Trade War, Ratings War in US TV News, and Bill Marshall Flies a Biplane to World War II.

February 3, 2025 Volume 5 # 33

Tariffs: The World View

Everyone reading this already knows about the tariffs President Trump laid on Canada. The world thinks it is a super dumb move. The paycheque-to-paycheque voters who supported Trump will see higher prices almost right away.

The following are headlines from publications that many people would classify as right wing. None of them support a tariff war.

The Wall Street Journal

The Daily Telegraph

The Economist

The New York Sun and Conrad Black

Take a Valium?

A cartoon in the Montreal Gazette. Probably not a bad idea, but the Trump tariffs have enraged Canadians. In mild-mannered Ottawa, hockey fans booed the American anthem on Saturday. Justin Trudeau once called Canada a post-national country, meaning there was no patriotism. It looks pretty nationalistic at the moment.

One solution being bandied about is not relying on the United States as such a big customer. Fat chance of that happening. There was a recent plan to ship western Canadian oil to Eastern Canada. This map is from one group that objected to it. The Quebec government, with approval from Ottawa, killed the pipeline.

If that pipeline existed, Canada could sell oil and natural gas to the world.

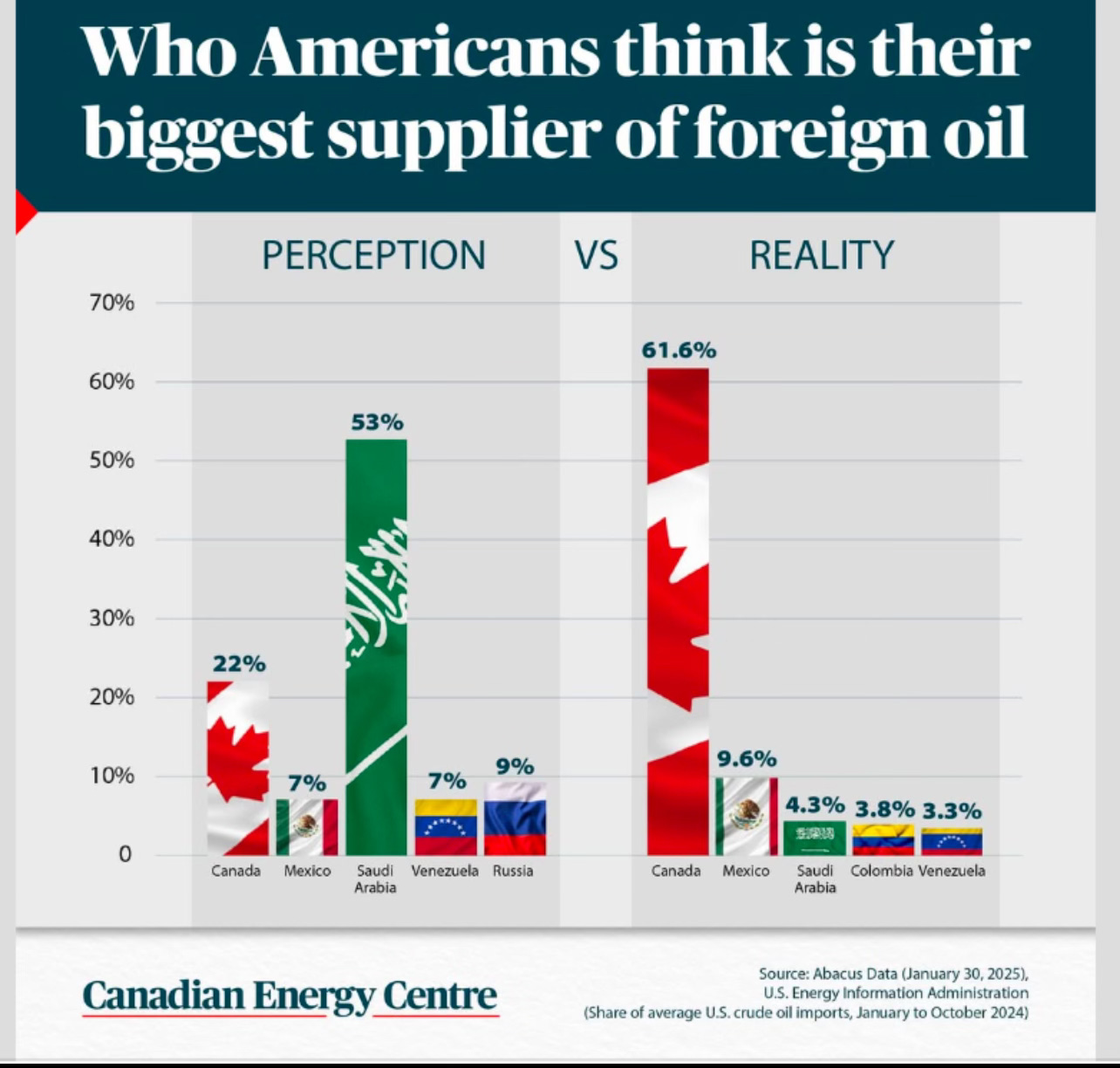

Speaking of Canadian oil, the tariff on it is just 10%. But few Americans have a clue about where foreign oil comes from. They think Saudi Arabia supplies it. Nope.

