Tech History, Revenge, A plan for an Invasion of Canada and another Chapter in the life of Bill Marshall DFC.

January 13, 2025 Volume 5 # 30

Long Distance In the Not too Distant Past

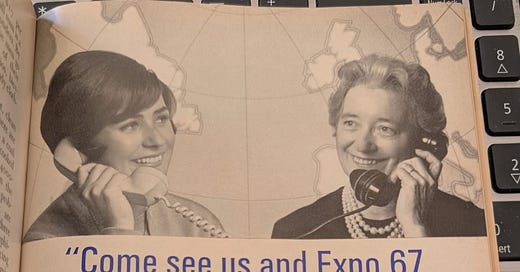

This is an ad from an old Reader’s Digest promoting a call home from Canada if you happened to visit Expo 67 in Montreal.

That $9 three minute call to Europe is $80 in today’s money. Today you can do it for nothing as services such as WhatsApp.

Then there was computing power.

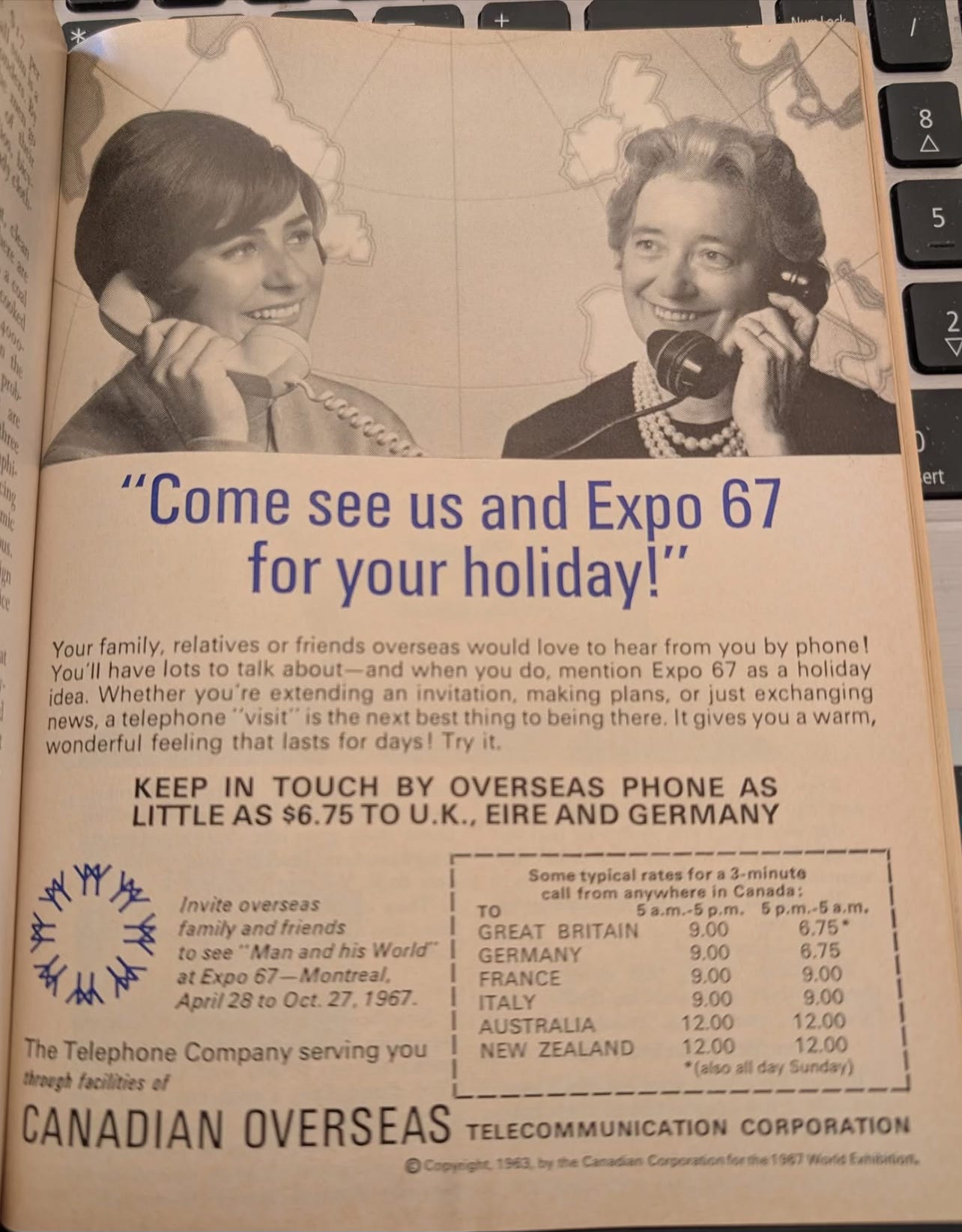

This picture is from 1966. Those 62,500 punch cards held 5 megabytes of data and took four days to load.

This memory stick holds 32 gigabytes of data— 32,678 larger than the pile of cards above— and it costs $30

.

