The Weak Ruble, Trade Routes of North America and a Police Reporter's Story

December 9, 2024 Volume 5 # 25

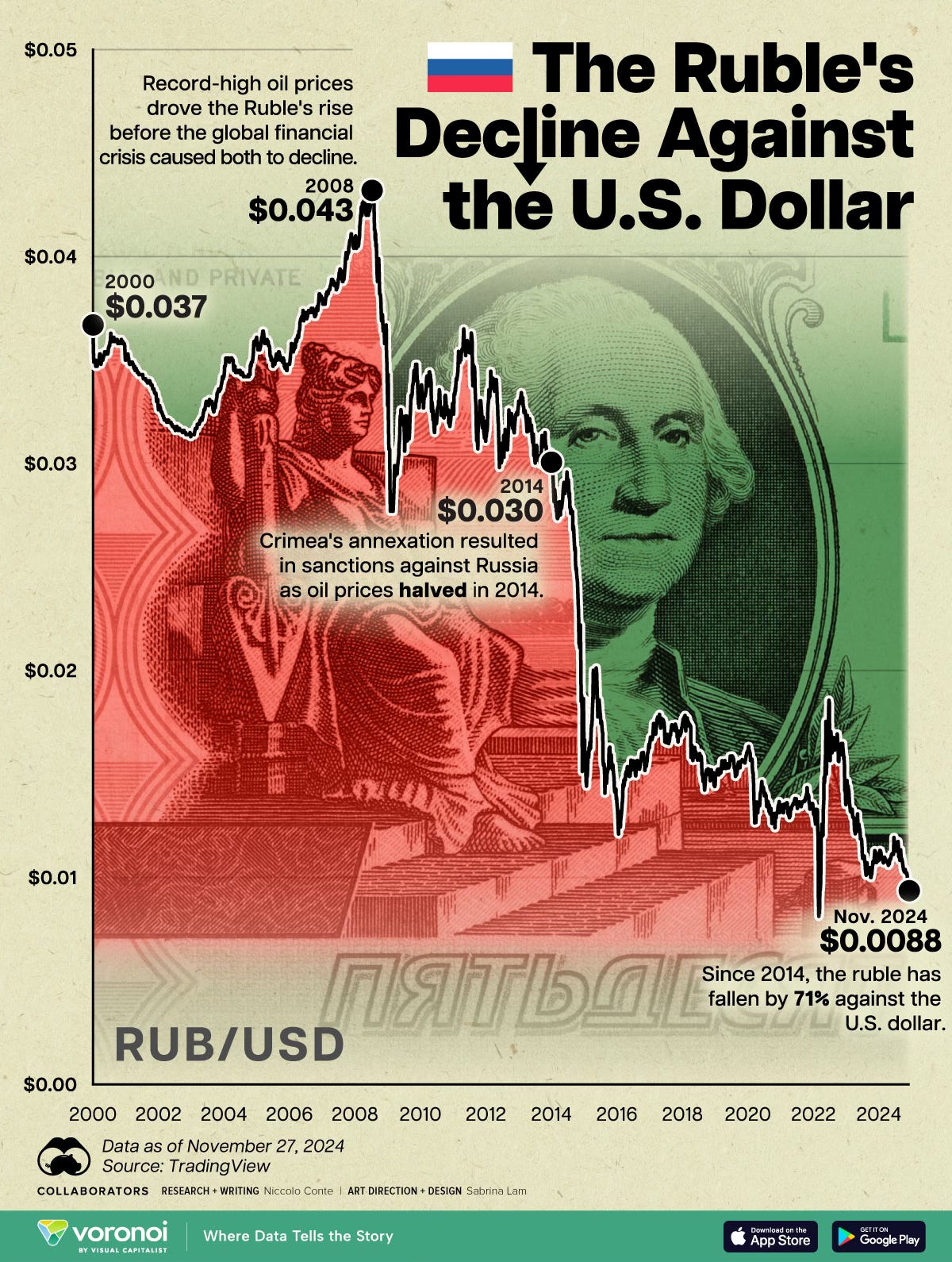

The Ruble: Putin’s Nightmare

It takes a lot of more rubles to buy US dollars and that is bad news for Vlad.

