Trump Tarriffs Hit Shipping Rates; Panama Canal; Hiding from Nuclear war and Another Bill Marshall DFC Chapter.

February 10, 2025 Volume 5 # 34

Tariffs Rock Shipping By Sea and By Air

The cost of shipping a container from China to the United States is rising and the threat of futher tariffs— Trump is musing about a 60% tariff on Chinese imports— means there is demand for containers to ship goods before that happens. Booking a 40 foot container from China to the US West Coast is now at $5,000 and $6,700 to the East Coast.

Freightos, the online shipping site, says Trump has also lifted a tariff exemption on small packages: “President Trump also suspended the de minimis exemption on imports from China, which means items under $800 are now subject to duties. This change is likely to have a huge impact on some e-commerce sellers, and could cause a sharp drop in air freight rates.”

Putting a package in one of those airfreight containers below now costs $5.09 a kilogram from China to North America. Odd, but the Trump effect could push airfreight prices lower, according to Freightos.

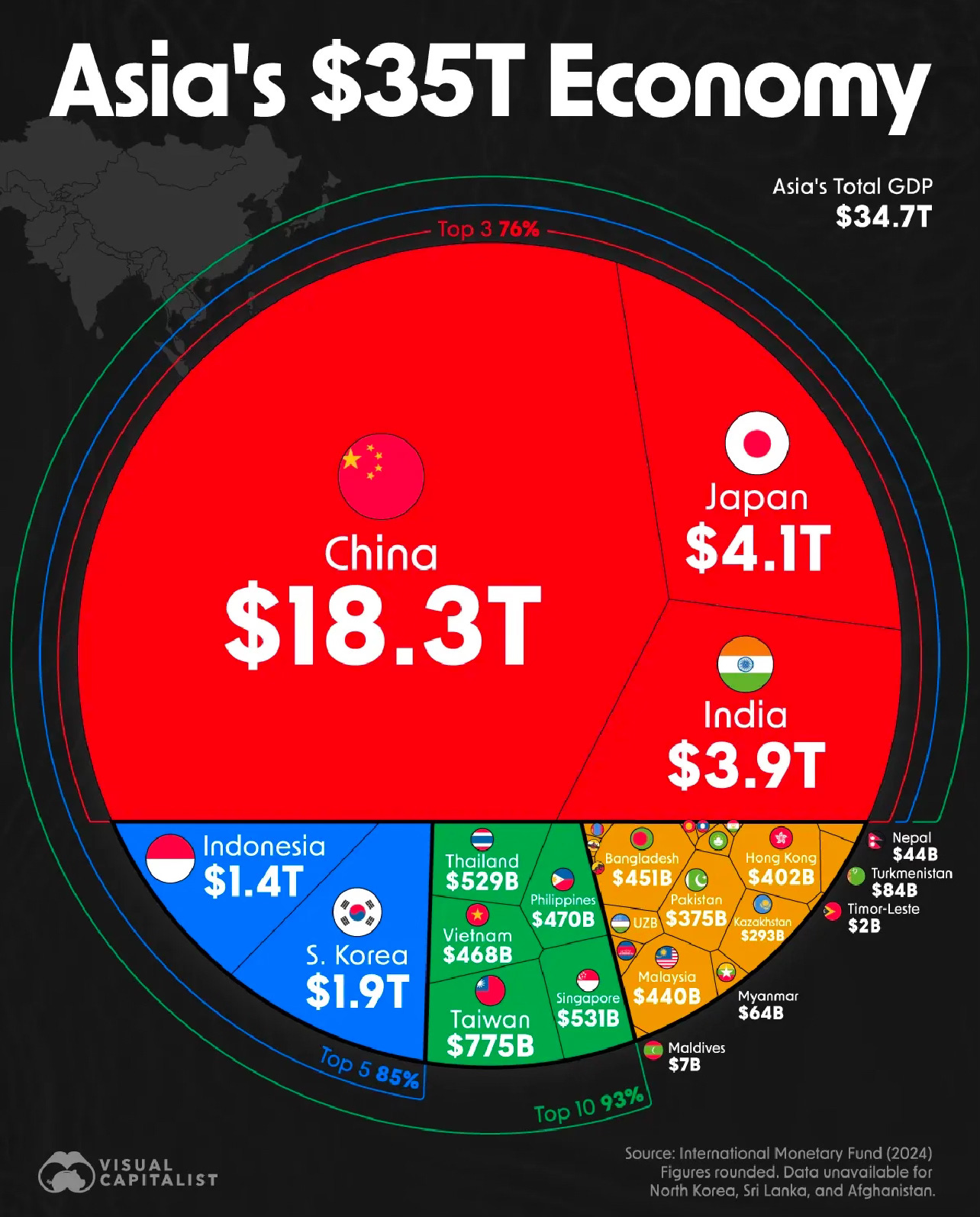

The Riches of Asia

Is India set to overtake Japan?