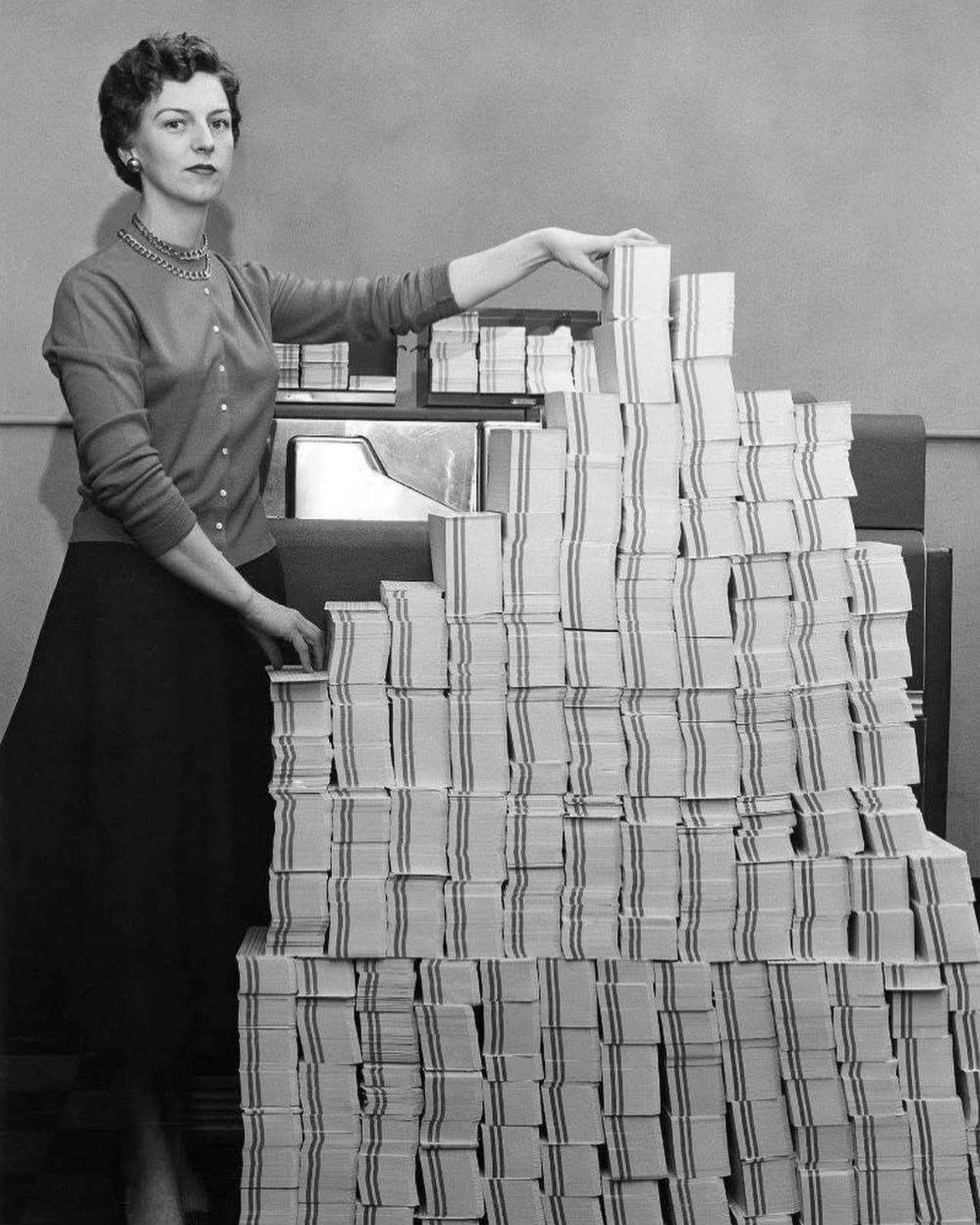

Revenge, a Meal Best Served Cold

My friend Leah Eichler, with whom I worked at Reuters in Toronto in the 1990s, publishes a SubStack, an interestuing read but she seldom writes on politics.

Leah ran a short item about her dealings with Chrystia Freeland, the former Canadian Finance Minister who brought down Justin Trudeau. Freeland is almost certainly running for Trudeau’s job. Here’s Leah’s note.

The 51st State?

Here is a story I wrote for the Daily Telegraph in April of 1991. The original is on a hard drive that has long since fused into one piece of metal, but here is a clip of page that is part of a collage of my old newspaper stories.

