Who is Rich in Europe. Shocking Book Sale Numbers, a Roman Bikini and War is Over.

May 13, 2024 Volume 4 # 52

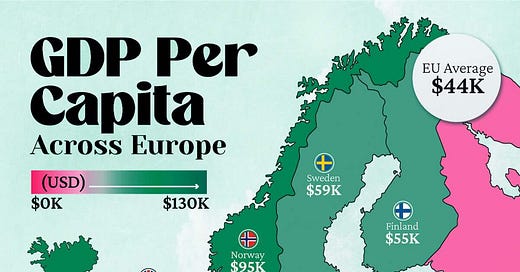

How Rich Are Europeans

After a long stay in Europe, I am back to `normal’. I am intrigued by how some countries in Europe are so much richer than others. Charts like this don’t tell the whole story of course. Cities in northern Italy like Turin, Milan and Modena are as rich as any in Europe. Almost all of Eastern Europe is still in post Soviet doldrums. The low per capita GDP in Russia, when measured against the Russian yacht class, shows what a bunch of thieves the so-called Oligarchs are.

Much of Europe is united in the European Union but per capita income— the size of the economy divided by the number of people— is not equal.

The richest are in tiny Luxembourg, home to much dodgy banking, followed by Ireland. The Irish number is suspicious. As a man with an Irish (EU) passport said to me on Saturday: “Not belieable. Once you get outside Dublin it can get pretty shabby.”