A Man, a Plan, a Canal: Panama

The Palindrome that is an ode to one of the two most important canals in the world. Because of trouble in the Red Sea, traffic on the the Panama Canal is just about equal to the Suez Canal, as ships are routed around Africa’s Cape of Good Hope to avoid Houthi pirates and missiles.

Look at the map and the Panama Canal doesn’t flow from east to west, as you might think, but northwest to southeast. The history is complicated, but Panama was a province of Colombia until it conveniently became independent in 1903 in time for the Americans to start building the canal in 1904. From 1903 the US created the Panama Canal Zone, which stretched five miles either side of the Canal. It was US-ruled territory, as American as Cleveland. Presumably this is what Donald Trump wants back, along with the power to set tolls on the Panama Canal.

The Spanish were the first to think about building a canal. In 1513 the conquistador, Vasco Núñez de Balboa stood on a mountain from where he could see the Pacific and the Caribbean Sea. He then waded into the Pacific.

The French, fresh from building the Suez Canal, started on their version of the Panama Canal in 1881. They wanted a waterway without locks, but that meant tearing down part of the mountain where Balboa stood. They failed. The US Army Corps of Engineers built the Canal and it opened in 1914, just in time for the First World War. American battleships, like the USS Iowa and Missouri, were built to squeeze through the narrow locks. Here is the Iowa in the locks with inches to spare.

Piccadilly Cutaway

Another transit hub, this one in the centre of London.

Two London undergound lines meet at busy Piccadilly Station. The Piccadilly Line is the deeper of the two; it runs all the way to the airport at Heathrow. The upper line is Bakerloo, which opened in 1906, the same year the Piccadilly Line started.