Commodity Trades

An interesting chart on its own, but of the 11 commodities listed here, Canada produces 9 of them, some such as Iron Ore, Aluminum and Oil in huge quantities. There is also uranium, potash and cobalt. We don’t grow coffee.

Canada can’t hope to win a trade war with the United States but the political and online chatting class are up in arms. When Conrad says something against Trump, you know it’s war.

CBS Evening News

The house that Walter Cronkite built saw a big change this week. First: two anchors, and they are men in white shirts, ties and suits: Maurice DuBois and John Dickerson.

On Wednesday the show started with a long, for a newscast, story on how American criminals are making big money bringing immigrants over the border from Mexico. Then news snippets, including the crooked Senator getting 11 years in jail, but without the standard report. Followed by an interview with a woman about to die from MAID in her bedroom. Gone is the tedious reports of the kind I used to do for decades. The old formula is boring and I hope dead. CBS Evening News ratings are up.

Beach Blanket

Taken on Tuesday at Sauble Beach, Ontario, on Lake Huron.

Essay of the Week

We are now coming to perhaps the most amazing thing Bill Marshall ever did: Try to fly a bi-plane from South Africa to England. Here is how he told me the story. I met Bill Marshall when Blast of Storm, a horse he was training in Barbados, was running in a race in Toronto. The horse’s owner, Sally Arbib, was someone I knew from my time in London. Her husband Martyn’s horse, Snurge, had won the Rothman’s Stakes in Toronto a few years earlier. I touched Snurge on the nose before the race and it won after a French horse was disquaified. The prize monye was about $680,000. Horse owners are superstitious and I was considered a lucky charm and was invited to more races.

Bill was regaling us with one story after another and Martyn suggested I write a book of his life. I was in. I went to see Bill and his wife in the hotel they were staying at near the airport and I brought a giant old atlas I had that was printed in the early 1930s. It matched the era Bill was talking about. “I tried to fly over the pink bits,” Bill said, refering to the colour of British colonies in Africa. Next, I spent five weeks in Barbados on two trips. It’s a rough life. Read on.

Up and out of Africa

Bill Marshall started his twenty-second year with a hangover. He and five of his friends from the gold mine had spent the night in a bar on the edge of Johannesburg, a place that was then so small he said it reminded him of Chichester, the seaside town in England where he grew up.

Though he remembered it that way, Johannesburg was in fact much bigger than Chichester. Fifty times bigger, or more. But it was made up of hundreds of suburbs, so the southern ones where Marshall lived and worked, near both the mine and the track, had more of a village quality to them.

Last night had been a birthday party of sorts. There was no cake. Gold miners aren’t the type to blow out candles. The bar on the edge of the city held a mixed lot, some black miners and their girlfriends along with the white men Bill was with.

“It was different back then, there was no apartheid,” he recalled many years later. “Black and whites worked together and they could meet each other after work. I’m not saying it was all harmony, but there was less tension between the races than say there is in England today.”

From the age of 14 Bill had been used to rough men. And these South African miners were as tough as the sailors on a tramp steamer or the loners living rough in Australia. The difference was they were richer. Although they all liked to drink, the work was too hard to be hung over every day. And the pay was too good to lose because of a string of hangovers.

Bill was rich, or at least richer than any 21 year old would be back in England. He had fourteen thousand South African pounds in the bank, no bills to pay and for the past year he was the owner of an old Tiger Moth, a biplane that was a lot sturdier than it looked. It had cost him three hundred pounds, a young man’s annual wage back in England.

Soon the work would be no more. Bill had just a week or so left before he quit. He was certain there was going to be a war and he wanted to be home for it, even though he’d already spent a third of his life away from England, it was still home. He read the Johannesburg Star every day. The stories of Germany and its it designs on England fired up the patriotism he learned as a schoolboy.

He knew the Royal Air Force would need pilots and his plan was to fly the 5,600 miles from Jo-burg back to England. That was 5,600 miles as the crow flies. They way he planned it would add another thousand miles, easy.