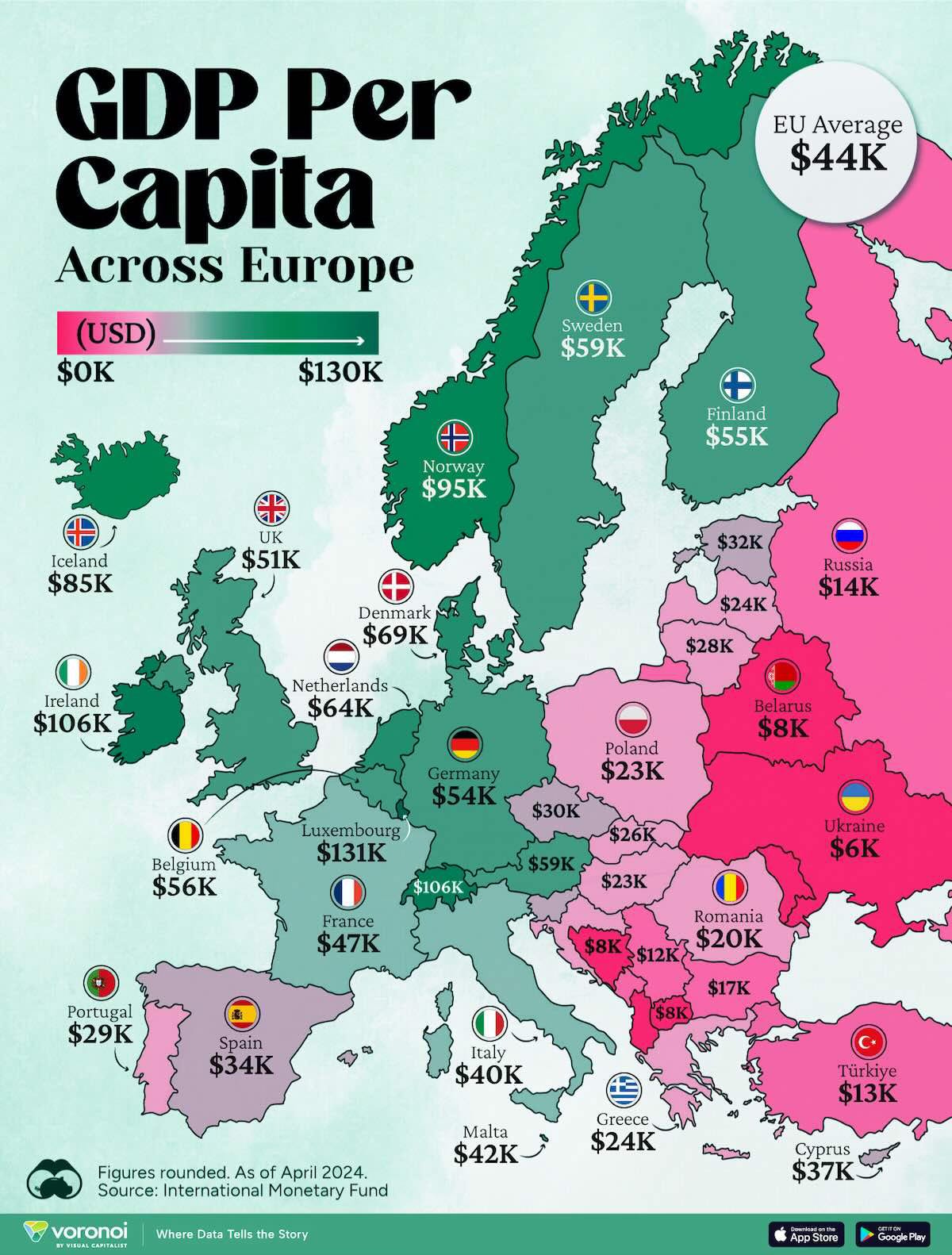

Asia is Nowhere Near as Rich

Only One European Country is Crypto Mad: Ukraine

You can make up your mind why some of these countries like the money launderers favourite currency. The better to make a portable getaway?