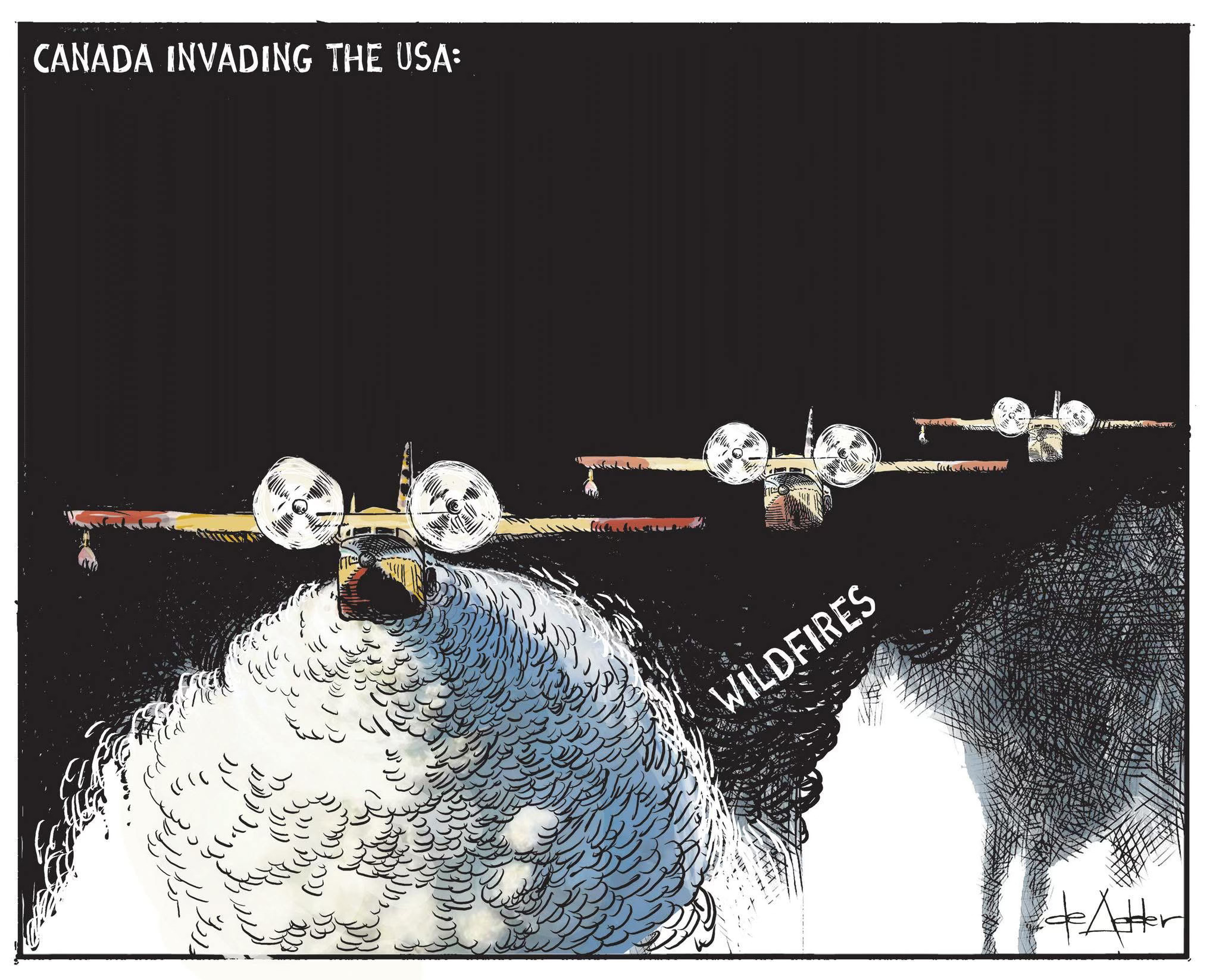

It didn’t mean the US was planning to invade Canada, just that there were contingency plans for even the most unlikely events. Let’s hope Trump doesn't see this. And speaking of invasions, here’s a clever cartoon by Michael de Adder.

