The Italian Riviera, Colombia and Tariffs, Odd Maps, Sonny Corleone's Car and an Italian Immigrant's Story.

April 7, 2025 Volume 6 # 1

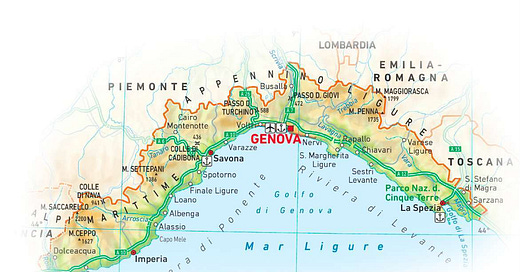

The land Once Ruled by the Doge of Genoa

The map above is just a strip of land known as Liguria, or the Italian Riviera. The original Republic of Genoa, which lasted from 1099 until 1797, when Napoleon shut it down, was much larger and its holdings spread across the Mediterranean and beyond.

This is the `Lungo Mare’ in the town of Camogli, 22 minutes by train from Genoa, but still part of Metropolitan Genoa, as is the nearby posh town of Portofino. The picture was taken at 2pm on Saturday, as the Italians flocked to the beach. People come from as far away as Milan for the weekend or the afternoon. It is empty during the week.

The temperature on the sign of a pharmacy in Camogli. The scene below was on a quiet day midweek, when I tried practicing my Italian reading the newspaper. The odd word, sfida, means challenge.

The headline came two days before Trump tariffs rocked world markets. I assume that anyone reading this already has calcuated their stock market losses, I have, and all but the most die hard Trump supporter is shocked at the carnage and the disruption to the rule of law in the United States.