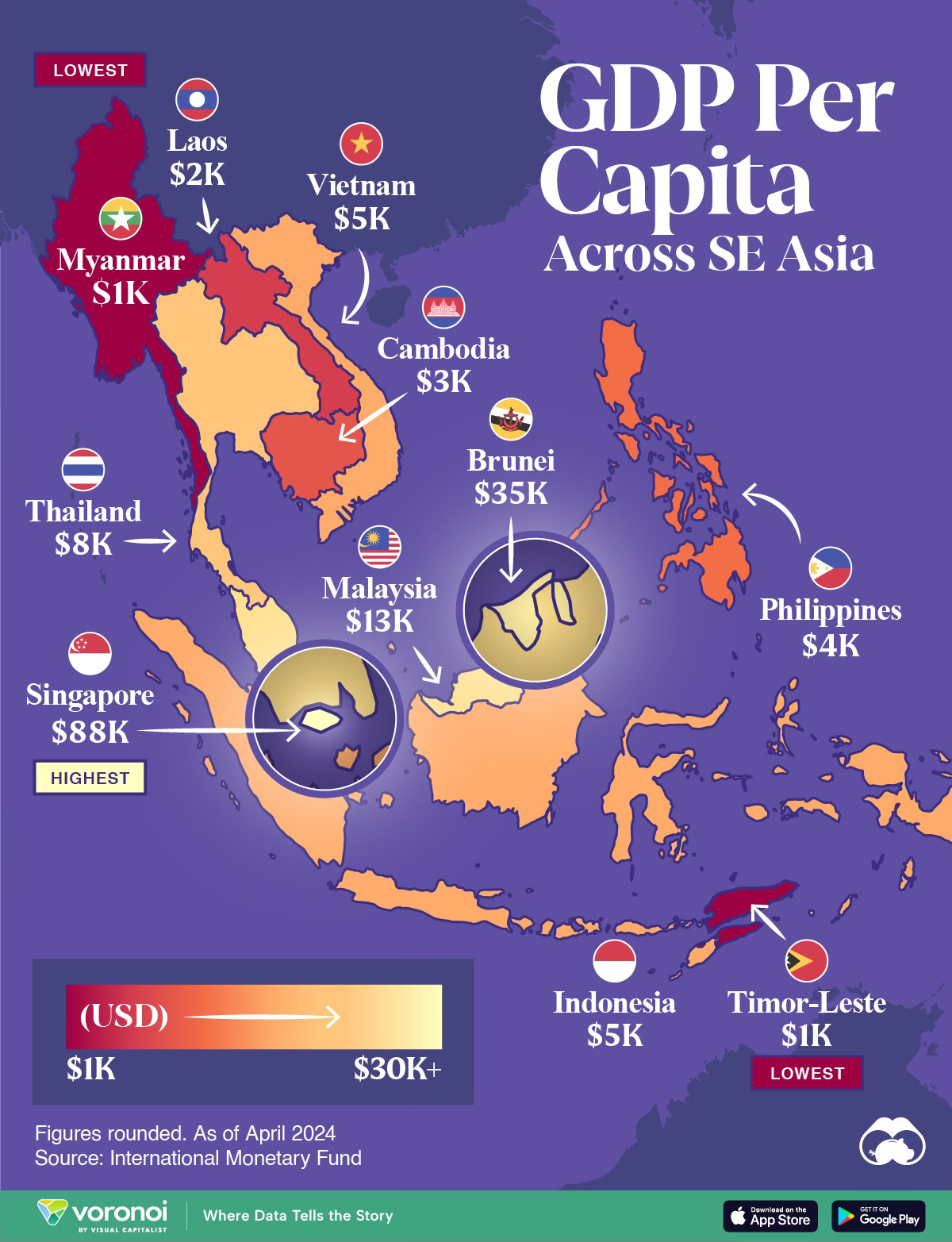

Money Doesn't Always Translate to Life Expectancy

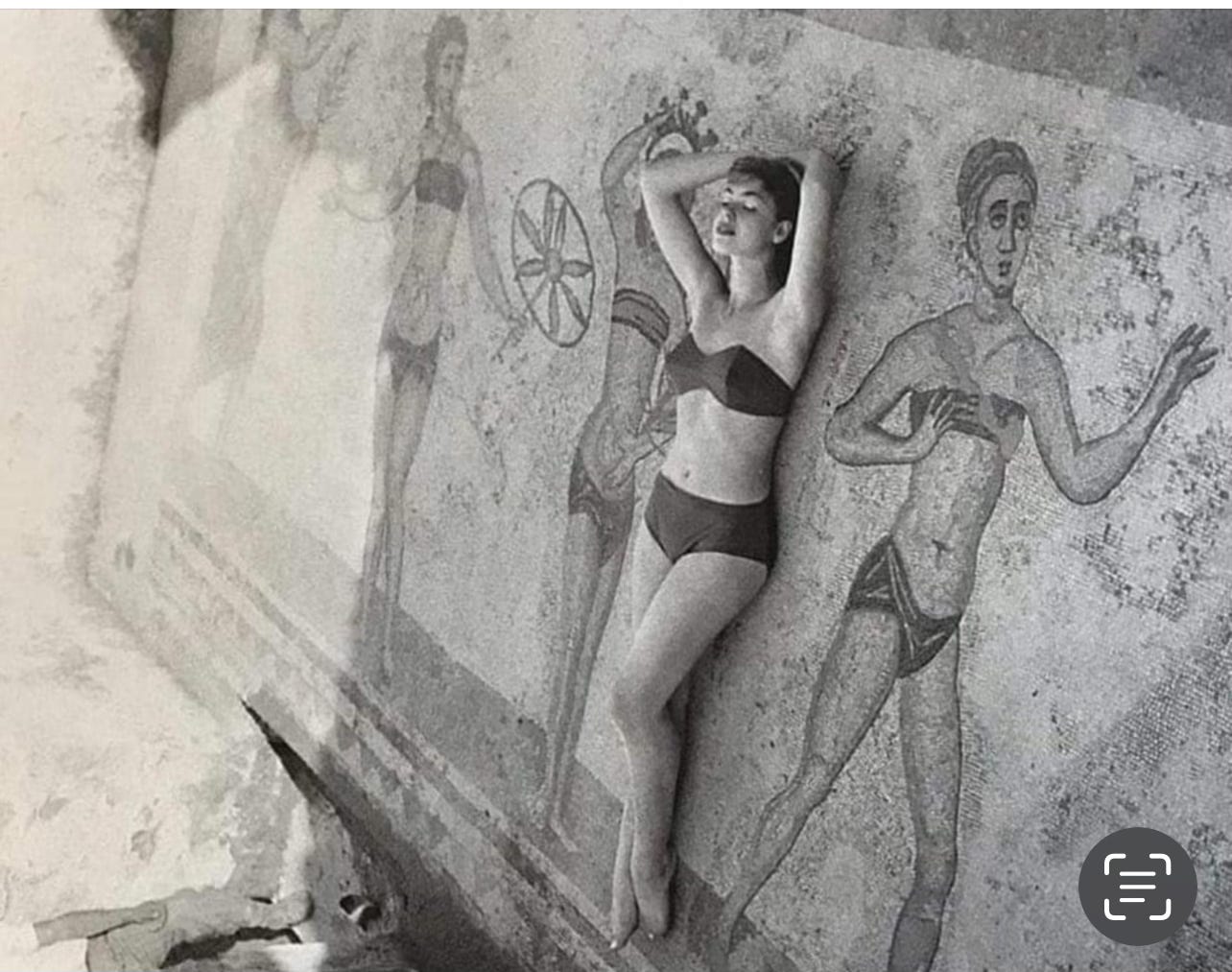

Roman Bikini

A 1956 ad by designer Emilio Pucci of his bikini on a model next to a Roman mosaic in the Villa Romana del Casale in Sicily. Similar scenes in Pompeii, sans Pucci.