The Russian currency’s decline reflects the country’s economic woes.

“The current devaluation is far from catastrophic, but it’s a sign of a sick economy, suffering from both the enormously costly war against Ukraine as well as western sanctions,” says an article in The Spectator, the British weekly.

When the United States imposed sanctions on Gazprombank and other Russian financial houses, it led to panic buying of US dollars.

Putin boasted this week that 90% of Russian trade was now in rubles and other `friendly currencies’ such as the Chinese yuan. But the dollar haunts him.

It did tick up this week.

But the ruble is still weak over the long run. Donald Trump said on the weekend he wants a ceasfire in the Ukraine War. I am not smart enough to predict what that will do to the ruble, but you might think peace would help the Russian economy.

Trump’s election sent the price of oil lower -”drill baby, drill”- and that hurts Russia.

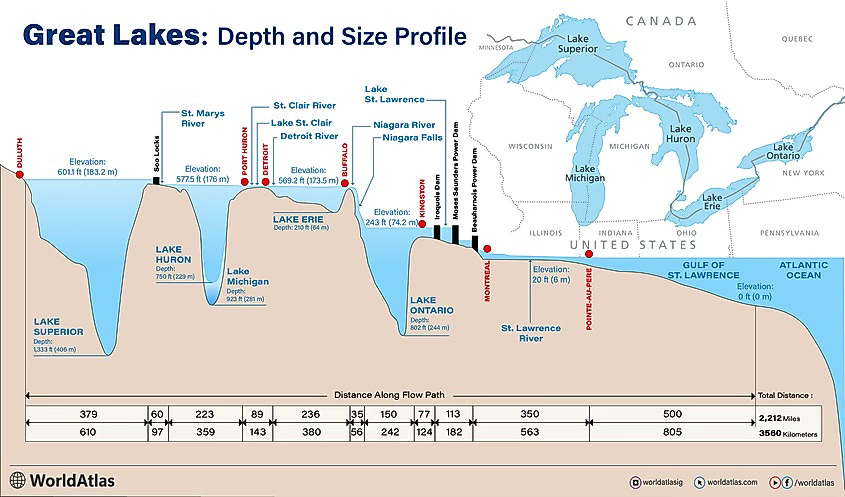

The Great North American Trade Routes.

Ships can travel 2,342 miles from the Atlantic to ports such as Thunder Bay, Ontario, and Duluth, Minnesota, on the far shore of Lake Superior.

The Great Lakes hold 21% of the world’s fresh water.