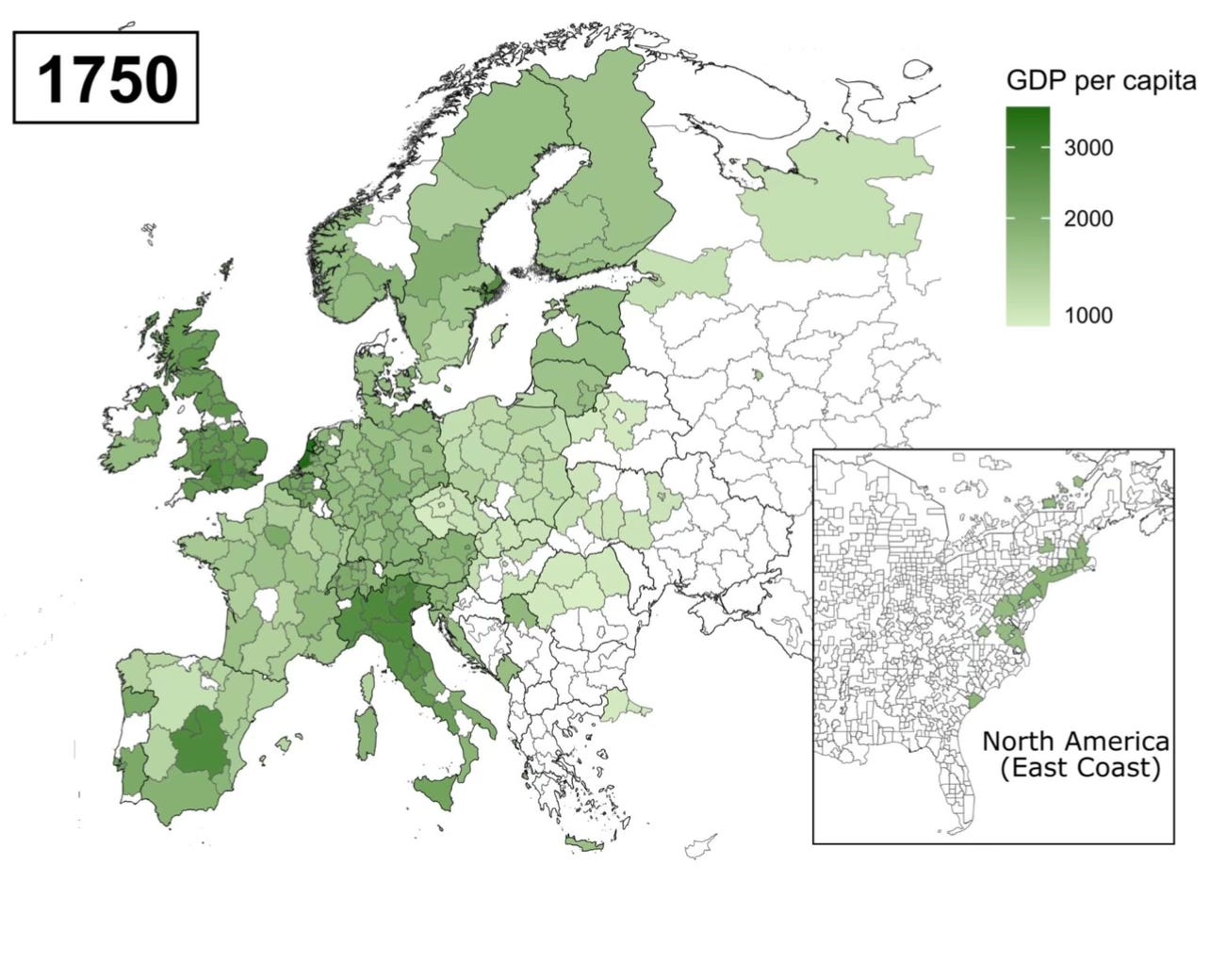

Which Countries were Rich

In 1750 you can see the rich places in Europe and colonial America, including New England and New France. England was rich, and so was the Netherlands. They had invented