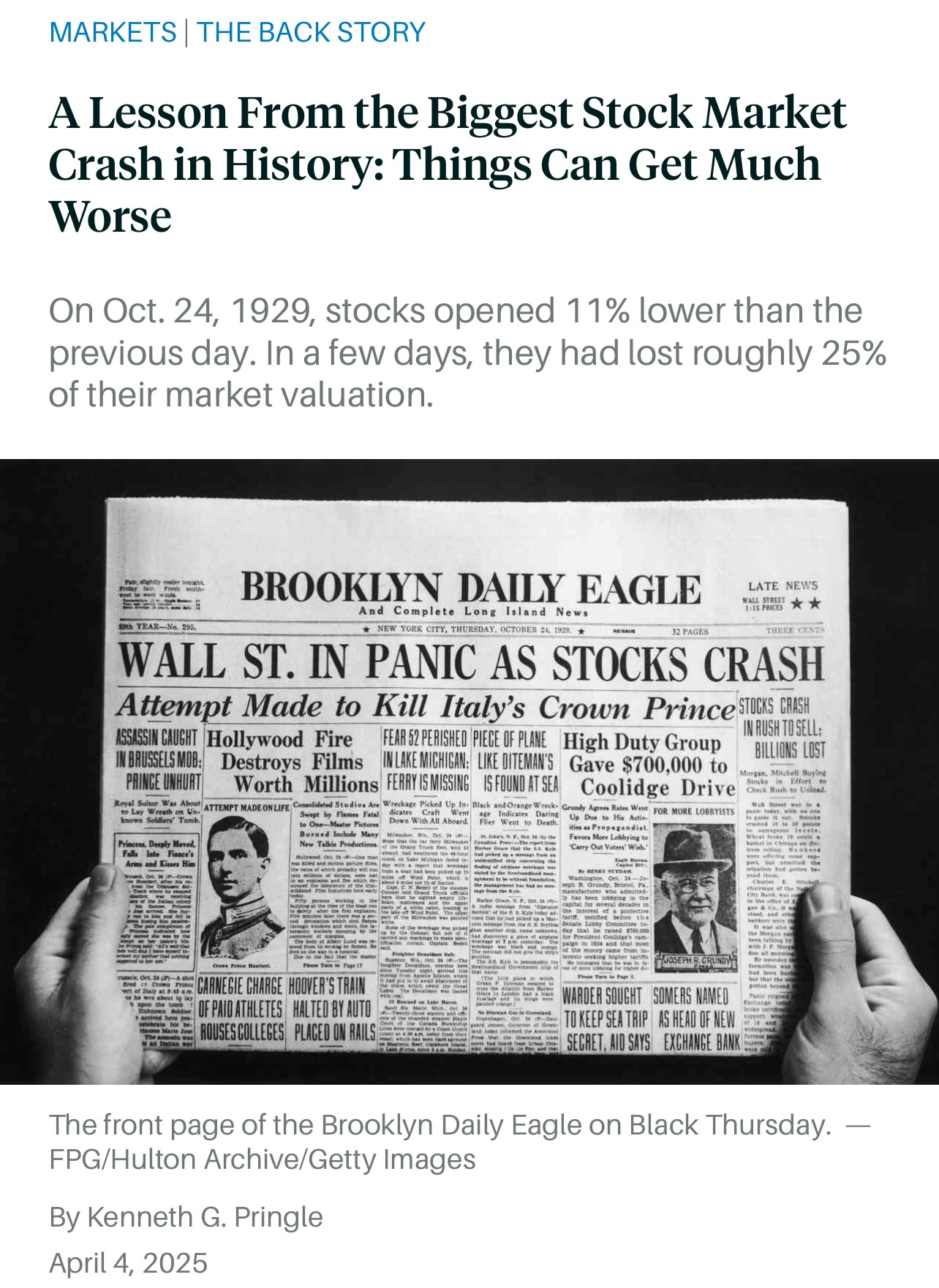

Barron’s Scares its Readers

And scares me.

Notice the 1929 headline“High Duty Group” talking about the wonders of tariffs. Rien change.

And it isn’t Just Stock Markets

Oil dropped 10% this week with WTI, the North American price, at $61.99.

Oil Price.com puts it down to Trump tariffs. “An oil price crash for the history books.”

Colombia Picks Saab over Lockheed

On Thursday of this week, one day after Donald Trump imposed 10% tariffs on Colombia, the country’s left wing president, Gustave Petro, said it will be buying Sweden’s Saab JAS 38 Gripen fighter, over the American F-16 by Lockheed.

Coffee Prices Bound to Rise at US Coffee Shops.

Brazil and Colombia are the two top suppliers of coffee to the United States which is the largest buyer of coffee in the world. And Colombia and Brazil produce the higher priced coffee, the stuff needed to make fancy things like Lattes and Americanos. Coffee prices were already at record highs. Chart from Daily Coffee News.

“At the time of this writing, the near-futures coffee prices on the ICE exchange (a.k.a. the “C price”) was sitting at an all-time high of around US$4.03 per pound.” Daily Coffee.