Here’s a Gruesome Thought

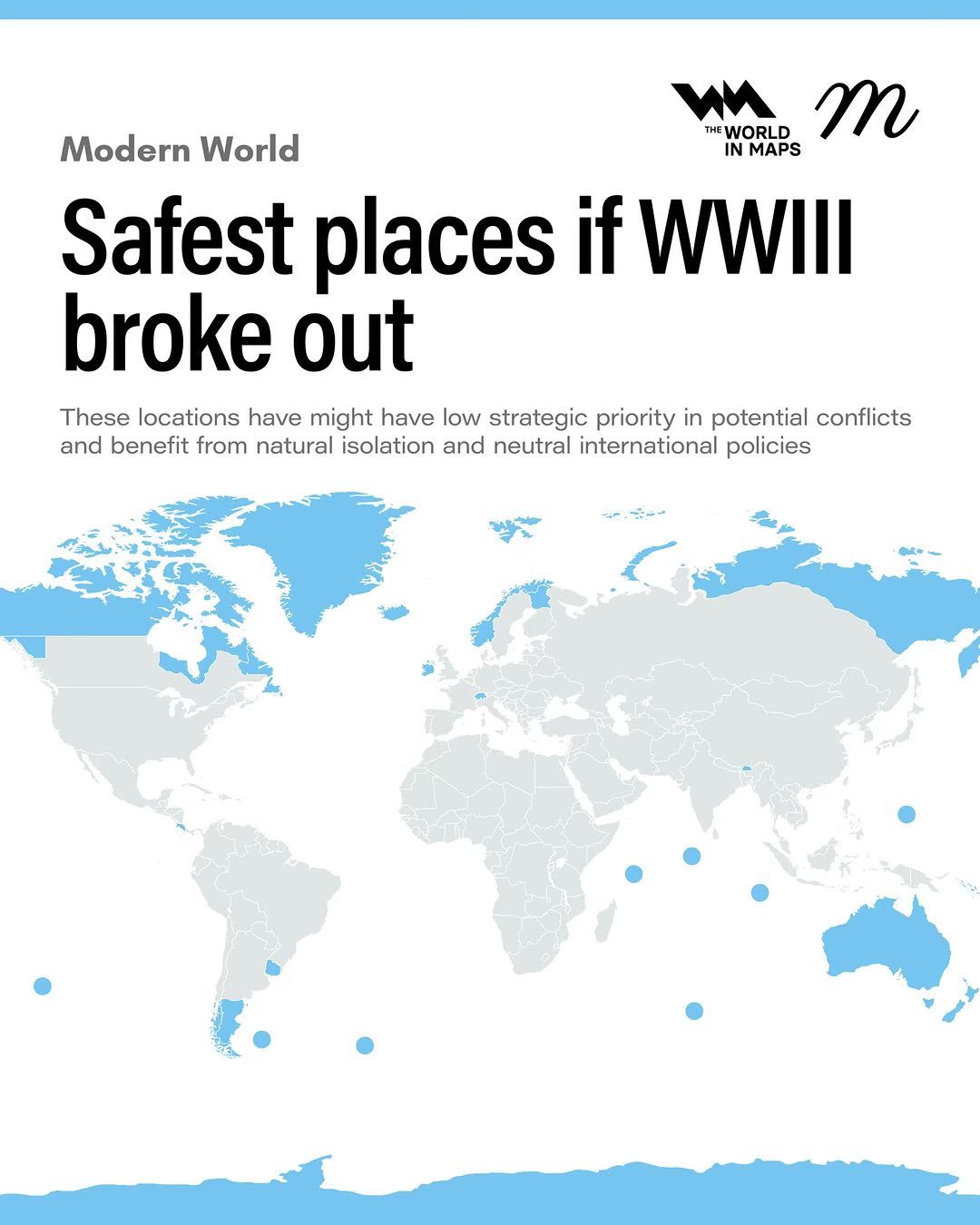

If a nuclear war breaks out, where do you want to be? Head down under, or way up top. Newfoundland’s safe. Shute’s On the Beach was rather prophetic about Australia.

Head down under, or way up top.