capitalism. Northern Italy was hugely rich. They invented banking and double entry book-keeping. Spendthrift Spain was already going downhill.

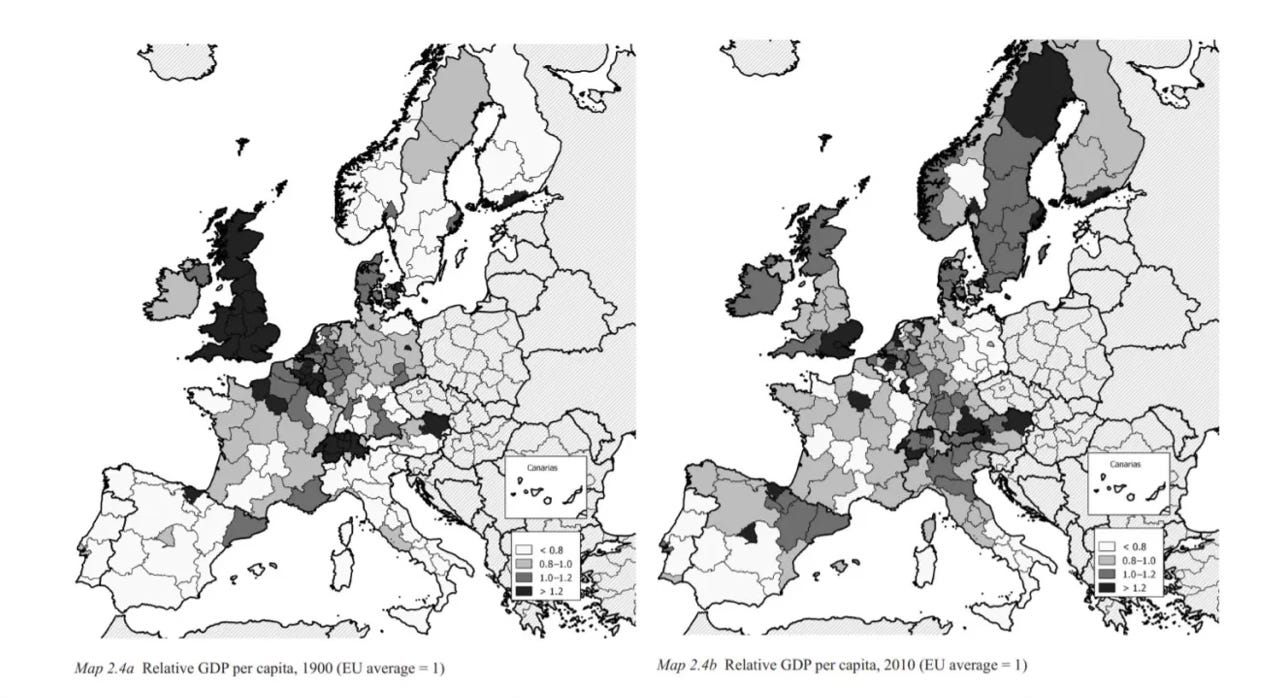

And then by 1900 on the left, and 2010 on the right.