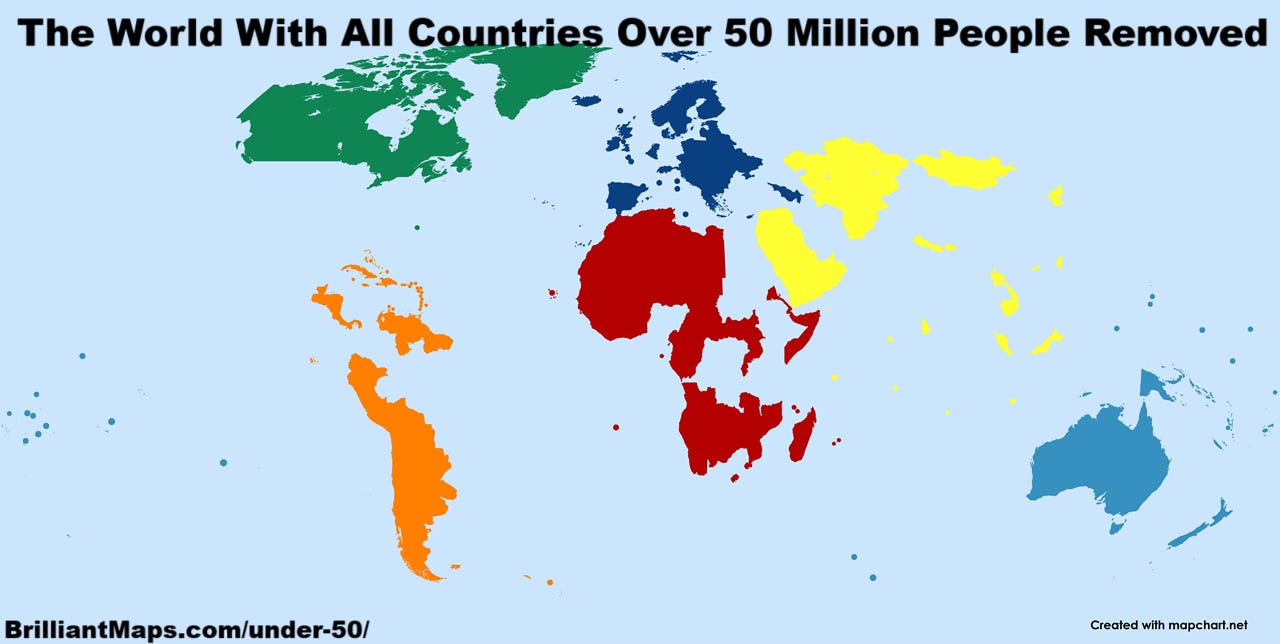

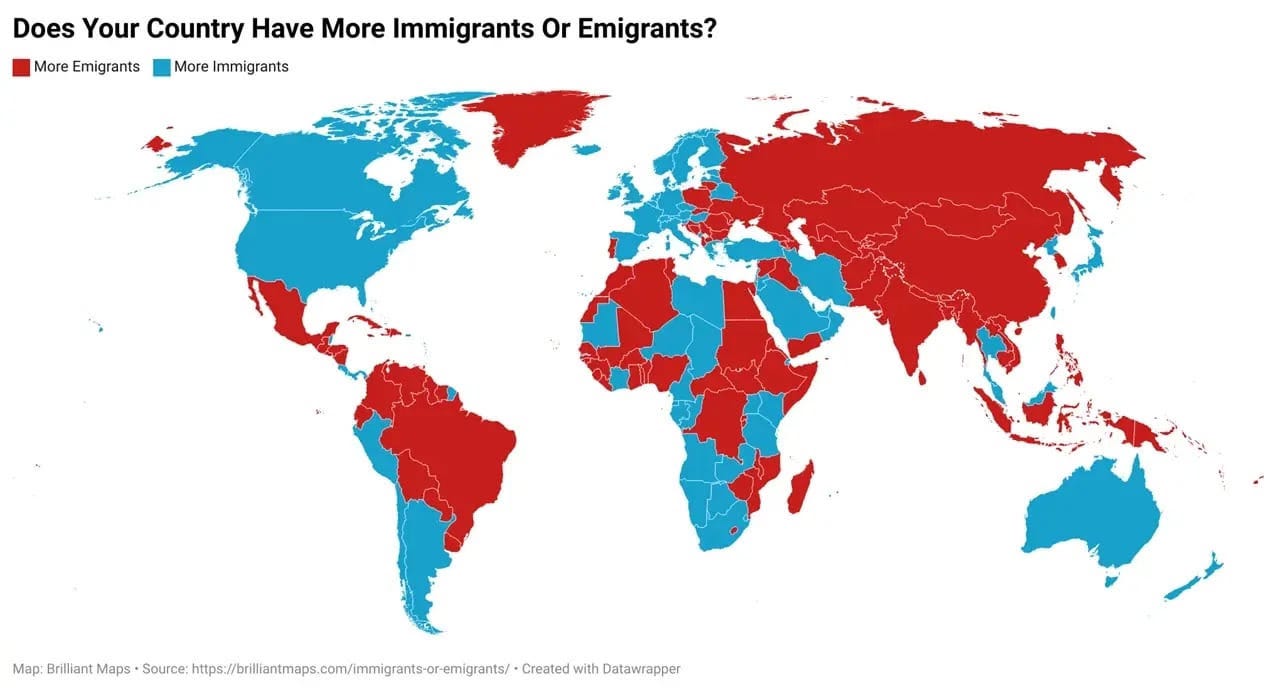

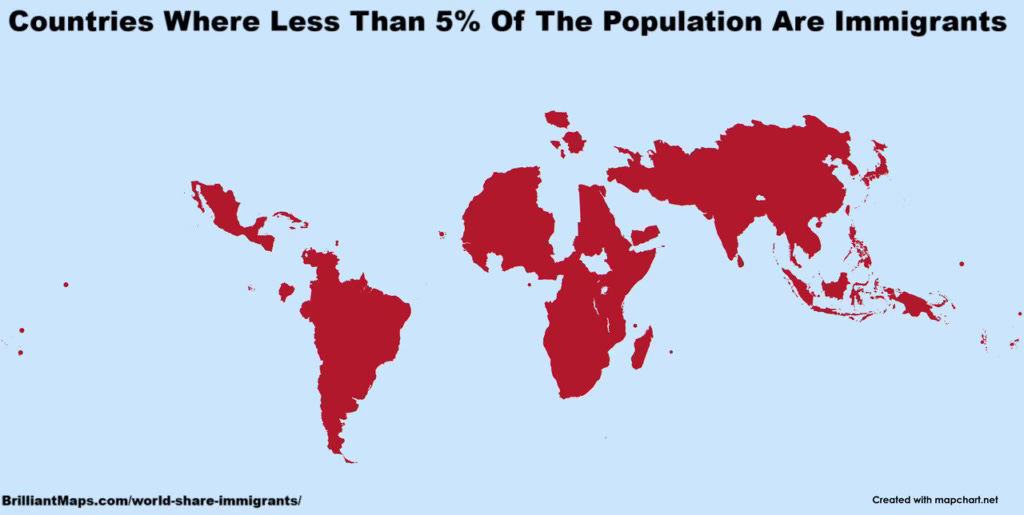

Brilliant Maps

The website run by Ian Wright sends me a steady stream of stuff. Here are things I found interesting. His maps, my comments.

No wonder Vladimir Putin is so land hungry.