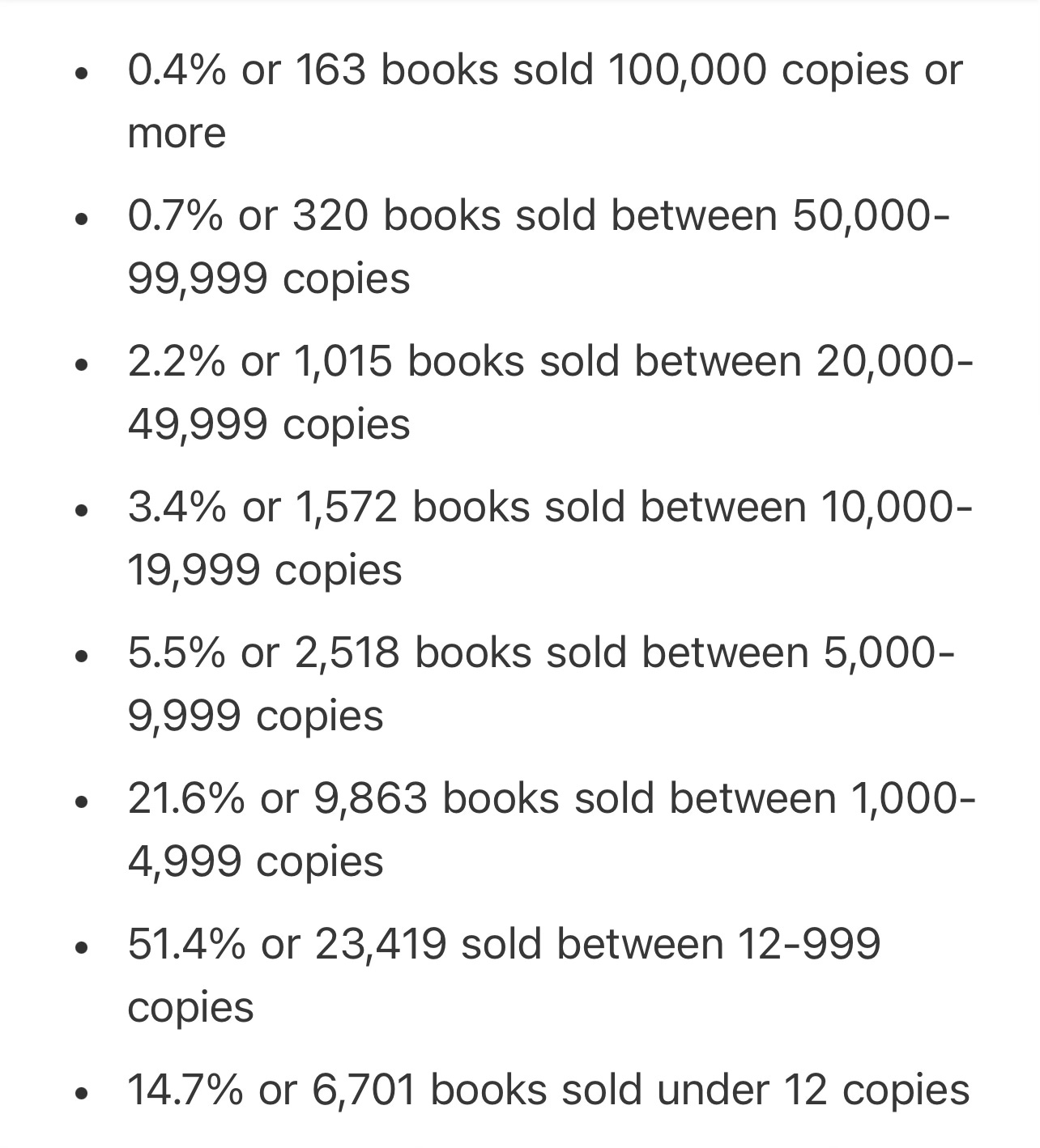

Book Sales

These numbers from SHUSH, the interesting weekly newletter by Kenneth Whyte, publisher of Sutherland House, show that most books have shocking sales numbers.