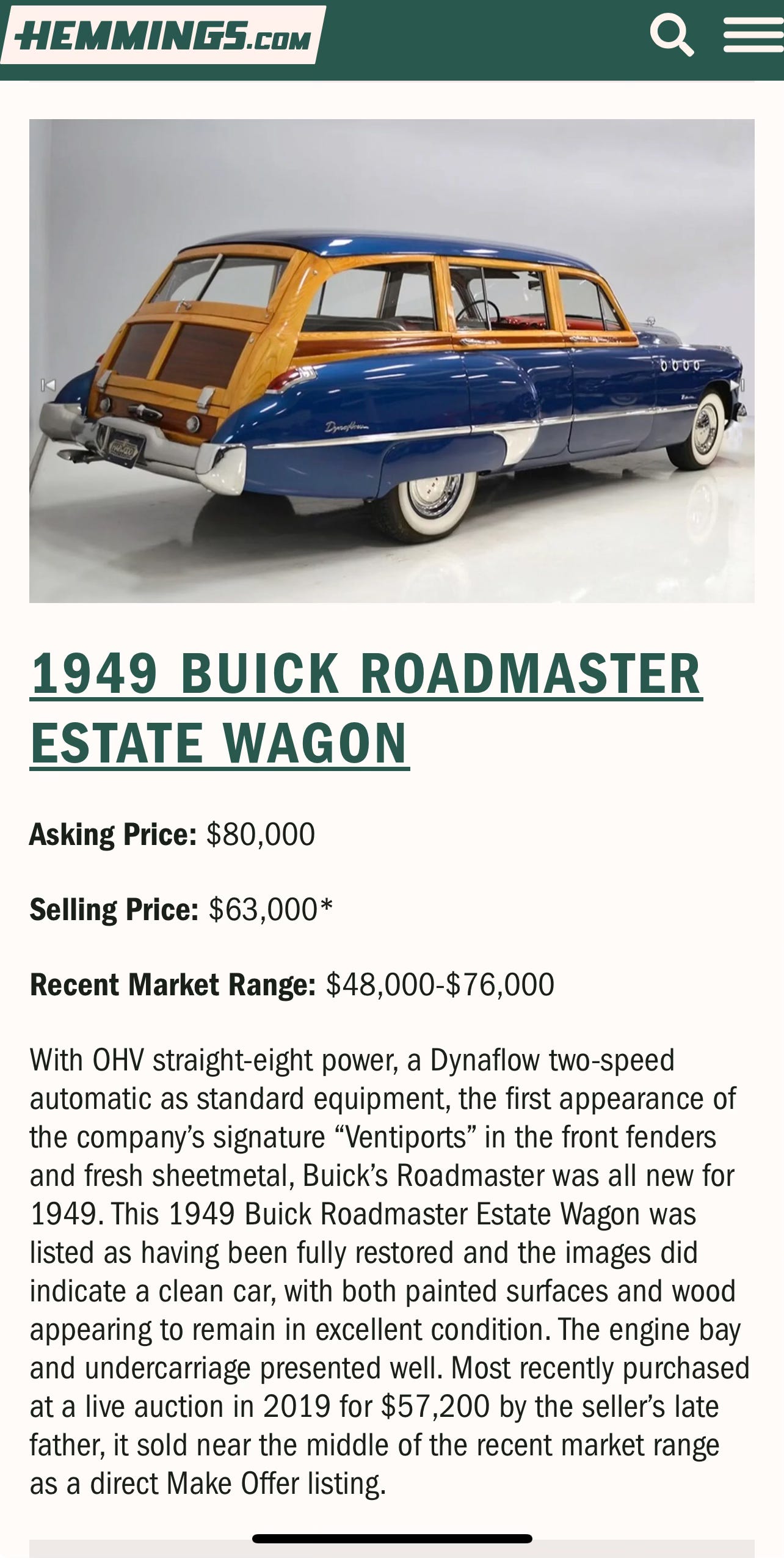

We’ve got a ‘49 wagon and we call it a Woodie (with apologies to the Beach Boys)

This is a posting from Hemmings Motor News which, among other things, operates an online auction site. This Buick Woodie Wagon is amazing. You can imagine the owner would only use it to run errands in the summer in Nantuckett or drive from the gated community in Florida to a safe shopping centre. It sure is beautiful.

Essay of the Week

This is another chapter from the book I wrote on Bill Marshall DFC about 25 years ago. At this stage in the story Bill is flying his bi-plane, a Tiger Moth, from Johannesburg across Africa in September of 1939, hoping to get back to England to join the Royal Air Force and fight in the war against Hitler.