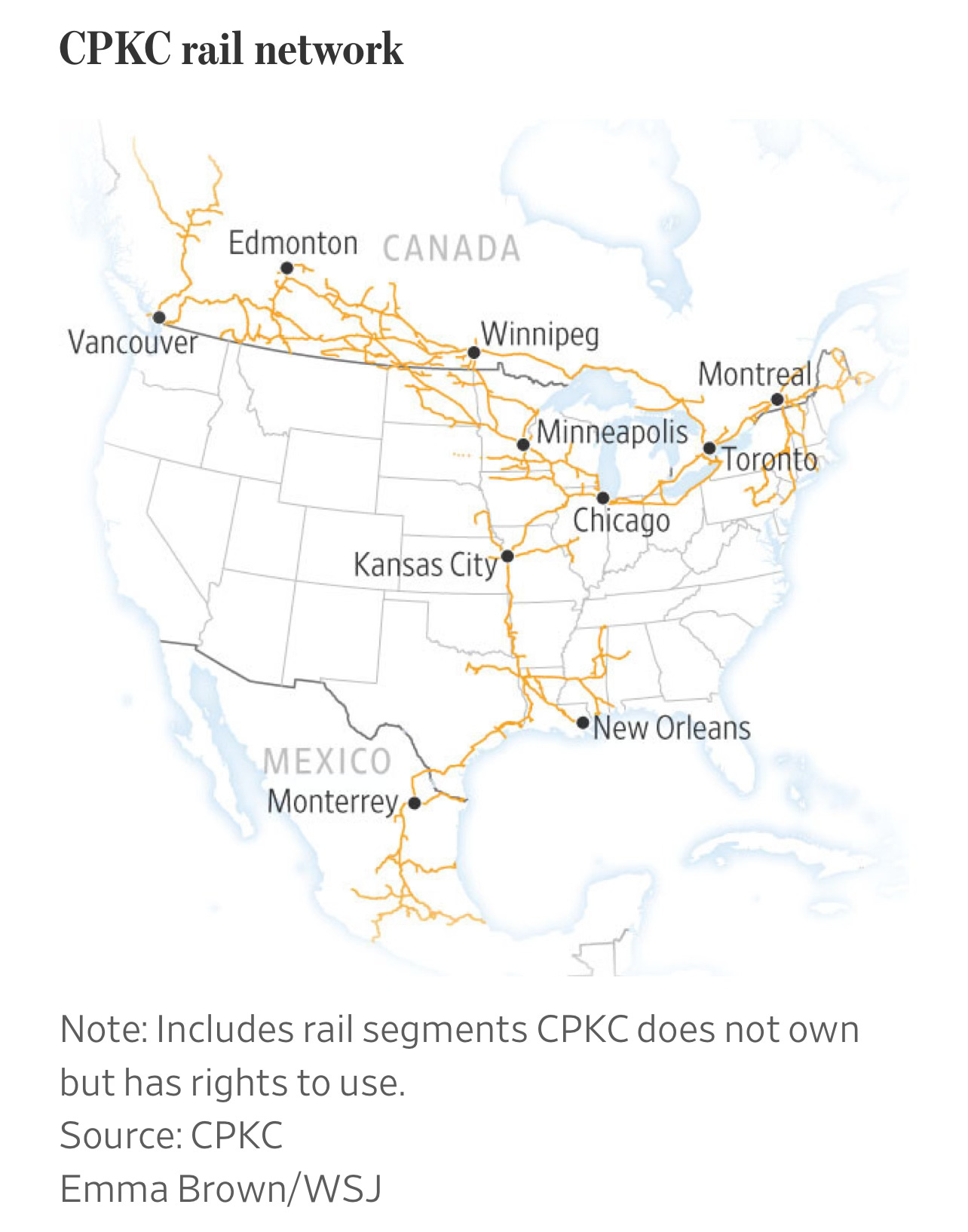

Continental Rail Network

CPKC stands for the Canadian Pacific Kansas City railroad, which stretches from the Atlantic to the Pacific and Canada’s oil sands to the Gulf of Mexico and deep into Mexico’s industrial heartland. The Wall Street Journal wondered what tariffs might do to the 20,000 mile network that connects three giant trading partners.

The stock market has already made a prediction. CPKC’s stock price is off since the election and Donald Trump’s threat of tariffs on Mexico and Canada.