Whyte writes: “…numbers don’t include audiobooks or e-books, or sales outside the US. They are nevertheless staggering. Fifteen out of a hundred books published by the most expert, best capitalized publishers in America couldn’t manage to sell more than twelve copies. Do these authors not have families, friends, colleagues?

Worse, two-thirds of the books published by the most expert, best capitalized publishers in America sell less than 1,000 copies. We don’t have enough data to determine the average sale of a book in this less-than-1,000 category, but what would you guess? Two-thirds of books released by the best publishers in America sell an average of 600 copies? 700?

The Daily Telegraph used to list the number of books that were sold in the previous week in its best-seller list. I remember being bowled over by the statistic that one of Margaret Atwood’s books sold 22,000 copies in one week.

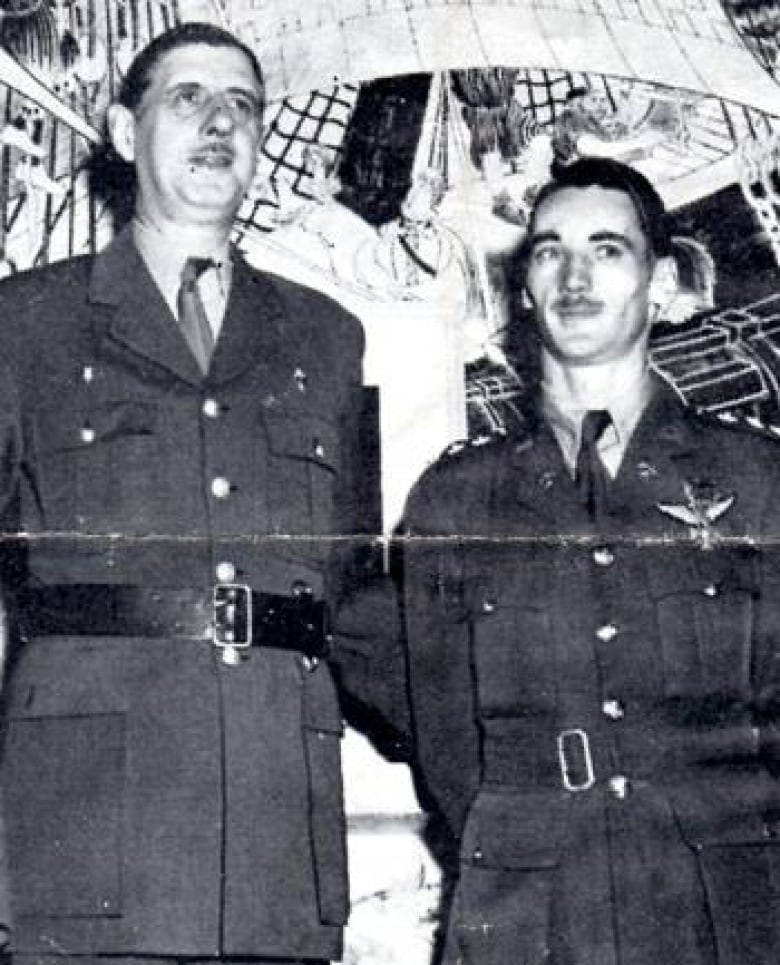

War is Over

Paris, the Champs Élysées, May 8, 1945

Essay of the Week

Speaking of France and war, this is a story I wrote for the CBC 14 years ago.

The kind of war hero about whom movies are made

Fred Langan · CBC News · Posted: May 06, 2010 2:56 PM EDT | Last Updated: May 7, 2010

Growing up, "the Major" was simply the father of a couple of close friends of mine, an affable, quiet-spoken man with whom I would play chess from time to time.

I didn't know until much later that Guy d'Artois was the type of war hero about whom movies are made.

It is a thought that comes back to me now every time we mark the end of the Second World War, particularly on its European front. His is a story not many people know.

During the run-up to the invasion of Normandy in June 1944, d'Artois and about 25 other French-speaking Canadians — almost all of them from Quebec — were dropped into France to wreak havoc.

They had been trained to blow up railway lines, assassinate German soldiers and lead the maquis, those disorganized bands of the French Resistance who needed not just weapons but instructions on how to use them.