The Unknown

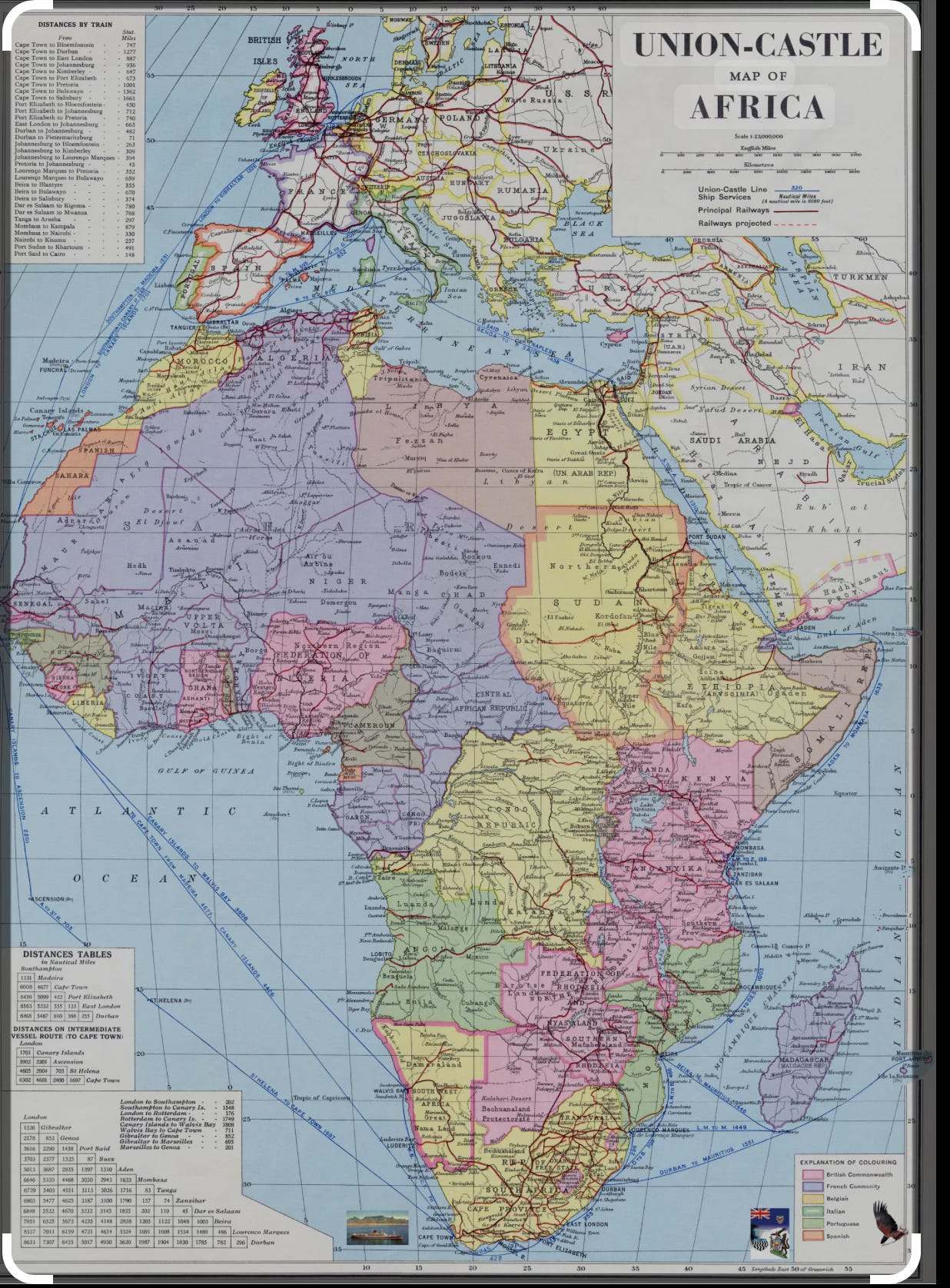

Standing beside his plane in Walvis Bay Bill Marshall still had to cross the great unknown, the patchwork map of colonial Africa. No one today would recognize many of the names on the map of colonial Africa. It was all about to change because of the war Bill was racing to join, but then no one knew that then. At the end of the first week of September in 1939 it all seemed as if it would last forever.

A pink British band ran up the middle of the continent: South Africa, Southern Rhodesia, Northern Rhodesia, Tanganyika, Kenya and the Anglo Egyptian Sudan, touching the Red Sea. Off the to the right, British Somaliland on the Gulf of Aden, and to the north, the island of Cyprus, protecting the entrance to the Suez Canal.

Along the western coast of Africa were other pink patches of the British Empire, with the largest being Nigeria, the Gold Coast, Sierra Leone and the strip of Gambia, a river colony some 20 miles wide and 200 miles long. Those countries were pretty much surrounded by the green colour of the French empire in Africa, the land of the Tuareg, the dessert, the river and the jungle.

And in the middle, the heart of darkness, the Belgian Congo, and one place he wanted to fly round, not even over.

If you draw a straight line from Johannesburg to London it takes you over the two Rhodesias then across the Belgian Congo, French Equatorial Africa, and French West Africa, skirting along the border of Libya, then under the thumb of the Italians and Hitler’s buddy, Mussolini.

That’s the way you would fly today, doing it in luxury flying at 40,000 feet in a jet doing 550 miles an hour. But it was not the way to do it if you were flying at a maximum altitude of 12,000 feet in a plane with top speed of 140 mph and a cruising speed of 110 mph. And a plane that had to be refueled every six or seven hours, maybe more often if you hit a head wind.

“You could never take the direct route. There probably wasn’t a petrol station from Katanga to Algiers. And there’s the Sahara to deal with. You could snake your way up the British part of central Africa, but no matter what you try you run into desert,” reckoned Marshall. “No, the only way to do it in a plane with a range of 1,000 miles tops, is to go along the eastern edge. You could almost make it landing only in British and Portuguese colonies.”

Then there was the weather. An amateur pilot like Bill Marshall would last a couple of minutes in a cloud, unless he had the willpower to look just at the artificial horizon and the altimeter. He could fly in a bit of drizzle, but if rained it was better for him be on the ground. A thunderstorm would rip the skin right off the Tiger Moth.

Then there were the people. Imagine the prospect of flying a Cessna 172 from South Africa to London. It has about the same range as the modified Tiger Moth and is only a bit faster. It does have a heater and closed in cockpit. Still, think of the places you have to touch down. Diamond wars in Angola, a vicious civil war in the Congo, the lawlessness of Nigeria and the hand choppers of Sierra Leone.

But, according to Bill Marshall, Africa was a different place back then.