There could be a lot of reasons for this, and I can only speculate. There are counties that people are leaving, like Guatemala, or that don’t allow people in, like North Korea or that has a xenophobic culture, like Japan. Then there are many countries that people are not dying to move to, Chad, Libya or Myanmar. There is war: Ukraine, Yemen and both Sudans. All this is just me musing and is probably politically incorrect.

Also these two maps, while interesting, don’t exactly match.

Surprsing that Brazil and Argentina, once the desination of so many Europeans, especially Italians, are now places with few immigrants.

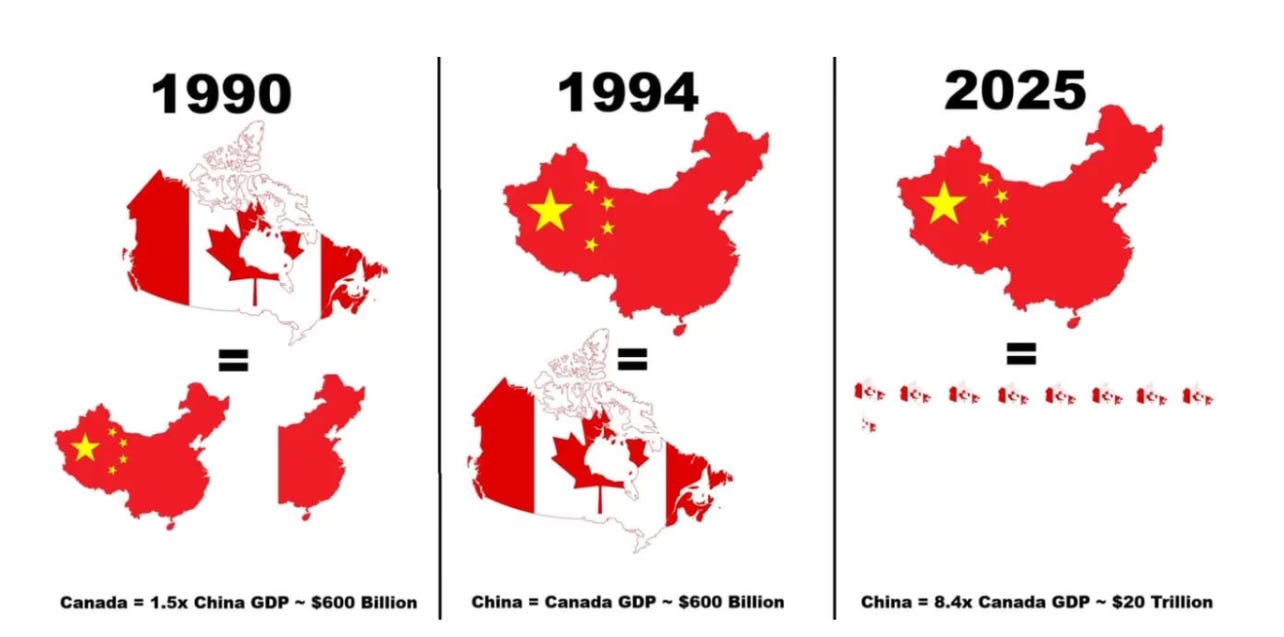

Canada vs China over 35 Years

I went to China in 1994 when Canada’s economy was equal to China’s. I remember seeing oxen pulling road building equipment. We visited a city where an entire new port was being built. There were state-owned factories that were empty, soon to be filled. I remember a young politician driving an Audi. He had the look of man on the make and he was the future of rich China, a capitalist state with a communist face.