D'Artois' group was part of the secretive Special Operations Executive, an undercover agency set up by British prime minister Winston Churchill with the objective, in his phrase, "to set Europe ablaze."

The SOE never achieved that somewhat romantic objective. The German grip on Europe was too strong and many SOE agents were captured, tortured and executed by the Gestapo.

One of those was Frank Pickersgill, brother of Jack Pickersgill, then secretary to Canada's war-time prime minister, Mackenzie King.

Send in the Van Doos

Almost all of the Canadian officers who parachuted into France during that period were from the Royal 22nd Regiment, known as the Van Doos. These were men whose native language was French and who could blend into everyday life in occupied France.

The SOE certainly had some successes, including the assassination in November 1942 of Reinhard Heydrich, the SS general in Prague who helped plan the extermination of Europe's Jews.

But there were also terrible reprisals for that assassination, including the liquidation of almost the entire village of Lidice in Czechoslovakia.

Guy d'Artois didn't know he would be part of the SOE when he joined the Canadian Army early in the war.

He volunteered for special commando training and was sent to a special base in Helena, Montana, which trained both Americans and Canadians in the darker arts of combat.

From Montana, d'Artois moved to Britain and a camp in Scotland where SOE agents learned what they were to do in France.

During a parachute training exercise, a beautiful young Englishwoman winked at him.

She was Sonya Butt, the 19-year-old daughter of a senior Royal Air Force officer. As she had been to school in France and was fluent in French, she volunteered for the SOE.

However, love at first sight for both of them created problems, which they compounded by getting married while they were still in Scotland.

That ruined the plan to drop them into France as a team where the last thing officers wanted was to have one person emotionally attached to another, in case of capture.

Eventually, both Butt and d'Artois were parachuted into France, but they were landed hundreds of kilometres away from each other.

Six months underground

D'Artois, then a captain, parachuted into the countryside near Lyon, deep inside occupied German territory.

For almost six months his task was to disrupt the German army by destroying bridges and rail lines, and attacking German military positions.

His troops were a ragtag group of patriotic French men and women, many of whom joined the resistance to avoid being shipped to Germany to work in its war factories.

The young French Canadian officer would later recount that they treated him like a general and followed his orders religiously.

He trained 600 members of the maquis as a combat unit and used other members to set up a secure telephone network behind German lines.

In one battle between the maquis and German troops, d'Artois reported that German soldiers used their rifle butts to club to death 33 wounded resistance fighters.

'Le Canadien'

In France, d'Artois was known to the resistance as Michel le Canadien.

Since he did not fight in uniform, capture would have meant being shot as a spy.

The Gestapo searched for the slight, French-Canadian officer, at one point sending an attractive blond collaborator to trap him. But she was found out and, in the end, she was the one shot as a spy by the resistance.

As for the French, "they were amazed that a French-Canadian would come back and help them," d'Artois said after the war.

His cover story included a platonic wife, a French agent named Annie who "shot a German officer down like that."

The sector around Lyon was not liberated until September 17, 1944, which was relatively late in the campaign.

France then awarded Guy d'Artois its highest military honour, the Croix de Guerre avec Palme, with the medal presented by Gen. Charles de Gaulle himself at a special ceremony in Canada in 1946.

His Canadian medals included the Distinguished Service Order, which, for a junior officer, was the highest medal for bravery below the Victoria Cross.

Our parents' war

While d'Artois was doing his bit around Lyon, his real wife, Butt, was operating as an SOE agent in the north of France.

At one point, she was captured by the Germans but escaped. The two reunited in Paris in late 1944 and returned to Canada where they would eventually have six children.

Guy d'Artois died in 1999. Sonya d'Artois, always known by her nickname Tony, is still alive and lives just outside of Montreal. At 85, she is one of the few survivors of the SOE and its operations in France but she refuses to give interviews.

Last summer I was at her 85th birthday, because two of her sons are close friends of mine. As a teenager I spent a lot of time at their house in Como.

When he died in 1999 I wrote his obituary for newspapers in England and Canada. Then I used his life story as the basis for a novel I published, The Obit Man.

My generation may be more obsessed with the Second World War than younger people today.

Most people my age have parents who served in the war. My father, for example, served overseas in the Royal Canadian Air Force in Bomber Command.

Growing up knowing people like Guy and Sonya d'Artois somehow makes the Second World War seem more real to me, even though I wasn't alive when it ended 65 years ago.