“There was really not much to traveling across Africa in 1939,” remembers Marshall. “Almost the whole continent was run by Europeans. That meant it was pretty safe to touch down just about anywhere, though there were spots you might want to stay away from.”

Working in Africa he had a pretty good idea who treated the Africans well and who abused them. And those were the places to avoid: the Belgian Congo and French Africa.

It was a perfect day for flying, early September, 1939. Clear sky and full petrol tank and a wind that came off the ocean, lifting the tiny bi-plane into the sky after just 150 yards of runway. Once out over the ocean, and that didn’t take more than five minutes, Bill banked his aircraft and headed north.

He looked at the atlas in his lap and saw the purple colour of Angola, Portugal’s huge territory in eastern Africa. Its coastline ran for eight hundred miles from the edge of South West Africa to where the yellow strip of the giant Belgian Congo made its entrance to the sea.

About a hundred and fifty miles along the coast of Angola, he noticed there was a railway and some small towns. Places with names like Pedra Major, Pedra Minor and Mossamedes. The railway line told him there would be petrol there. But he didn’t want to spend the night there. Just pick up some petrol, to make sure he could take a one day run to Loanda, the capital of Angola.

The engine in the Tiger Moth made its constant drone. Bill looked down at the African coast and wondered how fast he could make it back to England. He had never thought of himself of patriotic, but for the past couple of years in South Africa he’d been reading the papers, and following Hitler’s slow progress across Europe.

It looked to Bill as if Hitler had the upper hand. He’d been reading a lot of what Churchill had been saying before the war and how Britain was unprepared. His father had been in the navy, but Bill wanted to fly.

“If this didn’t prove to them I was a pilot, I didn’t know what would.” he said of his flight around the edge of Africa. But he wasn’t home yet.

His trip though Angola went without any problem. He landed on a road near the of railway line, and there was a petrol station right there. It was a little before noon. He bought three bottles of cold beer, some bread and cold meat and got back in his plane. They took his British pounds, which he’d put in his pocket before landing. No use letting them know about the 14,000 odd pounds he had in his money belt.

Loanda was easy enough to spot. It too was on the coast, where a rail line brought the riches of the interior to the port. In this case the riches were coffee, cotton, sugar, diamonds, iron, and salt. For 300 years it was the place where the Portuguese mustered the salves they sent to their colony in South America, Brazil. It was a biggish city, and before he left South Africa Bill had checked whether it had an airport. It did.

What he didn’t like was what he saw in the northwest. A dark sky moving in quickly. The cloud was almost black and went in the anvil shape of a thunderstorm. Rain was hitting his face when he taxied to the end of the runway. There was an open hanger door and he taxied in without asking.

A man rushed over and yelled at him in Portuguese. Being a patient Englishman, Bill spoke to him in slow, deliberate English so that he could understand. He pointed to the sky and soon the man understood he wanted in out of the rain. When he passed him two five pound notes he seemed to understand more, and smiled.

Over the next hour or so Bill managed to negotiate a change of oil, a tune up and a place to leave his plane for the night. He also found the name of the best hotel in Luanda and had the man order him a taxi.

Loanda had none of the Puritanism of Walvis Bay or even Johannesburg for that matter. Bill Marshall recognized straight away for what it was, a Latin city, a Mediterranean culture plunked down on the edge of Africa. He felt right at home.

That night he cleaned up in the best hotel room he had ever seen. He was hungry, and tired of sandwiches. He went downstairs and had pretty much the same meal he’d had in Sydney five and half years ago. Prawns, steak and a half bottle of red wine. It was ten o’clock at night and the city seemed to be just starting.

Later he wandered into the hotel bar. Within half an hour he was back in his room with a woman who spoke a little English. She was from Lisbon, a little down on her luck and could use some British money if he could spare it. He went along with the game and she spent the night.

A twenty one year old has a mental alarm clock. He woke up around four, made love to his friend from Lisbon and let her sleep. He paid the bill and was at the airport by five thirty.

His friend at the hangar was happy to take another five pounds to push the plane out of the hangar. The timing was perfect and so was the weather, as the sun was a yellow ball behind him as he took off into the wind from the ocean.