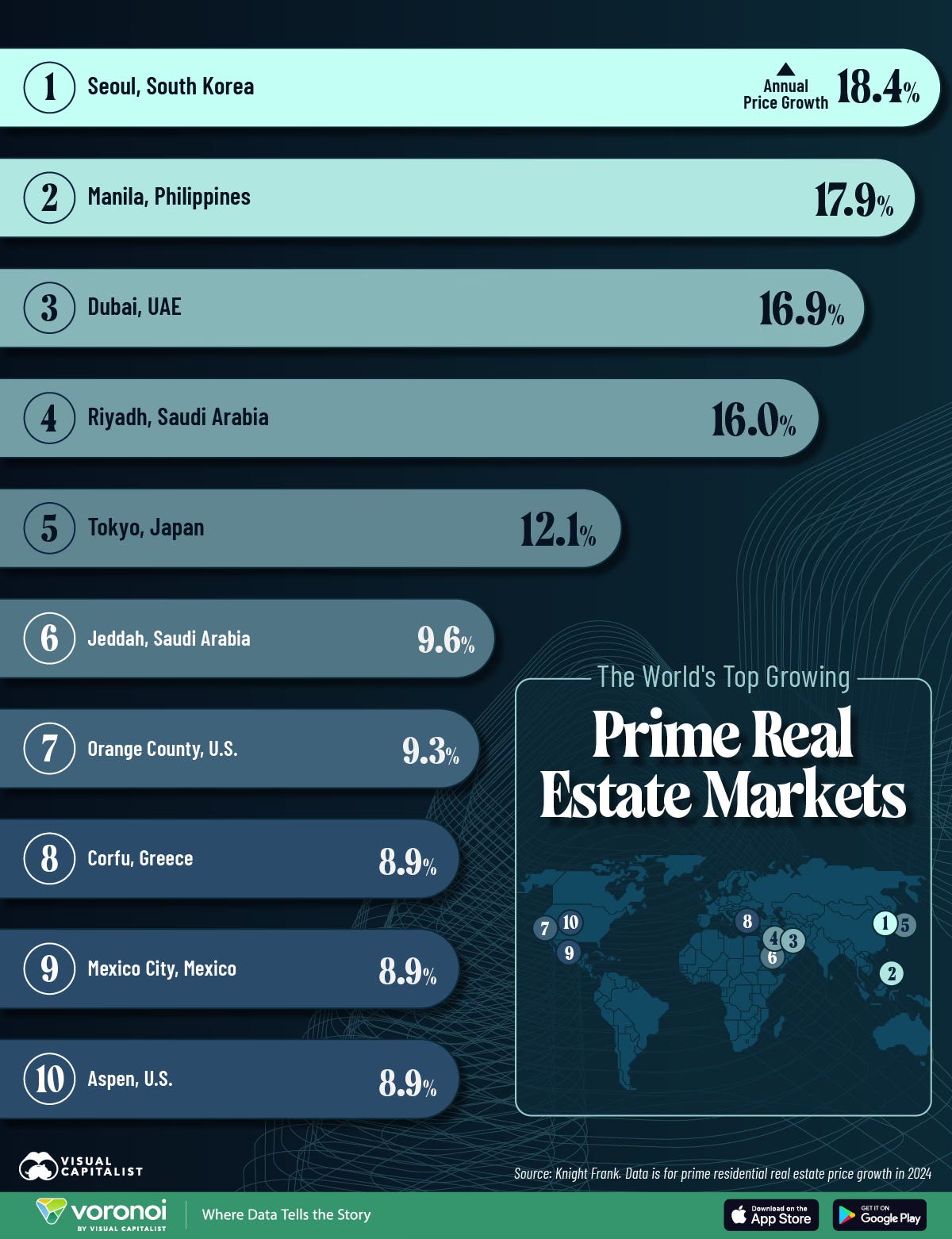

Someone’s Idea of Prime Real Estate

There isn’t anywhere on this list I would want to live after winning the lottery. Maybe Mexico City. Wouldn’t Riyadh and Jeddah be a barrel of fun?

But I Could Live Here; Where I am Now

The view from my apartment in Camogli on a quiet weeknight.