Britain, lost out as number one. Two World Wars didn’t help. Ireland did well going out on its own. Northern Italy had lost its wealth, but made a comeback by 2010.

A Year in The Life

Essay of the Week

We are going to skip ahead in Bill Marshall’s life. It is the mid 1930s. His ship, the Harmattan, has left Argentina, gone to South Africa, back up the western coast of Africa and into the Mediterranean. As a reminder this is another chapter of the life of Bill Marshall DFC, a book I wrote at least 20 years ago.

By the time they left South Africa, Bill had been away for almost a year. So much for the six week voyage to Australia. And it was still a long way off. After Cape Town and Durban they sailed up the west coast of Africa stopping along the way before ending up in Aden.

From there it was through the Suez Canal.

Bill took out his map. “We’re halfway home,” he thought at the time as they doubled back into the Mediterranean. Later the skipper showed him where they were headed. The Adriatic and the port at Dubrovnik.

The Lucky Country

Bill Marshall wasn’t there when most schoolboys learn about the Ides of March. Instead of studying Shakespeare he was touring the world. But on the Ides of March in 1936 Bill Marshall jumped ship in Sydney Harbour. He had been away from home for a year and half and was not yet 16 years old.

He slipped away just before dawn, with all his possessions stuffed in a cheap case. Some work clothes, his six silk shirts he had made in Hong Kong and his one and only suit. There were no clothes left of his boyhood; the grey flannels and blue pullover had long worn out and been thrown overboard.

The first thing to do was to get away from the ship. The skipper was a good man, but he wouldn’t be too happy at losing a trained hand, which was what young Bill Marshall had become. The warm weather of the late Australian summer had seduced him and he’d been dreaming of land and horses grazing in green, open fields.

“There wasn’t much to it. You just got off the boat. Australia was still pretty much a colony back then, so if you had a British passport, that’s all you needed,” Bill told a friend years later. “There would be all kinds of immigration rubbish today, but back then there were no rules. You just walked in.”

Jumping on a tram and riding it to the end of the line was the quickest way to get away from the harbour. His mates from the ship would search the bars and doss houses near the port, but would give up when they didn’t find him in less than a day. Sydney wasn’t that big a city back then, about million, including the suburbs, compared to four million today. But it was still a big enough place in which to lose yourself.

Australia, like the rest of the world, was in a slump, the same economic hard times hitting England and America. Bill didn’t know that when he jumped ship, he left behind the only real job he’d have for a couple of years. In his pocket, a little more than 50pds, what he had left after spending on food drink and women in the ports on both sides of three oceans and three seas. For him, it had been six, not seven seas.

The first night in Australia was spent in a fifteen-shilling hotel. Comfortable with a good bath and a generous breakfast, but simple math told him if he stayed there it wouldn’t be long until he was broke. The next day he found a five-shilling boarding house and started looking for work. There was none, work that is, in particular for a young deckhand.

He’d decided he wanted to stay Australia. “The people were friendly. People talked to you and it seemed to me everyone had a smile on their face. And there was a pub on every corner. The only trouble was that terrible slump. There were no jobs.”

After a month or so in Sydney, young Bill was broke and hungry for the first time in his life. He went back to the docks locking for work there, maybe unloading ships. The idea of being a seaman again had no appeal. Knowing the old hands on the Harmattan had shown him there was no future at sea, even if you made it to skipper, which he reckoned he could.

Bill was out of money and slept rough in parks for a few nights. The Sydney weather didn't make that too much of a hardship, but it depressed him. So he decided on a bold plan to find work.

He found a shower room at the main train station and cleaned up. Then he pulled his Hong Kong suit, tie and one of his silk shirts from his case and made himself the picture of the bourgeois schoolboy he once was. He headed straight for what he thought was the most expensive restaurant in town.

“I had a slap up meal. Prawn cocktail, steak and a half bottle of red wine. Then came the time to pay. I told my waiter I had better speak to the headwaiter. He came over and said `I hope there nothing wrong with the meal sir?’ I said the only problem is I can’t pay for it.”