The next part of his trip was iffy. There seemed to be no way he could make Nigeria, even if he flew in a straight line over the ocean, which he was reluctant to do. It was 900 miles, maybe a 1,000 until there was another pink spot on the map. There were two choices and he didn’t like either of them

The first was to drop down in French Equatorial Africa; the best looking spot was Libreville, though even that was 700 miles in a straight line from Loanda. He could try to make it the Spanish outpost of Rio Munti, but the Spanish were in league with the Germans, and as far as Bill knew might already be in on Hitler’s side in the war, as he was on Franco’s in the Spanish Civil War.

No, he’d take his chances with the French. They were England’s ally, if not every Englishman’s favourite country. He shouldn’t have worried about French Africa, at least not this part.

Libreville was once the capital of French Equatorial Africa and was a port on the Gabon estuary. It was easy enough to spot from the air. The French had built an airport there and Bill saw it from four thousand feet up. In his school boy French he ordered petrol, checked the oil and made sure the tube that had given him trouble earlier was free of dirt.

It a little after two o’clock. He was going to take a chance and make a run over open water. He had the compass bearings for Port Harcourt and he reckoned he could be there well before sundown, safe once again in the pink zone of Africa. As the coast came in sight, he looked at his watch and the sun. It was only three fifteen and he decided to press on for Lagos which he reckoned to be two hours away, three tops.

There was still some fuel left when he landed in Lagos, a little after six thirty. The sun was still up and would be for another 20 minutes. Lagos sat off a stretch of sea which his atlas identified as the slave coast. Lagos was hot and not the Mediterranean oasis that Loanda had been. He patted his money belt and found a place to sleep near the airfield.

In his room he looked at the map of Africa while drinking a warm beer. There he was at the bottom of big bulge and to go around the edge from here would take at least two extra days, as well as having to fly over a stretch of dessert. He decided on a more direct route.

The sun came up at twenty to seven and he could fly for 12 hours, but where could he get in twelve hours and where could he stop for fuel? The plan would be to fly from Lagos over the Gold Coast and head north in a straight line for Spanish Morocco. It would be an attempt at a record breaking day.

His plane was ready to go at 6:15. He took off into the semi-darkness, knowing there would be more light as he gained altitude. It was risky a manouever for an inexperienced pilot, but this was a day when he need the extra time.

Flying almost straight west he could keep the sea in view from four thousand feet. And after an hour in the air he had a change of plan. It was much too dicey to make a run across the desert. Always a chance of a clogged fuel line or oil leak. Better to keep the ports of west Africa in plain view, even if all he could see below him now was a carpet of green.

After five hours in the air he was thinking of dropping down for petrol so he could make a run from the Gold Coast to Sierra Leone. Ahead he spotted a port and cut back on the throttle and watched his altimeter as head headed down to land.

“Bonjour monsieur,” said a man who sat beside a hut that passed for a petrol station. Self taught navigation had its limits and Marshall found himself in the Ivory Coast, Cote d’Ivoire to the four black men he was talking to.

He hadn’t spoken a word of French since prep school, and he was more than a bit rusty.

“Le petrole s'il vous plait,” asked Bill in an accent that set the four men back. They looked at his plane and thought he must be a rich man, a playboy flying across Africa. They slipped into their own dialect and Bill started to get a bit nervous.

Just then a disheveled looking white man appeared from the hut. He looked like a character from a book Marshall had been reading just last week. Heart of Darkness. He almost felt he knew this Frenchman, or at least knew what he was up to.

“What are you doing here?” he said with a thick French accent.

“Flying from South Africa to London. Have to get back to help you chaps in the war. We’re in it together again,” said Marshall trying to charm the Frenchman. It didn’t look as if it were working. What did work was a wad of notes he had transferred from his money belt to his pocket.

Double the price for petrol. Some oil for the engine and water for Bill, along with some bread and cheese. The four black men stared at the skinny Englishman who was back in his plane. He revved the engine, spun round and they backed out of the way. They were surprised he was heading the wrong way, into the wind which was from the south.

The rest of the trip took him back into the pink, the stretches of the west African coast where they spoke English, or at least the British were in charge. He made the run from the Ivory Coast to Sierra Leone just before nightfall. A bleak place, he was stuck there by a storm which lasted until noon he next day.

Freetown. An awful backwater. Truly the white man’s grave. He found his way to the local colonial club where the planters and policemen were glad of his company. He seemed to know more about what was going on in the outside world than they did. Two of them men in the bar hadn’t even heard there was a war on.

“Sorry old man, but the papers are six weeks old once we get them up river. I thought Chamberlain was still talking to Hitler. Invaded Poland you say? Fancy that.”