The night had been cool, maybe dropping below 60 degrees as the high plateau was swept of heat after the sun went down. Bill used to laugh that Johannesburg was so high it was a third of the way up Mount Kilimnjaro. That of course was a place he would never see, since his trip across the continent of Africa would not be up the middle but along the edge, where he could keep the sea on his left and the land on his right and petrol stations within easy reach.

The morning started warm and looked like getting hotter. The paper said it would get up to 85. But it was perfect weather for working when Bill arrived at the small airfield at Baragwanath just north of the city. He pulled up his old Austin and walked over to the man working on the plane beside his. He remembered he wasn’t a talkative man, but Bill could bring just about anyone out, and he knew a bribe always helped.

“Good morning,” said Bill and the Afrikaner just moved the side oh his head in acknowledgement. All Bill could see was back of his neck, leathery and criss-crossed with thick fleshy lines, the marks of so many years in the sun. Bill got right to the point.

“I wonder if you know anyone who wants a car in return for a few hours work on my old Tiger Moth?”

***

A Tiger Moth bi-plane in the skies over South Africa. The plane had a mxiumum speed of 109 mph and a cruise speed of 67 mph and range of just 302 miles (486 km) with a standard fuel tank. Its ceiling was 13,600 feet, or 4,100 metres.

The neck pulled its head from inside the cockpit.

“I might just know a man,” said the Afrikaner in an accent that set him apart from Bill and the other English people. If you hadn’t lived in South Africa for a while you might not pick up much of what he said. “What would you want done?”

Bill put on his full smile and watched as the Afrikaner eyed the old Rover parked two planes away. It wasn’t worth more than seventy or eighty pounds, but cars might be hard to come by if there was a war.

“I want to take out the second seat and fit it with extra tanks. Need the extra range. And I want the engine checked over. Oil changed, that sort of thing.” He paused. “You reckon you could do it?”

“By when, man?”

“A week, no more.”

The Afrikaner knew the Tiger Moth. It was a trainer, with dual controls in the front and back. He’d have to haul all that out, saving what parts he could, and then weld in a new fuel tank. He’d have to fashion some kind of turnover cock, so it could feed into the main tank. It might take him four days.

“Take me two weeks. There’s lots of work left on this plane. First week in September. And that’s the car over there?” He climbed down out of the plane to walk over and take a look.

“Two weeks it is,” said Bill and the two men shook hands.

Hitler walked into Poland on September 1, 1939. Chamberlain declared war on September 3. Bill Marshall took off for England on September 6. A wind blew across the plateau from the west he took off into it, the sun peeking over the eastern horizon a little past five in the morning. The Tiger Moth eased into the air without a worry in the world, though it was carrying enough petrol to turn it into a bomb if there was any mistake.

Inside the open cockpit Bill carried some water in a couple of old military surplus canteens, a few sandwiches and a couple of slices of cold meat in his pockets, some fruit and a good atlas he’d bought at W.H. Smith in Johannesburg. Since Johannesburg was already more than five thousand feet above sea level, he'd have to fly low for a while, at a couple of thousand feet.

The plan was to follow the roads in South Africa, hugging border with Bechuanaland. It was almost straight west, but not quite. To keep close to places where they might have petrol he had to follow the roads. He’d already planned his first stop, a Uppington, a little town in the middle of nowhere in the northern reaches of the Transvaal.

Like most of the pilots in Africa, Bill Marshall was self-taught.

“There were no instructors, at least not any I knew. We just took the plane out and popped it off the runway a few times, getting the feel of it. Then you took it into the air. One you were up there you had to figure out how to get it back down. The Tiger Moth was an easy plane to fly. It lifted off like a feather. There were no flaps or landing gear, nothing complicated. You just flew it.”

Fitted out the way it was, the plane had a range of about 600 to 700 miles, depending on the headwind. On a good day he could make 1,000 miles, but the wind would have to behind him and it helped if there wasn’t much in the way of clouds. The Tiger Moth had instruments, but just an artificial horizon and a compass. Not a plane you wanted to fly at night or into the clouds.

The Tiger Moth had a top speed of 140 mph, but that would burn too much petrol and be hard on the engine. He would hope for an average of 110 mph over the ground. He and an engineer at the mine had sat in an office with the atlas out on a table. Over a couple of beers after work they figured out his route. The big rule: stick to the pink bits. Whenever possible land in a place where they fly the Union Jack.

The ruler told them the run to the Atlantic Ocean was about 900 miles. But with just one stop and he hoped he could be in the British Port of Walvis Bay by sunset.

The first refueling stop he picked was Upington, a town in the middle of nowhere on the border with South West Africa, the former German colony the British had been running since the end of the First World War. He followed the roads from Johannesburg, heading west out to Mafeking, the place where the founder of the Boy Scouts, Colonel Bade Powell, held out against the Afrikaners in the Boer War.

