell. The sailors seemed gruff men; some of them grunted at him. Most of them had started at the bottom and they knew what he had to learn before he was any use. But they were kinder than the older boys at Rugby would have been; at least they got him into some warm clothes.

The captain was known to the crew as Skipper, and it was a phrase Bill Marshall used all his life. Whether it was a friend or a waiter, if he liked a man he called him Skipper. The captain was tough, he had to be to keep this crew in line, but he had a broad honest smile and every human weakness, in particular booze and women.

Hamburg was the kind of place the skipper loved. Beautiful women and lots of them. The only problem was they were expensive and so was docking in Hamburg. They would only be there a few days while they picked up the cargo of pig iron for the West Indies and Buenos Aires.

An old sailor named Ken took Bill ashore in Hamburg. Old was anything over thirty five to someone that age. Ken was an able seaman, just one notch up from Bill, and he dished out the kind of advice a master at Rugby would never had done, advice a master at Rugby might not have even known.

“Stick with me, my boy. The rest of them will all rush out and get pissed, then go to a whorehouse. That’s backwards. You’ll enjoy it a lot more if you go to the whorehosue first, when you’re sober, and then go on the piss later.”

Sound advice. The two of them went a cheap brothel in the port and Bill got laid for the second time in his short life. He and Ken then got pissed and rolled back to the ship. The next day he noticed Ken sweating and breathing heavy as they worked loading the pig iron into the hold. At 14 a hangover is gone about five minutes after breakfast.

The Atlantic crossing was hard work, a non-ending string of four hour watches. The only way to forget work was to get better at it. The older seamen taught Bill the workings of the winch, not just how to work it but how to repair it in a hurry. In port winches were used for loading and unloading cargo and it cost money to have them out of service.

The Harmattan was going slow, maybe 7 knots, with her belly filled with pig iron. She would slow even more in a heavy sea. Bill didn’t envy the stokers, and he knew the engineers did their work, but he did begrudge one man his station in life: Sparks, the wireless operator.

“The easiest job on the boat by far. All he had to do was sit by the wireless and wait for messages. He had to know Morse Code of course. And every ship of a certain size had to have a wireless operator and he had to be on duty. Lloyd’s rules. So he sat there, or lay there and tapped out the occasional message or jotted down the ones he received. Most of them were drunks. Little wonder, there wasn’t much else to do.”

About a third of the way across the Atlantic they picked up the Gulf Stream and the weather that warmed the ship and brought the bed lice and cockroaches out of hibernation. Still, it was better than miserable drizzle of the North Sea and the North Atlantic.

The sea trip from Hamburg to Buenos Aires is about 6,400 miles. There was no way the Harmattan would make that without a stop. They needed fuel and food. Bill recalled the food could be grim. In port the steward and cook stocked up on supplies. But there was no refrigeration so fresh fruit and meat ran out about ten days out of port.

After the fresh stuff ran out it was diet of salted port and beef, stored in barrels, along with hard-tack, the biscuits of the seas. The never ending taste of salt along with a daily dose of lime juice to fight scurvy.

The ship, of course, ran on coal, and it had to be re-stocked with coal and water for the boilers, same as a steam engine for a train. Bunkering was the word for it and it wasn’t like filling up a tank with petrol or diesel. It was done at a special depots and by people who knew what they were doing. Coal dust was dangerous, as likely to burst into flame as petrol.

The coal came down chutes, and men called trimmers made sure the load was even in the coal hold. It would take five or six hours to bunker a ship. If they were going to take a long trip, as this one would be, they stored extra coal under wraps on the aft deck. There would be anywhere from 20 to 40 tons of coal on board.

Bunkering was a filthy business.

“Everything was covered in coal dust, and it was our job to get it all clean,” remembered Bill. He laughed at the suggested image of sailors mopping the decks. “There were no mops. You washed the ship down with your bare hands using old rags and something called Soogie, which was a mixture of soda and water. There were no gloves and it was dammed hard on you. Afterwards we’d rinse the ship off with sea water.”

Cuba was the place they chose to stock up on coal. Part of the shipment of pig iron would be dropped off there and they’d pick up some sugar for the restaurants of Rio or the cafes of Buenos Aries.

The Harmattan sailed south from Santiago, keeping to the Caribbean side of the islands that formed a barrier, the idea being to sail behind them to block out the worst of the Atlantic. They came out at Trinidad, heading for their first port just past the nose of South America. Rio de Janeiro. The trip from Cuba took even longer than the Atlantic crossing and they were anxious to get ashore to the bars and brothels of Rio.

A great place Rio, but Argentina offered more potential cargo—it was so much richer—and so they only stayed there for a couple of days to unload. A few days after they left Rio they were all glad to sight civilisation once more as they rounded the tip of Uruguay into the giant estuary of the River Plate, Rio de la Plata. It was past midnight, but the lights of Montevideo were still bright. But off to the south and west half the sky seemed to glow from the aura of what was then the biggest city in South America.

Bill was out on the deck long before they moored at Buenos Aires, which seemed to him a city as big as London, and more beautiful. The men would be disappointed though, for there would be just a day ashore in the metropolis of South America, a place where people were so rich they sent their laundry to Paris.

Sparks had picked up a message that they were to head inland as soon as they could. Another gift of the tramp steamer was that most of these freighters could navigate deep rivers, and head to places most ocean going vessels could never reach. They were going to Rosario, about two hundred miles up the river.