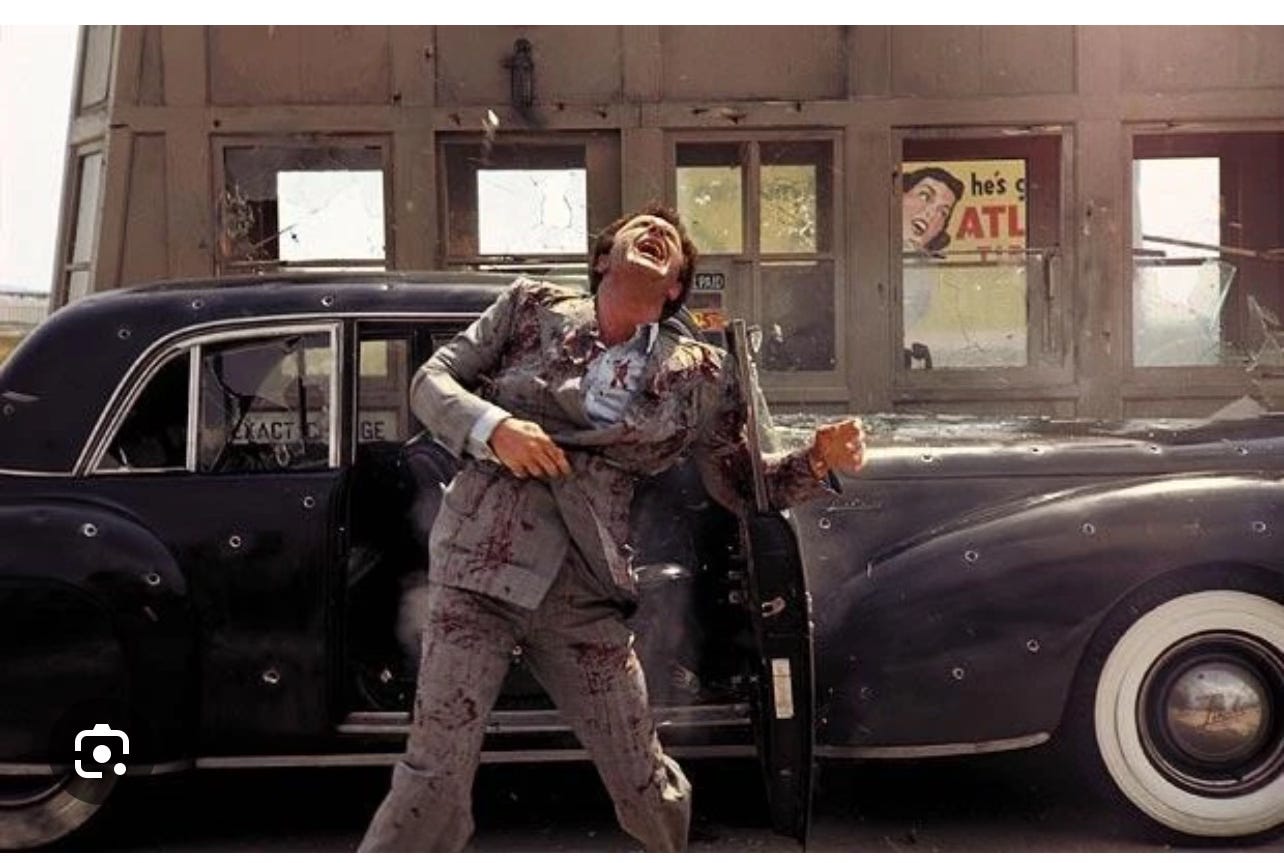

Want to Buy the Car Sonny Carleone Died in?

The Godafther’s son’s death scene at the toll booth and the 1941 Lincoln Continental.

And a 12 cylinder 1941 Lincoln Continental on sale in Hemmings Motor News. Only 1,250 were made. The average price is about $34,000. No bullet holes.

Essay of the Week

This is the first chapter of the second book I wrote as a ghostwriter and since I am in Italy, it is about an Italian. It is the life of Louis Aldrovandi. It is written in the first person in his voice. Louis was a delight to work with. He had a heart problem but everytime we would meet in a restaurant he ordered steak. The title of the book was A Lift to Life, because Louis went on to build an industrial company, LiftKing, that manufactured specialised forklifts.

Louis was 91 when he died in 2017. I went to his funeral. On the coffin was his wedding picture and a copy of our book. Here is the first chapter. It’s a bit long.

I was born Luigi Aldrovandi on January 27, 1926, in Via Castiglione Emilia Castelfranco Modena, a small town 16 miles (27 kilometers) from Bologna in the Po Valley of northern Italy.

Large families were the tradition in Italy then and I was the second of nine children.

We lived in a large farmhouse, with what is now called an extended family, in our case three generations living under the same roof. Along with my father Rodolfo, my mother Golinelli Selica, my brothers, and my sisters were my step-grandfather Guiseppe Marchesini (born in 1869), my grandmother Bolelli Cleofe, my uncle Gualtiero and his wife Barozzi Carolina and their children—my cousins—Dante (1929) and Gino (1933).

We always had two or three servants, one woman to help in the house with the chores and one or two men to work in the fields and the barns. There was a total of seventeen people along with two or three helpers living in the house at the same time. It might seem overcrowded to people now, but they were incredibly happy times, and I led an idyllic childhood. We had all the essentials of life and in particular a strong family. We worked together doing chores, helping each other, and then we all sat down at the same table four or five times a day.

We all ate breakfast together at 7 a.m., had a mid-morning snack at ten, lunch at noon, another snack around four thirty followed by dinner between six thirty and seven. I don’t mean to give the impression that life ran by the clock, since all this could change with the season when we were busy harvesting crops or seeing to the animals.

Our farm was a little more than fifteen hectares, about forty-two acres in the English measure. It doesn’t seem like much by Canadian or American standards, but it was incredibly productive. Because of the warm weather we could grow wheat on one field, harvest it in early July and then plant a crop of beans on the same land. We also grew maize or corn, along with canapa (hemp) and other crops.

We milked about twelve to fifteen cows, had two oxen to work the fields, and a horse. Every morning, I would get up at five thirty, hitch the horse to a wagon, and take our milk to the local cooperative almost 1 mile (1.6 kilometers) away. There and back took an hour. We produced about 40 gallons (150 liters) of milk every day and it was loaded in the wagon in 10-gallon (35 liter) containers.