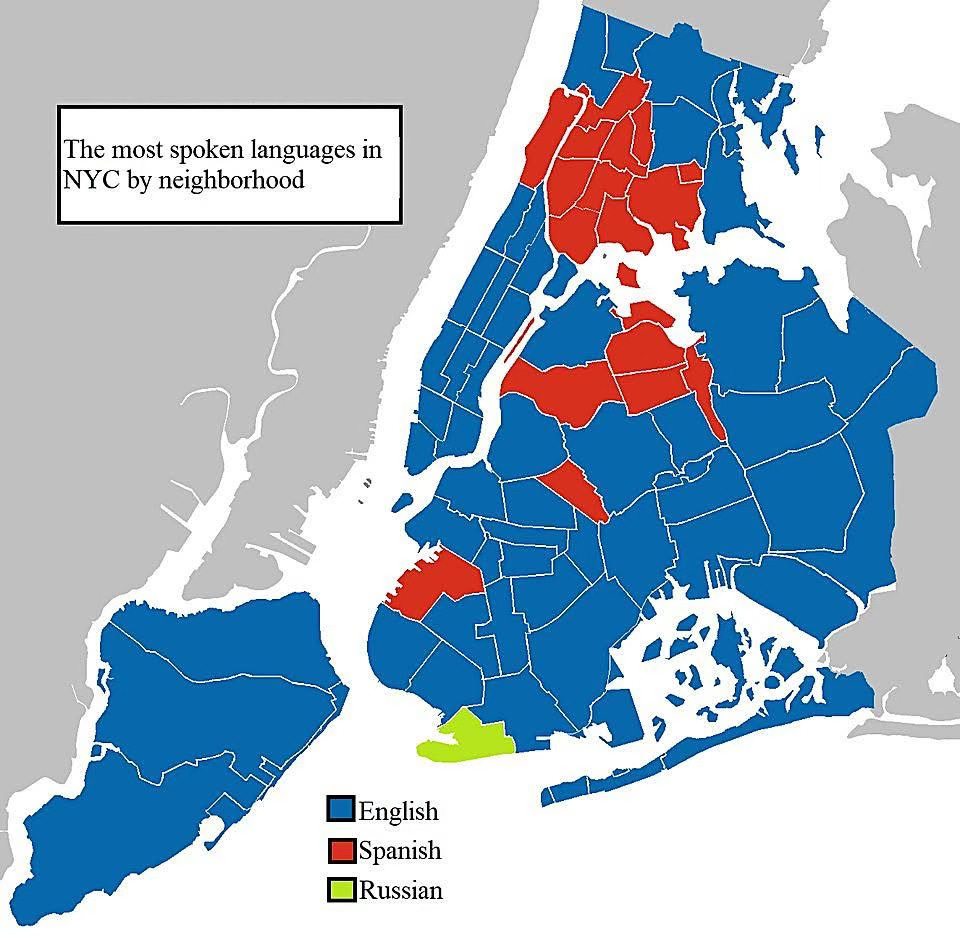

There is a Rose In Spanish Harlem

When Ben E. King wrote and recorded this song in 1960 the Latino population of New York City was less than a million.

There is a rose in Spanish Harlem

A red rose up in Spanish Harlem

With eyes as black as coal

Then look down in my soul

And starts a fire there

And then I lose control

I have to beg your pardon

I'm going to pick that rose

And watch her as she grows in my garden

I'm going to pick that rose

And watch her as she grows in my garden

Today there are 2.5-million Latinos in New York City, 28% of the population.

And speaking of Rubles, Russian is the third language of NYC.