Bill offered to do the washing up, to do any kind of job to pay for his food. He reckoned he could charm his way into a job once he stayed around for a few hours or however long he had to work to pay this off. But the plan wasn’t working.

“The headwaiter was pretty worked up. I guess they’d learned to watch out for this sort of thing, but my Hong Kong clothes fooled them when I walked in. I thought they might call the police. Then I got lucky. There was a man at another table, a prosperous, middle aged businessman and he came over and said `I’ll pay his bill.’”

That man was Peter Johnson, a punter who liked to gamble and a man who owned 5 horses. Inside of half an hour, Bill told him he knew a lot about horses, and how he’d gone to sea after winning a few steeplechase races. Within half an hour Mr Johnson had written a note to his trainer asking him to let Bill Marshall take a run as a jockey. He asked Bill if he wanted a ride to the racetrack. Bill had learned a long time ago it was better to look tough and independent. He’d walk.

It was 17 miles to the racetrack outside Sydney, the same distance it was from Chichester to Portsmouth except that was by bike. The Marshall charm did not work on the trainer, a rough kind of man named Bill Hudson. Like many Australians he didn’t much like Poms, and he loathed the looks of the skinny, scrubbed schoolboy in a dusty suit standing in front of him.

Bill Marshall weighed nine stone two, about 132 pounds. He would weigh about the same for the next 70 years. Hudson walked away as the boy pestered him, and in the end dragged the letter from his pocket.

Hudson looked at it, and knew he didn’t have much of a choice. The only way to get rid of the boy was to put him on a horse that would throw him off. “Well. The boss fancies your chances does he? Well let’s see m’boy.” Hudson pointed to a horse in a stall a few yards away, a chestnut with a white blaze. “Saddle that one up and let’s run some hurdles.”

It was almost two years since Bill had seen a horse up this close. But he was as determined as the day he first took a swing at the sailor on the Harmattan. He didn’t much like Hudson either, but he’d be damned if he’d give up now. For one thing he was hungry after his long walk from Sydney.

The young man stripped off his jacket and Hudson stared at the tattoos on his arms as he rolled up the sleeves on his silk shirt. He strode over, saddled the horse and mounted it as if he’d done the same thing an hour before. The test was over in ten minutes. Hudson led him to a practice track and Bill got lucky, making it over three hurdles without a hitch.

“Right. If we can’t get anybody else, you’re riding in your first race tomorrow.” Hudson turned and walked away, leaving Bill wondering what to do next. He guessed he’d better practice.

The first day of his racing career did not start well. He had no boots, no britches and only an old work shirt he’d worn at the track. He’d made friends with a couple of jockeys and one of them lent him a pair of boots, another gave him some worn out britches.

Steeple chasing at this course was run over two miles and over nine jumps. The track was a one mile oval with four hurdles so they’d have to run it twice. That made eight hurdles, The ninth came just at the end of the straight run in that led into the oval. That was the starting post.

Each of the hurdles were three foot six and covered in shrubs to give them the illusion of a country hedgerow, an English country hedgerow since there weren’t any real hedgerows in dry Australia, outside the richer gardens of Sydney or Melbourne.

It was an amateur race and that meant the jockey could bet on himself. Bill Hudson had given his new rider the money to make the wager, though he didn’t hold out much hope. It surprised him that after the first mile and one furlong; young Bill Marshall was running third in a field of sixteen. Three riders were already off their horses.

As they raced down the stretch before the final hurdle and the fence line, the chestnut horse with the Pom on board was running neck and neck with a grey gelding. At the last green fence the gelding hesitated, the bay went straight over and Bill Marshall won his first race in Australia. Bill Hudson collected 15 to 1.

“I started to ride for him. Rode a couple of winners and bought myself an old caravan to sleep in. I didn’t have to shave much in those days, so I’d just wash up in the stables,” laughed Marshall. “I even started to pick up some other rides, and soon enough I had enough money to buy a few horses of my own. Not bad for a fellow who was sleeping rough in a park three months earlier.”

He paid 50 pounds for his first horse, a 4 year old bay stallion. The first thing Bill did was have him gelded and that calmed him down. The vet bill was worth it. The horse won eight races, not every one he ran, but enough to but two more horses. He had his own travelling racing stable.