Reminded Bill of a story he’d read by Somerset Maugham. The Outstation, where an old supreintendent opened his six week old copies of The Times one at a time. Once his assistant opened all the papers at once. The superintendent looked the other way when the man was murdered. All that time spent on ships had meant time to read and given him a literary education, if not a formal one.

Bill and his new friends got drunk as the rain showered the roof like machine gun bullets. There were rooms upstairs and he took one. When the sun came up he heard the rain and almost welcomed the delay.

The next day, two of them drove him to where his plane was parked. The men from the club had even posted a guard round it. One of their wives had packed him a picnic lunch and some beer. “She thought it jolly patriotic you were flying back to fight Hitler. I don’t expected they’ll ever show up here.”

“Maybe I’ll see you in London sometime,” lied Bill. Doubtful he’d ever see these men again. Doubtful he’d survive the war, if if it was anything like the last one. “Or maybe I’ll be back this way when it’s over. Thanks to your pretty wife for me. God Bless.”

It was a feast on the four hour flight to Gambia. Cold roast beef. Chutney. Even a light salad. The beers went down a treat. Three of them. After an hour he had a pee into the bottom of the plane. It always seemed to find its way out.

From three thousand feet he spotted an estuary, but this time he checked it on his map. The islands off the coast told him it was Portugese Guinea. He could use another night like the one he had in Loanda, but something told him this coast wasn’t as rich as southern Africa. Better to set down in the British Empire again.

Gambia would be hard to spot, the men had told him in the bar.

“Funniest little place. It’s about 20 miles wide and two hundred miles long. Surrounded by the French on all sides. If you were on a tourist trip, I’d suggest Dakar. The Paris of West Africa. Black men there dress like they’re on the Champs Élysées. Everything’s French. Bathurst isn’t much to speak of, but it’s British , of course.”

The men from Sierra Leone had used the wireless to tell the police in Gambia that a pilot named Bill Marshall was on his way. Flying home to fight the Hun. He was given quite a reception in Gambia. He decided not to get as drunk as the night before. The sky was clear and the desert was about to start.

This was the coast where the Harmattan wind blew, the one that took the cooled red sand of the Sahara and blew it out to sea. Bill knew about the wind, but he also knew he was a month or two early. Still, he would have liked to have seen it, even felt it as he flew along the coast of French West Africa, a thousand miles west of Timbuktu.

As his plane sailed low over the coast, he was at low enough altitude to look at the desert, he thought of Timbuktu, and how he’d loved to see a place like that. Mud hosues in the middle of a desert. He laughed out loud—he had no fear of talking to himself on the lonely stretches of his trip—laughing about the punch line to a joke he couldn’t remember.

“I bucked one and Tim bucked two.”

There were no jokes in the next spot. He had no choice but to land in a place where the English were the enemy.

The Spanish soldiers milled around his plane. One of them spoke English and started asking him questions, things such as whether he had been in Spain during the war.

“I was still wearing short pants,” said Bill with a laugh. He had told them he was a South African. They had no way of knowing he was English, since he showed them some identification from South Africa along with a plane with South African markings. “We fought the English too, you know. The Boer War.”

They nodded. Marshall poured on the charm and gave one of them, the English speaking one, a present of his picnic basket. It was warm out and decided to sleep beside his plane at the airfield. He put the petrol in just as night was falling and slept at the side of road across from a petrol station. There was no airfield, and few cars or trucks on the road.

As soon as there was hint of light he was into the air. One refueling stop in Casablanca, where there was an airport, and then the last couple of stops before home.

After leaving Casablanca, he decided against landing in metropolitan Spain on his way home. They might just confiscate his plane. Once again he would turn to the Portuguese, England’s oldest ally he had learnt as a boy.

He had been gone for six days now. He reckoned that he could make it home in two hops, one to northern Portugal, the other a run across to France with one refueling stop in a French town.

He did it, the last part of his trip being without incident. He planned to land near his home in Chichester. But somehow he miscalculated and came in over the Channel south of London. He remembers landing at Biggin Hill where the RAF took his plane and threw him off the base. He had hoped to join the air force right there.

“Instead I went home. I had been away for seven years. I walked into the kitchen and slapped my mother on the backside and said `How are you ma?’ For some reason she burst into tears.”

There were no recriminations. He sat down with his father and got drunk. A week or so later he went off to the join the Royal Air Force.