Flying over the town Bill thought of the jingoistic stories he’d heard about the siege. Even at 21 he was little more cynical now. He left home so young he never had a chance to become a boy scout himself. Turing southwest at Mafeking, he followed a series of roads and rivers until just after nine noon he made could see Upington on the horizon.

From the air Upington looked like an oasis in the middle of the Kalahari. It sat beside the Orange River, and Bill though it was wider than he expected. The river produced a burst of green, like water does in any desert. There was an airstrip there and he touched down a little after ten in the morning. He did a quick mental calculation and reckoned he’d averaged about a hundred and fifteen miles an hour. He would have to keep the revs down on the next leg to make sure he had enough fuel.

The Tiger Moth feathered down and he taxied to the petrol pump beside the hangar. The thermometer on the side of the building said it was 75 degrees. The few clouds were miles high. Perfect weather for the run across the desert, the first run of iffy flying on his long trip. In his map he’d marked out the tracks across the dry strip from the Northern Cape to the middle of South West Africa. He didn’t plan to touch down in what was once German territory, since some of the old colonists might not like the idea of his going home to fight the Germans. For that matter, he had told the Afrikaner where he was going, but not why.

“Going far, mate?” asked the boy manning the pumps. He was maybe a couple of years younger than Bill. Again, no need telling people where he was going just yet.

Bill flashed his smile and answered, “Walvis Bay. Got to meet someone before dark. It’ll take more juice than normal. There’s a tank in there where the seat should be.”

Bill was already out stretching his legs. He made small talk about the modification and the best way to fly to Walvis Bay, though he’d already picked his route.

“You have o watch that dessert, man. There’s nothing down there. No petrol stops.”

Bill nodded and asked where the water was. He went over and filled up his canteens. This was going to be a long run.

As he revved his engine for takeoff, Bill looked at the watch on his wrist, a Rolex with a black dial he’d won in a card game in Jo-burg. It was little before ten o’clock. He had seven hours until the late winter sun went down in Walvis Bay. The route he’d mapped took him along the roads across the bottom of the dessert. He too the plane up to eight thousand feet, where the air was cooler and thinner.

Four hours later and could see the Atlantic ocean for the first time in more than five years. It was where the road ended. Luderitz, the asshole of the universe, and a German speaking asshole at that. As he moved out over the water, the change in temperature sent up thermals that buffeted the Tiger Moth about a bit. He moved a mile or so off shore flew along the coast.

“Shit,” he yelled out loud as he heard a sputter in his engine. It coughed again and he jiggled the fuel cock that handled the line to the extra tank. Nothing. The propeller changed its shape as its revolutions changed, as it was starved of power. Bill shut the engine down.

The altimeter read four thousand feet. The wing area of the biplane gave him extra lift, so he could ride the currents almost like a glider, though not forever. The engine was an anchor, pulling him down to the ground, though he had lots of time to look for a place to land.

“Damn that Afrikaner,” as he spoke to himself out loud, figuring he could think with a clear head if he could hear himself. “Paid the bastard to tune this thing and I’m stuck with a clogged fuel line.”

That’s what he had to tell himself it was. As he floated down he look for a place to touch down. There was lots of sand, but also rocks in the dessert. And the sand could be soft. Instead he saw a beach and hoped the tide had been out long enough that the sand was good and hard. He was too young to even think dying, all he wanted to do was fix his plane and make to Walvis Bay before nightfall.

The wheels hits the sand as if it were tarmac. Hard. The tide was out. The plane stopped and Bill stepped out on to the wing and jumped to the ground. Within a minute he’d found the problem. A clogged line. He took the tube off and blew a piece of dirt or clogged up oil and then put it back. The engine fired up and he was back in the air five minutes after he landed.

Did it cost him any fuel was the question? It was almost three o’clock and he didn’t know just where he was. This was a stretch, though the wind had been neutral since he turned north. At least the engine was back to normal.

The sun started to change colour and drift farther west. The altimeter told him he was five thousand feet above sea level, about the same place he was when he left Johannesburg that morning. The time was five past four. Her at the edge of the single time zone that crossed South Africa, it was less than a hour before dark. He started to do mental calculations about how long it would take to drop down and find a place to land.

Bill pulled on the throttle and moved the revs up, maybe giving himself another twenty miles an hour over the ground. Maybe not the right decision but he decided to go for it. AT fur thirty he saw smoke from a ship in the water, and he reckoned it must be heading for the deep water port at Walvis Bay. Then he saw a road, and he cut back on the throttle and headed down for land.

The railway tracks were what he looked for, passing the town and head to where the tracks from the interior met the sea. He knew there would be petrol and flat solid place to land. It was quarter to five when he touched down; with, it turned out, enough fuel to go another hundred miles, easy.