The race season was coming to an end and Bill had decided to learn the life of the itinerant trainer, jockey and owner. He saddled up one horse, put the two other on a lead and headed north. The Australian version of the Sporting News told him where the next country race meeting was and he headed there to see what he could win.

About this time he picked up one more asset and his first employee. He bought a horsebox, a lorry that doubled as a portable stall, stable and shelter if it ever did happen to rain in the dessert they lived in. He paid an aborigine to drive the horsebox and help him take care of the horses.

“Once you were away from Sydney,” said Bill, “Australia was a different country. Not many fences and the farms spread out. But every town had its race meeting and it seemed to me it was biggest social event of the year. They loved to gamble and there were lots of little race tracks.”

Most of the time Bill and the three horses would arrive two to three weeks before a race, though sometimes it might be as little as a few days. They would settle the horses in, feed them from their time on the road and then train them. Bill reckoned he could make 20 to 30 miles day when he was moving from track to track. The long walk down the dirt roads of the Australian countryside didn’t do the horses any harm and in fact kept them fit.

The sporting newspapers called these events, Country Meetings, giving them an air of respectability. The owners, trainers and riders called them Bush Racing. The tracks weren’t illegal, but they weren’t licensed either. There were few rules and regulations and a jockey soon learned to ride with Bush Rules.

There were stewards, so no one did anything blatant. None of the local farmers organizing the races wanted to be fleeced in a fixed race. For Bill it was as rough a life as living on the tramp steamer, except the language was a lot saltier in the Australian countryside.

“Every second word was fuck. You fucking pommie. You’re just a fucking pommie. When someone said you fucking bastard, it could either be the start of a fight or a saying hello to your best friend. It depended on where it was said and how it was said.”

Not that he hadn’t heard that kind of talk before but Bill Marshall picked it up and in his early adult life salted his language with the swear words he’d grown used to in Australia.

Following Bush Racing meant always moving north, moving up towards the Tropic of Capricorn that sliced through the top half of Australia. It took a while, almost a year until Bill and his aborigine companion made it to northern Queensland. He fished there for a while, catching the same sort of thing he would in Barbados more than fifty years later: barracuda, kingfish and dolphin, the fish not the mammal.

The farthest north he got was about halfway up coast that was framed by the Great Barrier Reef. He was now well into the Tropics and had doubled back when he ran his last race in Australia. Somewhere west of Brisbane, a man offered Bill Marshall a job.

Cattle herding.

The idea was take a herd of cattle, 800 beasts, and herd them slowly across half a continent to Darwin in Northern Australia.

“By this time I had about 8 horses, but the racing was little thin. So I signed on. It took us about six months. It wasn’t like the cattle drives in the movies. You walked them, watched them graze, taking your time. You wanted them to arrive fat not lean.”

There wasn’t much to a cattle drive. Just ride the horse behind and beside the cattle—and Bill’s horses—and sleep rough at night. The reward lay at the other end, a paycheque of 600 pounds. Along they way cattle would break their legs and one of the drovers would kill it, striking it between the eyes with one blow from an axe. In minutes the drovers would have it slaughtered. They reckoned, an Australian kind of word, that they only lost about five per cent of the animals on the trail.

Darwin was a disappointment. Bill had never seen such a desolate place. They delivered their cattle to the slaughter and then all went out got pissed.

“We drank them out of beer. Then we started on something called Red Bitty, which was awful Australian red wine. I have never been so pissed.”

Or so stupid. That night Bill played Two Up, a form a of heads or tails, where two coins are tossed on a blanket and the punter yells heads or tails. Bill lost six months wages in a couple of hours and fell asleep on the beach.

“I remember feeling awful and hearing a dog bark. It kept bloody well barking and I woke up. There about fifteen yards from me was the first alligator I had ever seen in my life. I almost shit myself,” and Bill was up and away from in a flash from what was a crocodile, not an aligator.. “Found out later it could have out run me, but they were full of food, eating all the offal in the river from the slaughter of the cattle. But I didn’t know that.”

At the northern tip of Australia, out of money except for his horses, Bill had had enough of Australia. Time to move on to another continent.

Africa.