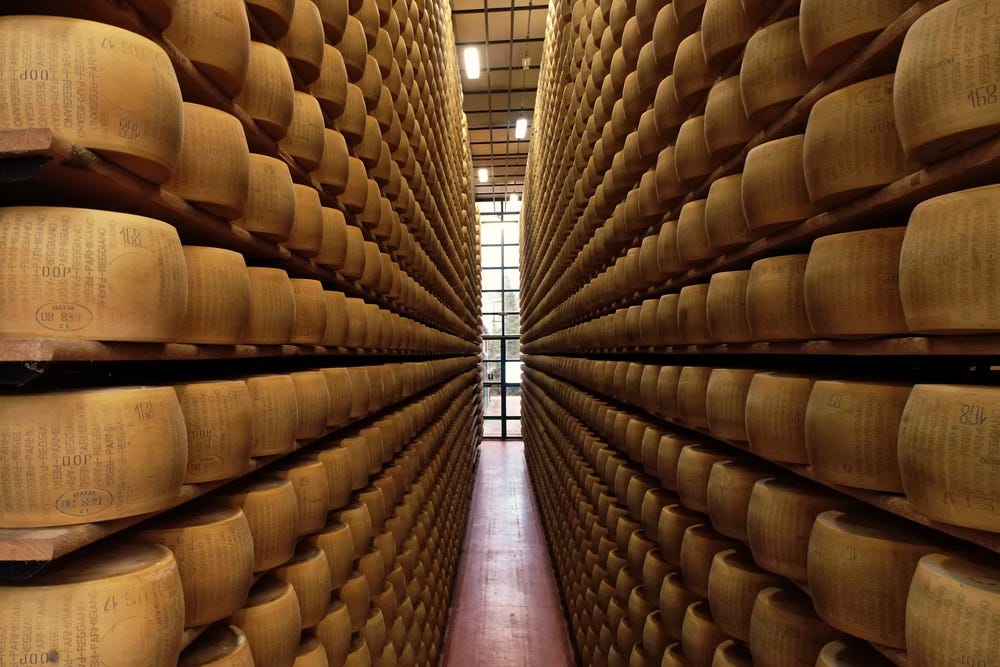

The cooperative took in milk from thirty to forty farmers in the region. The milk was used to make Parmesan cheese—we were close to Parma after all—aging it for three years. By the way, it takes about 211 gallons (800 liters) of milk to make one of those giant Parmesan cheeses that weight about 44 pounds (20 kilograms).

I would arrive back at the house by 6:45 a.m., eat breakfast, and get ready for school.

The trip to school from the house was 1 mile (1.6 kilometers) and I would go by bicycle to get there faster. The school went up to grades four and five or until we were ten or eleven years old. During the school vacation months, there was plenty of work to keep me busy on the farm from early in the morning until late at night six to seven days a week.

As our large family grew up, each one of us headed off in different directions. My older brother Enzo finished school by grade five. He suffered from anemia and was always sick and weak. I had to step in for him, as I was next in line. When I finished fifth grade, I went to an agricultural high school, the only high school in town, for three more years.

While family life was peaceful, politics in Italy were anything but. The Fascist Party under Benito Mussolini came to power in 1922, four years before I was born. The Fascists tried to control everything in Italy. For example, every Saturday (Sabato Fascista, roughly “Fascist Sabbath”), the children from grade school to university were forced to participate in whatever plans the party ordered. In uniform, we were made to attend parades, sporting events, meetings and whatever else they arranged. I quickly learned never to wear my uniform in the house as this would anger my father and he would order me to remove it. My father was extremely anti-Fascist and to see his son in uniform disturbed him deeply.

There were few political discussions in our home or around the table. One time, though, I recall my father commenting about Il Duce—Mussolini. I made a wisecrack about Mussolini being intelligent. My father said he had the intelligence and foresight of a pig! On another occasion, I said I had heard that Mussolini was transforming Italy into a new Italia. My father responded by saying, “Yes, it will be a ‘new Italia.’ He is destroying it completely.”

After the war, we found several newspapers dated from 1920 to 1940 that my father had preserved under the roof tiles that were all anti-Fascist in their views.

Just as the war started, I completed agricultural school and received a diploma, but I realized it was taking me nowhere. What I needed was a diploma from an industrial school.

During the summer, along with my two cousins Benito and Righi, I took a course at an industrial school in Crevalcore, 19 miles (30 kilometers) from our house. The school offered machine shop and electrical installations and that’s what we concentrated on. We also studied literature, mathematics, history, French, Italian, and geography. We all passed, and this allowed us to continue our studies at the Instituto Industriale Fermo Corni in Modena.

The diploma from the industrial school meant a lot for me since it opened up a whole new world, the opportunity to work in industry instead of just farming. I wanted to go to the school in Modena, but my father explained with the war on he needed my help on the farm. The two men we had working on the farm had been called up to the army. My brother Enzo wasn’t up to the task of farm work, so it had to be me.

My father felt bad about it; I could see it on his face. So, I came up with a compromise: night school. It was a three-year course in things such as electronics and mechanics. I chose electronics, and because of my summer courses I skipped the first year.