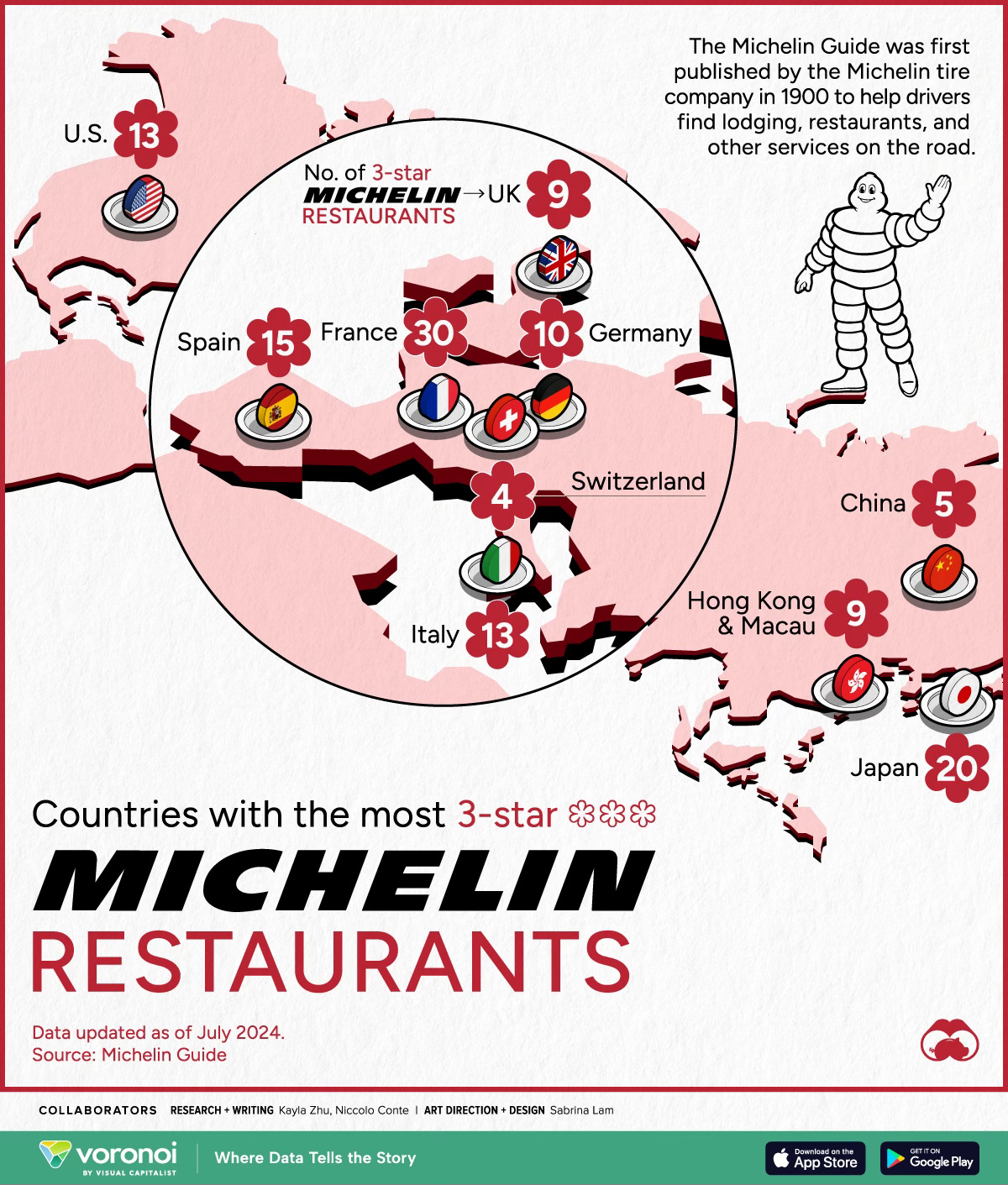

Worth a Detour

Many things are in life, and the phrase Worth a Detour is an understated recommendation from the Guide Michelin. Here are the 3-star rated restaurants. Not totally Eurocentric.

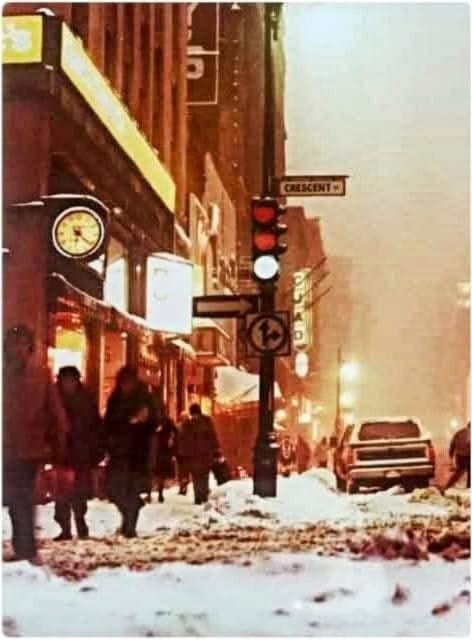

Snow at the corner of Crescent Street, Montreal, in the 1970s

Montreal cartoonist Aislin on the start of winter.

Essay of the Week

And a story that shows it can pay to be obsessed with crime.

***

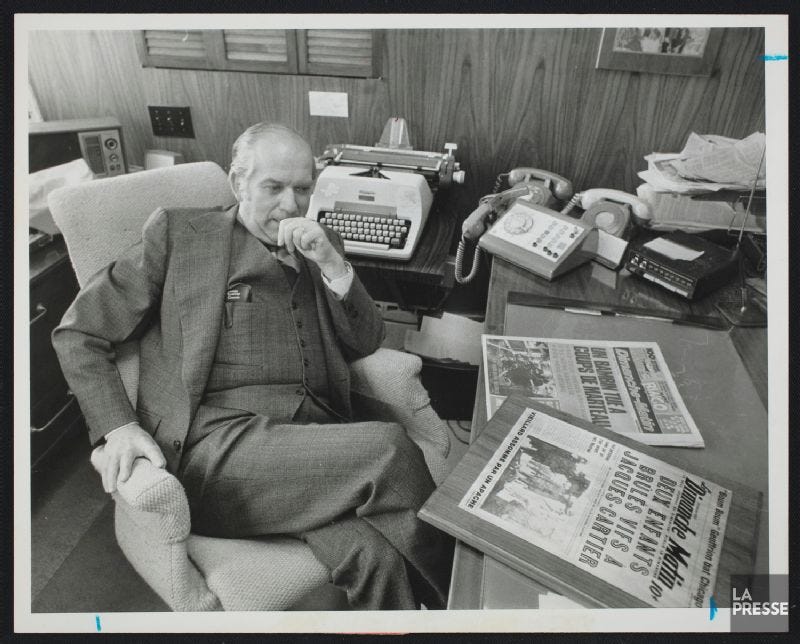

Jacques Francoeur never lost the instincts of the young police reporter. A businessman who owned the Unimedia newspaper chain with papers across Quebec and in Ottawa, he kept a police radio in his office, his car and beside his bed at home. He scanned the city and provincial police and the Montreal fire department.

“It drove my mother a little crazy at times,” said his daughter Josee Francoeur. “He would wake us up at night when we were small, shouting `girls, girls, there’s a fire on rue St. Denis’. He would put on his boots and hat and we’d head over.”

After the fire was over Ms Francoeur says the family would eat at Binerie Mont Royal, at maybe four o’clock in the morning. In spite of their baptism of fire engine chasing, none of the Francoeur daughters worked in the newspaper business.

Jacques Francoeur was another story. His own father, Louis, was a famous journalist in Quebec and a broadcaster at Radio Canada, the French network of the CBC. During the war he broadcast a program La Situation Ce Soir, (The Situation Tonight) in which he would brief French Canada on the progress of the war. He was multilingual, and could listen to English or German in one ear and translate it live into French.

After attending a number of schools, including College Notre Dame in French and Catholic High School in English, Jacques Francoeur started working as a reporter for the old Montreal newspaper, La Patrie, in 1941. He was 16 years old.

He soon built up a string of papers, writing in English and French for Le Petit Journal, The Montreal Star and the Gazette as well as the Ottawa Journal. Crime was his speciality and Montreal was a wide open city during the war years and into the 1950’s. Non licensed bars called Blind Pigs were seldom raided by police. Gambling spots run by gangsters specialised in a home grown dice game called `Barbotte’ which translates as carp, the fish.

In an interview with the Gazette many years later Mr. Francoeur modestly said some of his reporting on the Montreal crime scene helped lead to the Caron Commission on crime in the city. It was the start of a cleanup led by crusading lawyer Jean Drapeau, who would later become mayor.

Mr. Francoueur’s colleagues said his work on the crime beat changed the city for the better. “His reporting in the Gazette led directly to the Caron Commission and the firing of the police chief for corruption,” said Claude Poirier, a police reporter who worked with Mr. Francoeur for 25 years.

In 1950 Mr. Francoeur left the crime beat to buy a small suburban newspaper, Le Guide du Nord. He bought a few more suburban papers before starting his own Sunday newspaper, Dimanche Matin (Sunday Morning) in 1950.

Dimanche Matin was a newspaper where Mr. Francoeur could indulge his instincts as a police reporter. The paper loved the sensational and its star reporter was Claude Poirier, one of the best known crime reporters in the city. On Saturdays before the paper would go to press, Mr. Francoeur would sit with Mr. Poirier and maybe a dozen other reporters and editors in his office, order out for smoked meat or Chinese food, and go over the details of the next day’s paper.