Once at school, I realized it was not going to be easy. The course was demanding, taught by an electrical engineer with a practical knowledge of how to apply the theory. Night school ran from six to ten, five days a week. The program alternated from theoretical to practical. The practical work had to be done in the laboratory. For example, to learn how to install an elevator, a large sheet of plywood was used. A drawing was mounted on the board indicating all of the controls, safety equipment, electric power supply, and the number of each floor as you pressed the buttons. We already knew all of the formulas, but we also had to know how to put things into practice in real life. We did similar things for transmission lines, transformers, and other areas of the electrical world.

The enthusiastic teachers made learning a pleasure. It might have been night school but were doing the same program as the day students. The only exception was that the day students were able to learn the academic subjects such as literature and history. It was unfortunate, but we didn’t have time for that.

Since the war was on, I bicycled from our home to school, about 7 miles (12 kilometers) each way. Fuel was rationed so public transport was cut back. The Instituto Industriale Fermo Corni was located in the opposite side of the city of Modena, so I had to cross the city twice a night. There was very little traffic on my return but on the way down, it was quite busy.

It was tough leaving the house at 5 p.m. in the fall or winter when it was almost dark. Often, I would ride with an umbrella to keep off the rain. Then there was the light on the bicycle, which had to be partially hidden so bombers passing over wouldn’t spot the highway. Modena was under a blackout order and the police kept a sharp eye to see we obeyed the law. The darkness could leave you so disoriented at times that you would end up in a ditch, spilling over and soaking your clothes and shoes. You could always get lucky and hitch a ride on a passing truck, grabbing on the back with one hand and having it pull you along. his could also be quite dangerous if you lost your balance or got squeezed between the truck and the line of trees on the side of the road.

My usual day started at six in the morning, and I worked on the farm until I was ready to leave for school at six in the evening. The work was hard and physically demanding. From September to November there was the preparation of the land for the fall, which included seeding. Farmland in this part of Italy was valuable, and every square meter had to produce grain, barley, corn, and canapa (that’s hemp in English and no, we didn’t smoke it). In November, when the ground became too wet, we started to prune all the grapevines and fruit trees and repair the supports in preparation for the next season. We did this until the end of February. During March there was spring seeding that included hemp, corn, barley, beans, and beets. April and May were the hay harvest. As I mentioned, we had a dairy herd in a large barn and their milk was our main source of income.

During the three years that I went to night school, I kept in close contact with my old agricultural high school, Scuole Secondaria Agraria di Agricultura in Castelfranco. The principal, Direttore Pierino Gaule, took me under his wing and encouraged me to keep studying agriculture. The first subject was the types and qualities of different breeds of cattle. This included the economics of milk production as well as meat and cheese products. This was a large and difficult field, but Dr. Gaule had confidence in my skills. He made me review all of the material and cerealicoltura, the cultivation of cereal, wheat and other grains. This was the main food source in Italy, the basis for pasta, for instance.

Italy had to import food, and the Fascist government was keen on what it called the “Battaglia del Grano,” or Battle of the Grain. It was aimed at making the country self-sufficient in wheat. The school co-operated with the government to promote this, and because of my farming experience and education, I was sent to speak at schools and public meetings.

One of the things I enjoyed was when I spoke at private schools where I could impress the sons and daughters of the rich with my use of technical terms, most of which they certainly didn’t understand. My talks were based on how to grow more grain using the best techniques from other countries such as the United States and Canada. I did this from the age thirteen to fifteen and it gave me a lot of self-confidence.

My main point was Italy had to put even more land to use and increase the annual yield of existing crops. In fact, in one year all public parks and the areas around monuments were transformed from flowerbeds to planted grain. That was very successful.

At the same time, I was also studying animal husbandry, in particular breeding dairy cattle. I was the top student in the schools of my district in this field, then in all of the schools in the province of Modena. I then went on to the national competition in Rome where I actually saw Il Duce, Benito Mussolini, one of the most famous men in the world at the time. Il Duce, means “the leader.”

In the national competition I finished seventh which was not too bad out of one hundred participants. Unfortunately, all my awards and letters of commendation of this period of my life were destroyed or lost when our house was taken over by the German SS and used as their command headquarters on the Italian front.

My teenage years were colored by politics, like everything else in Italy at the time. The Fascist Party organizers at universities, Group of University Fascists wanted me to take part in a number of competitions in cities across the country. It was an exciting prospect, but I was desperately needed at home. Just being asked to these competitions gave me lots of status with my friends. People usually had to seventeen or older to participate; I was only thirteen or fourteen at the time, but I had been so well coached by my teachers that I was a bit of a prodigy, so I was provided false identification stating that I was seventeen. For a young boy being over the age of sixteen meant that you could enter the houses of prostitution; I didn’t go of course, but I could taunt my friends that I was legal to, and they were not.