Dimanche Matin was a huge success, with circulation rising to 300,000 at its peak. But eventually it was done in by competition, in particular from a Sunday edition of le Journal de Montreal, owned by competing Montreal press baron Pierre Peladeau of Quebecor. The paper closed in 1985.

“There wasn’t anyone as well connected in Quebec. He was on the phone to Prime Ministers Trudeau and Mulroney in Ottawa, Robert Bourassa (the former Quebec premier), and Lucien Saulnier (the man who ran Montreal under Jean Drapeau). He helped Rene Levesque by giving him a column in Dimanche Matin,” said Mr. Poirier, listing accomplishments in the machine gun delivery of the tough guy police reporter.

He said Jacques Francoeur would never miss a three alarm fire. For many years he was member of the Public Safety Commission of the city of Montreal, a position which gave him even greater access to visit crimes and fires.

“I covered a lot with him. The murder of Pierre Laporte, the DC 8 crash at St. Therese, all the big stories,” said Mr. Poirier. “He also made the careers of a lot of journalists in Quebec.”

During this period Mr. Francoeur also built up his media empire, naming it Unimedia Inc. At its peak it had 2,000 employees and controlled 30 major weeklies as well as important dailies: Le Soleil in Quebec City, Le Quotidien in Chicoutimi and in Ottawa Le Droit, a newspaper he had purchased from the Oblate religious order. Unimedia owned four printing plants, including an ultra modern one just outside Montreal that even printed New York Magazine.

The other big chains in Quebec coveted Unimedia’s properties. The firm was owned 90% by Mr. Francoeur and 10% by his accountant, Jean-Guy Faucher. Mr. Francoeur insisted his papers were not for sale. Even if they were, they might give too much control of the press in Quebec to two powerful media dynasties: the Desmarais family who owned Montreal’s La Presse, and the Peladeau family of Quebecor.

There was a hint in a Canadian Press article in 1986 when Mr. Francoeur was quoted as saying “There is always a price you can’t refuse.”

Soon he was receiving offers.

“We had been looking at his properties for 15 years. So I called him and he said `Here is my price’” said Peter White, the former vice-president and partner with Conrad Black at Hollinger. “There was no point arguing about the price. I knew if we haggled any deal would be over.”

The price was close to $91-million. Mr. Francoeur stayed on the board of Unimedia for several years. Though the sale to English-speaking owners, even those born in Quebec, caused some controversy, even the journalists union said it was better than concentrating ownership further.

At least $10-million of the proceeds of the sale was used to fund La Fondation Jacques Francoeur, which is dedicated to a wide range of charitable projects, including funding shipments of food to Sudan. In his personal life Mr. Francoeur had a wide range of friends, and was a gregarious outgoing man. One reason he became the confidante of prime ministers and business leaders was because he was pleasant and easy to talk to.

At one stage he was president of the Canadian Daily Newspaper Publishers Association and in 1982 was on the board of the American Newspaper Publishers Association. In 1985 he was granted an honorary degree in Commerce from Concordia, a university once named Sir George Williams College where he had been a night student as a young man. Ten years later, the university awarded him a doctorate. He was a Member of the Order of Canada.

Mr. Francoeur lived in a huge stone house at the top of Westmount mountain. Once one of the largest houses in the city when it was owned by a member of the Timmins family, it had been cut it half many years ago. Mr. Francoeur owned the biggest half.

Though he didn’t play golf he owned a golf course in Boucherville, just off the island, where he ate lunch most summer days, including last Monday. Later that day he played his regular game of bridge. Mr. Francoeur was active until the last week of his life. He worked at his charity and owned one small newspaper in Cornwall, the Seaway News, just to keep his hand in. He never turned off his police radio.

Jacques Gervais Francoeur was born on May 15, 1925, in Montreal. He died suddenly of a brain hemorrhage on Sunday, July 24, 2005. He is survived by his wife Catherine and four daughters, Lyne, Anne, Josee and Louise. There will a visitation at St-Leon de Westmount Church on Friday at 10 am, followed by a funeral mass at 11 am.